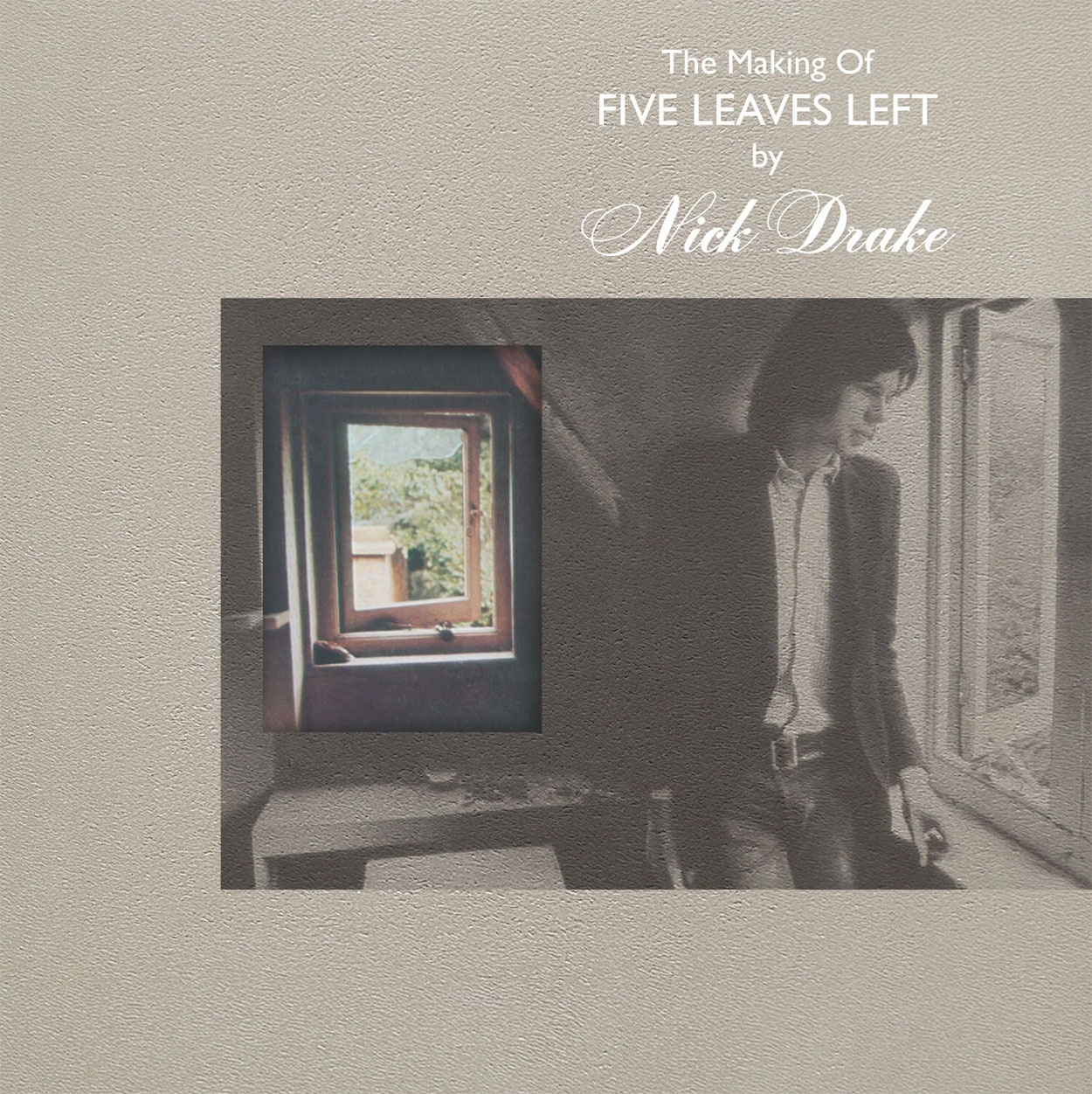

The Making of Five Leaves Left by Nick Drake – SDE review

The box set everyone’s talking about

“I’m afraid this is proving to be an unprofessional tape altogether, partly due to the intoxication.” It’s disarming, hearing Nick Drake speak this way. The mythic, fragile figure of English songwriting laughs to himself as he fumbles for chords, before playfully scatting, Mose Allison-style, over the introduction to ‘Mickey’s Tune’, a sweet, slight, bossa nova-indebted song. It’s incredible that it’s taken till now, and the release of The Making Of Fives Left, to hear this.

