The McCartney Legacy Volume 2: 1974-1980

700-page book on McCartney is an astounding achievement

Allan Kozinn and Adrian Sinclair’s superlative examination of a post-Beatles Paul McCartney continues with a second volume that reveals Wings to be the ultimate lifestyle business

The McCartney Legacy Volume 2: 1974-1980 documents Paul McCartney’s life as he and Wings record the albums Venus and Mars (1975), Wings at the Speed of Sound (1976), London Town (1978) and Back to the Egg (1979). It also examines the sessions for ‘Mull of Kintyre’ (1977) and Paul’s solo album McCartney II (recorded in 1979 but released in 1980). There’s also focus on various side projects including Mike McCartney’s McGear album (1974), Denny Laine’s 1977 Buddy Holly tribute Holly Days (both of which Paul produced).

This is all done with exacting detail: every studio, every recording session, every mixing session. Perhaps casual fans may find these sections more exhausting than exacting, but after decades of McCartney biographies skimming over the nuts and bolts, it’s refreshing to see the dedication on show here. As a self-confessed McCartney nut, I learned an incredible amount. There’s also more to the book than simply documenting recording sessions. We also follow the McCartneys through their always busy lives and note when they go on holiday, when Paul gets together with John in New York, and which houses they are choosing to live in at any particular time, and so on. We also travel with the band and their entourage on tour in 1975, 1976 and 1979.

The book starts in early 1974, just after the release of Band on the Run. That album is very well received, by the critics, of course, and while McCartney never goes on to replicate this critical acclaim during the remainder of the 1970s (this volume ends in 1980 as Wings effectively to come an end), the combination of commercial and critical success undoubtedly puts a certain swagger Paul’s step and this second volume paints a clear and vivid picture of McCartney as someone who surrounds himself with enablers to help him to get what he wants.

After the intensity of The Beatles era, perhaps it shouldn’t be surprising that Paul was determined to have some fun in the 1970s. He remained driven: a workaholic, who effectively fused his personal life and working life into one big ball that steamrollered its way through the decade. And ‘work’ was what came naturally anyway; writing and recording songs.

The book confirms the suspicion that Paul is largely surrounded by ‘yes’ men whose job it is to react to his demands and make things happen.