There isn’t a figure of Drake’s standing in post-war British music from whom we have heard so little. When Detectorists writer Mackenzie Crook repurposed Joan Gale Thomas’ 1924 exploration of faith and morals, If Jesus Came To My House, for his 2024 book If Nick Drake Came To My House, it felt apt. In the absence of interviews, live recordings or video footage, Drake has become an otherworldly figure. His music tends to be listened to alone, where deep personal connections are forged, and you can’t help but wonder about this enigmatic figure peering from the handful of surviving photographs of him. In his story, Crook wonders aloud how he’d react if Drake turned up on his doorstep, daydreams about how he’d take his tea, fantasises about playing him Elliott Smith or Radiohead, and – most of all – imagines letting him know how beloved his songs have become, how much his music has helped people. Tellingly, in Crook’s story, Drake barely speaks.

Since Drake’s tragic death on 25 November 1974, his archive has been fiercely protected. As his three albums – Five Leaves Left (1969), Bryter Layer (1971) and Pink Moon (1972) – found the audience they deserved, stray songs and sessions have inched their way into the light. The 1979 box set Fruit Tree saw the release of four songs recorded in February 1974; Time Of No Reply (1987) added a further 10 recordings made between 1967-69, all included in one iteration or another on Made To Love Magic (2004), which added Drake’s final recording, ‘Tow The Line’, from July 1974; A Treasury gave us the Pink Moon outtake ‘Plaisir d’amour’ (a short solo performance of the 1784 Jean-Paul-Égide Martini song which inspired ‘Can’t Help Falling In Love’); and 2009’s Family Tree was a 29-track set of home demos, including two songs by Drake’s mother Molly. Opportunities for anniversary editions of albums passed by quietly; lo-fi live recordings have been vetoed in the name of quality control.

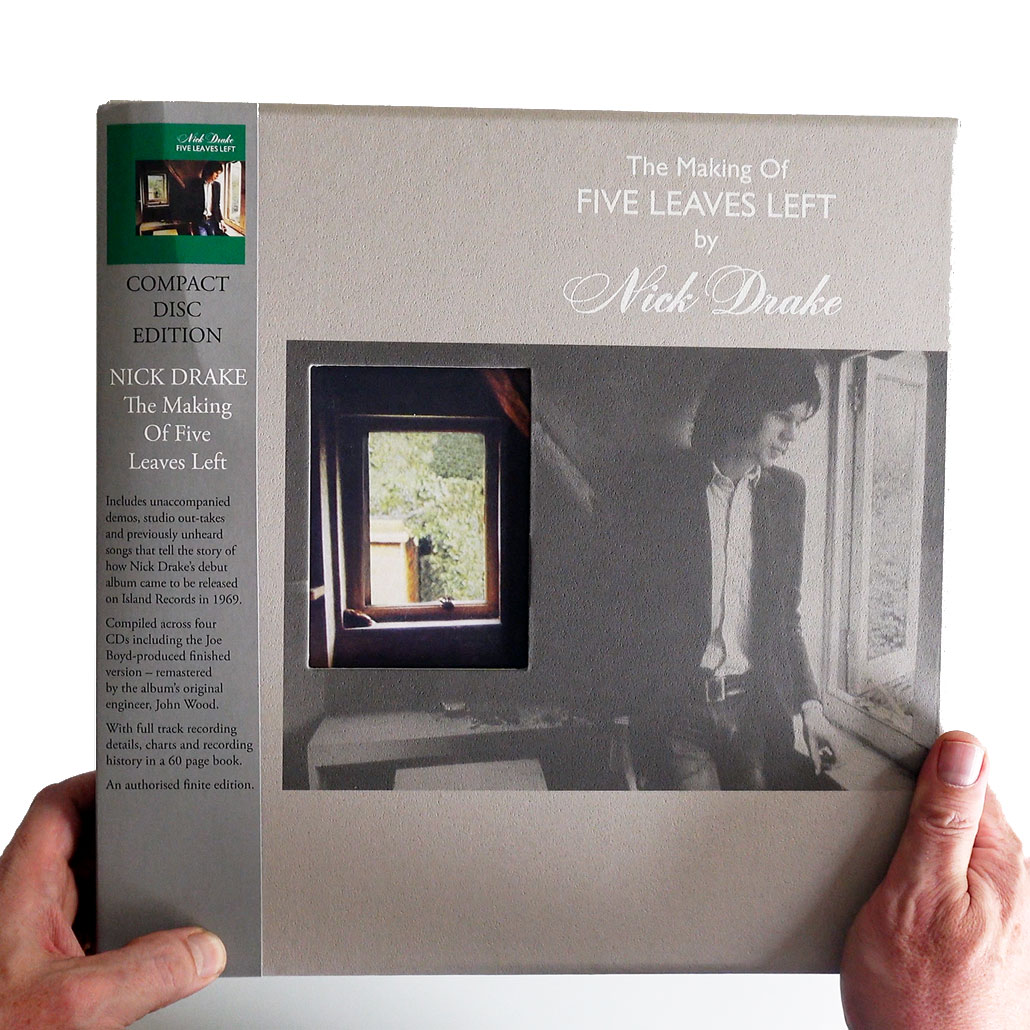

Which is all to say that the release of The Making of Five Leaves Left, a 42-track 4CD/4LP set featuring 32 previously unheard Drake performances dating from early 1968 to Spring 1969, is a significant event. This exquisitely presented set not only brings more of Drake’s music into the world, but it also allows for a deeper appreciation of his talent and ambition; those familiar photographs suddenly have that bit more depth.

So why now? In 2016, Drake’s estate began the search for Five Leaves Left session tapes. Almost all of the reels were found, and former Island Records head of press Neil Storey was assigned the task of painstakingly cataloguing the tapes. Over time, a cohesive story of the making of the album emerged. Still, the estate was reluctant to release every last second of the available sessions, as Storey writes in the sleevenotes, “as much as that might please the purist; it wouldn’t respect Nick”. When two revelatory tapes from the period came to light, the story of Five Leaves Left was ready to tell, from student demos to fully orchestrated splendor.

The earliest of these tapes was recorded in late January/early February 1968 by fellow student Paul de Rivaz on an early Grundig reel-to-reel recorder in arranger Robert Kirby’s Caius College room [Drake was a student at the University of Cambridge]. Things had moved fast for Drake. Back in December, he’d played his first ever gig, squeezed onto the bill of a charity concert organised by a friend at the Roundhouse, North London. Fairport Convention’s Ashley Hutchings was impressed enough by Drake’s performance to recommend him to producer Joe Boyd (Pink Floyd, The Incredible String Band), who had recently set up his own production company, Witchseason. When Boyd heard Drake’s demo (sadly lost to time), he was stunned and proposed they work together on an album for Witchseason. Drake’s search for an arranger led him to Robert Kirby, a music scholar who was also in the vocal group Fab Cab. Kirby later recalled Drake’s touchstones – Pet Sounds, The Fifth Dimension’s The Magic Garden, Tim Buckley’s ‘Morning Glory’, George Martin’s arrangements for The Beatles, Django Reinhardt. Kirby began working on arrangements using transcripts, but was keen to work from recordings of Drake’s songs.

The quality of the Beverly Martin recording is astonishing, offering a chance to hear familiar material performed up close and unadorned

SDE reviewer, Jamie Atkins

Which is where we came in. Seven songs from the de Rivaz tape are included here, capturing a relaxed Drake running through his repertoire for Kirby, often pausing to sing counter melodies or discuss ideas for arrangements. Anybody who has spent decades suspecting that the orchestration of Five Leaves Left was thrust upon a naïve Drake will be surprised – the tape shows he’s no shrinking violet, and has clearly worked out many of the parts in advance. “This was the one I wanted to get as expansive a sound as possible,” he says by way of an introduction to the elemental ballad ‘My Love Left With The Rain’ before suggesting flute lines and singing it through, breaking off at one point to admit, “I haven’t sung it for such a long time, I can’t remember the words”. Following a mellow take on the passing-of-the-season lament, ‘Blossom’, Drake repeats passages to clarify potential parts, self-effacing to the last (“it’s so corny but just a possibility”). He’s just as down-to-earth (“I cocked it up too, but y’know, you get the idea”) during a sketch of an unnamed instrumental with hints of ‘Dear Prudence’, though the ideas are pouring from him (“come to think of it, it’d be rather nice to have a solo violin”).