Paul Sinclair

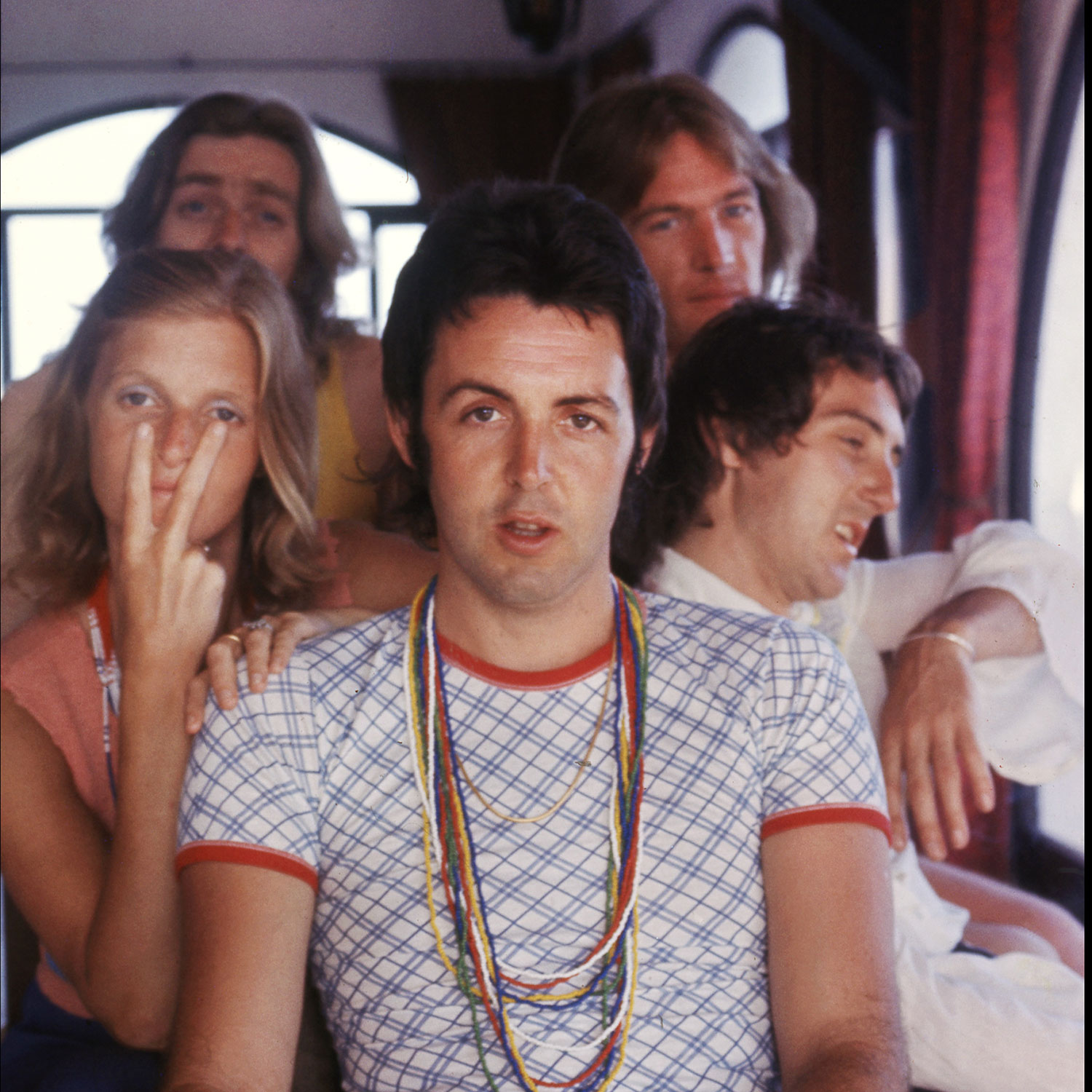

Paul wanted Linda in Wings, even though it seems pretty clear that she’d rather have been doing something else: either raising a family at home or perhaps pursuing her photographic career. So Linda and the kids follow Paul on tour (most notably on the Wings Over America trek of 1976) and wherever and whenever he decides to record. During the ‘70s Paul would regularly decamp to faraway places to make an album – including New York, Lagos, Morrocco, New Orleans, Nashville, and The Virgin Islands. These were basically working holidays and Paul admitted as much: “I like traveling and sightseeing, as does Linda, so we thought of combining sightseeing with work” he tells one reporter in New Orleans, in 1975.

One of the most interesting aspects of The McCartney Legacy is a view into the world of Paul McCartney’s support function; his backroom team who clear the path and make even the most fanciful of requests happen. Paul was incredibly fortunate to have Linda’s father, New York lawyer Lee Eastman, on his side to promote and protect his interests. Paul’s loyalty to Eastman both caused fractures in his relationship with the other three Beatles (who’d pledged loyalty to Allen Klein to manage the Fab Four’s affairs, in the late 60s) and helped clear up the mess afterwards (the legal wrangles went on deep into the 1970s). Eastman, with his son John, would go on to mastermind business deals for Paul during the decade and helped him build up his publishing empire (remarkably, on at least two occasions significant publishing catalogues were ‘gifted’ to Paul as a sweetener for signing new deals with record labels, including when he signed for Columbia in 1979). The importance of the Eastmans can’t be overstated.

Other players include Brian Brolly, managing director of MPL (McCartney Productions Limited) and Alan Crowder, Paul’s man on the ground who’d take care of virtually everything, including day-to-day logistics in terms of studio work and when the band were on tour.

The McCartney Legacy reminds us that members of Wings were effectively employees of MPL and across both volumes they appear to have the carrot of royalties and riches dangled in front of them only for that never to transpire. And while band members seem to have been reasonably well rewarded in later years, it was always based on an annual retainer and album/tour bonuses. They never had any skin in the game on any record, save for Denny Laine’s writing contributions, and when speaking to reporters Laine naively put a positive spin on his McCartney/Wings loose financial arrangements saying he liked the freedom.

Venus and Mars engineer Alan O’Duffy tells the book’s authors that Brian Brolly made it clear from the outset that there would be “no royalties” while pointing out that he would be joining the “McCartney family”. In the same vein, while in discussions over payment for the ill-fated Japanese tour of 1980, horn player Tony Dorsey tried to retrospectively negotiate a deal for the horn section that played on the 1976 tour, after the Wings Over America live album became a best-seller, proposing a 1 percent royalty to be split between the four horn players. Paul refuses, saying “you’re lucky to be working with me”.

It’s easy to forget how much the British press, in particular, hated Paul and Wings back in the day

Paul Sinclair

The book doesn’t do much to dispel Paul’s reputation for being tight with money when it comes to band members and fellow musicians, although this attitude seemingly never applies to other areas of Paul’s working life. For example, the post Wings Over America tour party in 1976 reputedly cost over £45,000 at the time, which is around £300,000 in today’s money and Paul surely spent (wasted?) a fortune in 1978 with his wacky idea to record some of the London Town album on a boat (the ‘Fair Carol’) in The Virgin Islands, because all the gear and kit had to be flow in with numerous technicians on hand (including Geoff Emerick) to install it.

Despite Paul’s claims of not having much cash in the early part of the 1970s (because it was tied up in Apple), it is abundantly clear in both Vols 1 and 2 of The McCartney Legacy that nothing is beyond the means of the ex-Beatle. He can charter planes, fly first class anywhere in the world (Jamaica being a favourite destination), buy land, buy houses, do anything. It’s hard to work out where his personal life stops, and his work life begins. Let’s not forget, in the early 1970s he was paying band members £200 a week and money (or lack of it) was the primary reason why first drummer Denny Seiwell departed on the eve of the trip to Lagos to record Band on the Run, in 1973.