A mesmerising ‘Made To Love Magic’ is more revealing still, Drake preceding it by singing the flute part played by a friend, Micky Astor, at the Roundhouse gig and giving Kirby a steer on the transformative effect he wanted: “It would be nice to make this as sort of celestial as possible”. The tape reveals that Drake underestimated ‘The Thoughts Of Mary Jane’ at this point, suggesting he “probably wouldn’t do it, but just in case it works out nice from a backing point of view, it might be good” and drifting into instrumental passages. He sounds much more assured when it comes to ‘Day Is Done’, playing it solo and revealing he sees it as “generally a sort of string quartet song”. Finally, a delightful take on ‘Time Has Told Me’ has got a swing to it that’s pure Reinhardt – more evidence that, despite Drake’s music routinely being labelled ‘folk’, it’s a heady mix of cosmopolitan influences (cool modal jazz, Indian raga, traditional Moroccan music, chamber pop, US singer-songwriters, Impressionist classical composers) that suggests listening habits far beyond the Trad. Arr. crowd.

The following month, Drake recorded his first session for Joe Boyd in a professional studio, Sound Techniques, a converted dairy in Chelsea, London. He recorded nine tracks, the first six of which were copied onto tape for fellow Witchseason artist Beverley Martin, who kept it from harm’s way for decades. It’s easy to see why this session was chosen to open The Making Of Five Leaves Left; the quality of the recording is astonishing, offering a chance to hear familiar material performed up close and unadorned. Again, it challenges long-held notions, with Drake’s charisma and confidence shining through; his voice strong and sure, his playing impeccable. There’s a sense of a young man with the world at his feet, brimming with possibilities and aware of the strength of his material. This is the Drake who could mix it up with the fearsome John Martyn; the striking presence swooned over in anecdotes from eyewitnesses.

The jaunty social commentary ‘Mayfair’ is a pleasant enough start, but ‘Time Has Told Me’ is the real deal, the stripped-back arrangement revealing hitherto obscured jazzy guitar licks while Drake’s voice has a welcome grain to it. A subtle solo guitar take on ‘Man In A Shed’ follows, a world away from the business of the Five Leaves Left version. A sublime ‘Fruit Tree’ is one of the highlights of the entire set, Drake sounding spellbound by his performance, while a piano and voice take on ‘Saturday Sun’ stretches out with an aching nostalgia decades beyond his years – he was 19 here. Unbelievable.

The ‘Beverley’ tape concludes with ‘Strange Face’, a trancelike early take of ’Cello Song, after which the compilers fast forward to a version of the song recorded in September with Rocky Dzidzornu on congas and Remi Kabaka on shakers. It’s a neat trick, showing the evolution of the song in a relatively short time from solo acoustic number to a ravishing piece of esoterica, built on a solid groove and festooned with psychedelic flourishes – it’s unlike anything else Drake ever recorded.

The same approach is taken with ‘Day Is Done’, the compilers placing three takes spanning a year in succession. The first is from April 1968, the earliest sessions proper for Five Leaves Left, and features an arrangement by Richard Hewson (at this point, Boyd was unaware that Drake and Kirby had been working together) that makes for interesting listening but ultimately has a fussiness which sits strangely with the song’s resigned tone. A version recorded in November 1968, accompanied by the unmistakable, fluid bass of Pentangle’s Danny Thompson, is a gem, while the instrumental take from April 1968 showcases the genius of Kirby’s arrangement.

Sessions truly got underway in November 1968 with the arrival of Thompson. A take of ‘Time Has Told Me’ from the bassist’s first day of playing with Drake underlines their chemistry, Thompson’s lyrical lines weaving beautifully with Drake’s guitar. A version of ‘Fruit Tree’ from the following week is another stunner, with Thompson anchoring the song, giving it a gentle swing when necessary and leaving the space Drake’s vocal needs.