Because the 1970s are now 50 years ago and Paul McCartney is regarded warmly these days by even his harshest of critics, it’s easy to forget how much the press, the British press in particular, hated – and there really is no other word – Paul and Wings back in the day. But The McCartney Legacy reminds us. In an era of Bowie, Floyd, Zeppelin, Roxy Music, and latterly punk, the reviews of Wings albums were largely mercilessly bad, with the notable exception of Band on the Run. But Paul never gives up. Every album, every tour, every gig is an opportunity to engage with the press which McCartney does regularly. But however much he charms them, by perhaps giving exclusive access to a recording session or allowing a member of the press to join the band on the leg of a certain tour, once a new album comes out, they are scathing, whether it’s in Melody Maker or the NME or publications such as Sounds. The glee with which they put the knife in is quite shocking by today’s standards.

Also, since many readers of this book may have come of age in a world where John Lennon had already been murdered, The McCartney Legacy reminds us just how unrelenting the press were with their “are The Beatles going to get back together?” line of questioning, in an era when all four members were still alive and it probably seemed inevitable that it would happen eventually. Paul is asked this question virtually every time he engages with a journalist. It must have been annoying, to be fair.

The book also confirms the suspicion that Paul is largely surrounded by ‘yes’ men whose job it is to react to his demands and make things happen. Should someone have the nerve to not say ‘yes’, Paul simply ignores them or shuts them out. For example, Aubrey ‘Po’ Powell from design studio Higpnosis, who was tasked with working on the artwork of 1978’s London Town, told Paul that the final cover with Paul, Linda and Denny Laine standing in front of Tower Bridge “wasn’t good enough”. Despite a longstanding relationship and apparently being a trusted part of ‘team McCartney’ (Higpnosis had created artwork for the previous four Wings albums and Po had been a photographer on the Wings Over America tour) Paul’s response, according to Po, was to say “I don’t care what you think, that’s what I’m doing”. In 1974 Po’s partner, the perhaps less pragmatic Storm Thorgerson, had walked off in a huff when the pair were tasked with setting up Paul’s idea for the cover of Venus and Mars (the red and yellow pool balls) “I don’t like that idea. It doesn’t work for me”, Storm tells Po. He never worked with McCartney again.

Another example involves the only time Paul hired a producer in this era: Chris Thomas, who co-produces 1979’s Back to the Egg. Getting sick of endless overdubbing sessions for the album, Thomas urges Paul leave things alone, and specifically not to overdub brass onto the song ‘Love Awake’. Paul ignores this, much to Thomas’ frustration. He tells the authors of The McCartney Legacy: “We screwed it into the ground, and it just got worse. The more we did to it, the worse it got… an amazing, beautiful song. It could have been much more simple”.

The authors of The McCartney Legacy choose not pass judgement on Paul’s decisions and actions. Along with their narrative, their analysis of the recordings and their many interviews with people who were there at the time (the source for every quote is noted at the back of the book) they leave it up to the reader to come to their own conclusions. However, while Kozinn and Sinclair are clearly McCartney enthusiasts (you’d have to be, to want to undertake such a mammoth project) you can occasionally detect a raised eyebrow or two in the tone of the text.

My thoughts, having now read both volumes of The McCartney Legacy are that once he was up and running with Wings (around the time of Red Rose Speedway and Band on the Run) Paul seemed to be determined to enjoy this decade and prioritised travelling around the world, being with his family and having fun. And he would write and record any song as the inspiration hit him, while doing this. His natural talent meant that hit singles were always around the corner, such as ‘Junior’s Farm’, ‘Listen to What The Man Said’, ‘Silly Love Songs’, ‘Let ‘Em In’, ‘With A Little Luck’, ‘Mull of Kintyre’ and ‘Goodnight Tonight’, but most of Wings’ albums – in fact if we’re honest, all of them in this 1974-1980 era – are mixed, uneven affairs. Paul either didn’t realise this or wasn’t bothered. And yet, The McCartney Legacy paints a picture of a man shocked and slightly depressed every time the next record gets bad reviews. The one exception had been Band on the Run in 1973, a record that would become an albatross – he couldn’t replicate that album’s quality or its cohesiveness and was apparently surprised when the significantly inferior Venus and Mars wasn’t reviewed with the same level of enthusiasm.

Paul has always, first and foremost, been a populist, driven by hits and success, and by that yardstick, he truly delivered during the era covered in Volume 2 of The McCartney Legacy. Band on the Run, the Wings Over America tour of 1976 and the British hit single ‘Mull of Kintyre’ (still the biggest selling non-charity single in UK chart history) were the peak of these achievements.

For Paul McCartney fans who have more than a passing interest in his period with Wings, The McCartney Legacy: Volume 2: 1974-1980 is nothing short of a dream publication. Along with the first volume, it’s a truly astounding achievement and I devoured its 700+ pages in a matter of days and was hungry for more by the end. The best book(s) you’ll ever read about Paul McCartney. Bring on Volume 3.

Compare prices and pre-order

Kozinn, Allan

The McCartney Legacy: Volume 2: 1974 – 80

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Reviews

Reviews

By Paul Sinclair

40