As recording progressed over the winter months, Drake introduced more new material, including a radiant solo acoustic take of ‘Time Of No Reply’, which features here, from December 1968. The following month, he recorded ‘River Man’ for the first time in the studio, the uncanny power of the song already fully formed. By way of comparison, the set closes with a version recorded in April 1969, featuring an alternative string arrangement to the familiar Five Leaves Left version, although both were arranged by Harry Robinson, a seasoned arranger brought in when Kirby struggled to find the heart of the song. Though it’s missing the stirring orchestral middle section of the Five Leaves Left take, it has a spectral majesty of its own.

The final disc of the set features the 2000 remaster of the original album; attempts to revisit the original analogue master tapes were abandoned when engineer John Wood realised the extent of their deterioration. Still, to hear Five Leaves Left after immersing oneself in these extraordinary performances is to hear it anew. Only now, our sense of Nick Drake as an artist and as a person is fuller; those old photographs somehow have more life. We all know the tragedy that brings the story to an end, but The Making Of Five Leaves Left gives us the chance to get to know the artist as a self-assured, laughing, slightly stoned and bashful young man on the cusp of greatness. It’s given us all that; it’s given him his voice.

Review by Jamie Atkins. The Making of Five Leaves Left is out now, except in the US where it will be released on 26 September.

Compare prices and pre-order

Nick Drake

The Making of Five Leaves Left - 4CD box

Compare prices and pre-order

Nick Drake

The Making of Five Leaves Left - 4LP vinyl box

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tracklisting

The Making of Five Leaves Left Nick Drake /

-

-

CD 1: 1st Sound Techniques Session aka The Beverley Martyn demo & Alt Takes from February 1968 to April 1969

- Mayfair – 1st Sound Techniques Session – March 1968

- Time Has Told Me – 1st Sound Techniques Session – March 1968

- Man In A Shed- 1st Sound Techniques Session – March 1968

- Fruit Tree – 1st Sound Techniques Session – March 1968

- Saturday Sun – 1st Sound Techniques Session – March 1968

- Strange Face – 1st Sound Techniques Session – March 1968

- Strange Face – Rough Mix with Guide Vocal – September 1968

- Day Is Done – Take 5 – April 1968

- Day Is Done – Take 2 – November 1968

- Day Is Done – Take 7 – April 1969

- Man In A Shed – Take 1 – May 1968

- My Love Left With The Rain – Cambridge, Lent Term 1968

-

CD 2: Paul de Rivas Reel – October 1968 / Out-Takes November 1968

- Blossom – Cambridge, Lent Term 1968

- Instrumental – Cambridge, Lent Term 1968

- Made To Love Magic – Cambridge, Lent Term 1968

- Mickey’s Tune – Cambridge, Lent Term 1968

- The Thoughts of Mary Jane – Cambridge, Lent Term 1968

- Day Is Done – Cambridge, Lent Term 1968

- Time Has Told Me – Cambridge, Lent Term 1968

- Three Hours – Take 2 – November 1968

- Time Has Told Me – Take 4 – November 1968

- Strange Face – Take 1 – November 1968

- Saturday Sun – Take 1 – November 1968

- Fruit Tree – Take 4 – November 1968

-

CD 3 Out-Takes from December 1968 to April 1969

- Time of No Reply – Take 3 into Take 4 – December 1968

- ‘Cello Song – Take 4 – January 1969

- Mayfair – Take 5 – January 1969

- River Man – Take 1 – January 1969

- Way To Blue – Cambridge – Winter 1968

- The Thoughts of Mary Jane – Take 2 – April 1969

- Saturday Sun – Take 1 into Take 2 – April 1969

- River Man – Take 2 – April 1969

-

CD 4: The Original Album – Released 3rd July 1969

- Time Has Told Me

- River Man

- Three Hours

- Way To Blue

- Day Is Done

- ‘Cello Song

- The Thoughts of Mary Jane

- Man In A Shed

- Fruit Tree

- Saturday Sun

-

CD 1: 1st Sound Techniques Session aka The Beverley Martyn demo & Alt Takes from February 1968 to April 1969

Reviews

Reviews

SDEtv

SDEtv

By Jamie Atkins

5