Saturday Deluxe / Why isn’t a music box set considered a luxury item?

Box sets will always struggle be perceived as greater than the sum of their parts, argues SDE editor Paul Sinclair.

A rainy January in London turns into a rainy February, and the Roxy Music box set is out. The super deluxe edition price of £130 has sparked great debate on SDE about music box sets and what represents good value. I have been mulling this over myself and after a rather protracted twitter debate yesterday (see this thread) I have come to the conclusion that the record labels are in trouble, because generally speaking, the target market for physical box sets considers them a value proposition and not an item of luxury.

I used the example of a designer clothes on twitter, as an example. Paul Smith sells T-shirts at £65. In my opinion that is much worse value than the Roxy Music box set at £135 but with Paul Smith you are buying into a brand, a lifestyle and that sort of item makes a statement. If you can afford to buy a £65 T-shirt, you are doing okay; it is a transaction that celebrates success. For whatever reason, that T-shirt doesn’t come under the same ‘value’ scrutiny of a music box set, like Roxy Music. A £65 T-shirt is likely to cost £10-£15 to manufacture (my wife is in fashion retail), so that equates to something like a 75% profit margin. To put that into context, if we estimate that the Roxy Music box set cost around £45 to produce, and applied those same margins to the music industry, the retail price for the box set would be £190. It’s unlikely that anyone would find that acceptable.

So why aren’t high end music box sets treated as a luxury product, like a Paul Smith T-shirt, a Rolex watch, a Range Rover Evoque, or a Smeg Fridge/Freezer? You wouldn’t go into John Lewis and look at a £1000 Smeg fridge and start getting the calculator out and exclaim “what a rip-off’ it probably only costs them £300 to make this!” but time and again that is the criticism on SDE of expensive box sets.

In December 2016 The Human League‘s A Very British Synthesizer Group 3CD+DVD set was released at around the £80 mark and the merits of the product were entirely lost by cries of “how much!?” Fans mentally stripped the set down to its component parts – four optical discs and a book – and it was branded a ‘cash grab’. People were assessing how much it would cost to make (probably £25) and there was no other intangible, like a lifestyle brand, to bridge the gap between low cost price and high retail price. The package wasn’t a considered a ‘naughty, but nice’ luxury. Instead, the audience felt insulted by the band, its management and the record label. In this game of pricing ‘chicken’ the label gave in and just four months later you could buy the set for HALF the original price. This kind of action makes physical music consumers even more resolute, when the next expensive product comes along. I’ve lost count of how many SDE readers have proclaimed that they will wait six months and buy the Roxy Music super deluxe set for £50.

The problem is that however groovy a box set might be, it sits on your shelf, only to be seen and played by you. Buying music is a rather singular activity. Most of us don’t even need to go into a shop now and have a conversation with someone. The CD or box set is delivered by the postman, you open it, you play it, you read the book/booklet and you add it to your collection. You don’t take it to a dinner party and enjoy seeing people glancing at it like you might do with a nice watch, or impress your mates at the golf club when you pull up in a new car. Owning a great box set doesn’t increase your standing in society. Your exquisite taste in music and the fact that you can afford some flashy looking box sets go largely unappreciated outside of the confines of your own home and family life (possibly inside your own home, too!).

Why will a casual fan pay £200 to go an see U2 live, while a diehard fan will think the same kind of money for the massive limited UBER deluxe edition of Achtung Baby is a ‘rip off’ – a blatant example of profiteering from the record company? On the face of it, that seems absurd, but everything comes back to intangible benefits and perception. Going to a big gig (‘the hottest ticket in town’) is a social activity and the experience is shared by friends – literally, these days, with ‘look-where-I-am’ social media. You are admired – you managed to get tickets in the first place! You are envied – you can afford to go! You can buy the T-shirt and wear it to the pub and go on about how “amazing” the evening was (even though you were in row Z of block 412 in the O2 and it took two hours to get home).

With that in mind, consider the following conversation:

“Did I tell you I bought this amazing box set of Roxy Music’s debut album the other day?”

“No..”

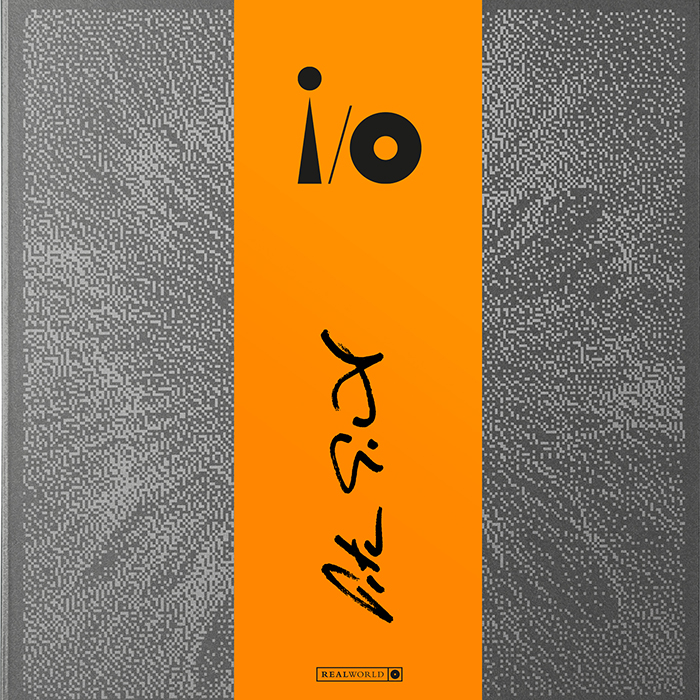

“It great. It includes loads of unreleased stuff, original demos… a 5.1 remix by Steven Wilson.”

“Who’s that?”

“Doesn’t matter.”

“How much did that set you back?”

“Er.. it wasn’t cheap. £130 actually.”

“What!? Are you mad? I don’t know why you bother buying box sets anyway. I listen to everything on Spotify. It’s free! You’ve got more money than sense”.

So, no kudos forthcoming for your investment or passion for physical music!

Music has got cheaper and cheaper over the years and decades. A new album on CD is £10, a deluxe edition, perhaps with some kind of bonus disc might be £10-£13. Physical music has never really been sold as a luxury item and therefore marketing super deluxe editions of one album into a £100+ product is no easy task. Unless the item is signed, or truly a limited item, people are going to want to see content to justify such price-tags. When you get into realms of £120, or £130 everything has to be PERFECT, or you could be in serious trouble. Paul McCartney‘s Flowers in the Dirt deluxe set committed the cardinal sin of being expensive (£130) and stingy (no 5.1 mix, a CD’s worth of audio via download only) and the new Roxy Music box doesn’t offer Steven Wilson’s stereo mix of the album, and misses out a B-side.

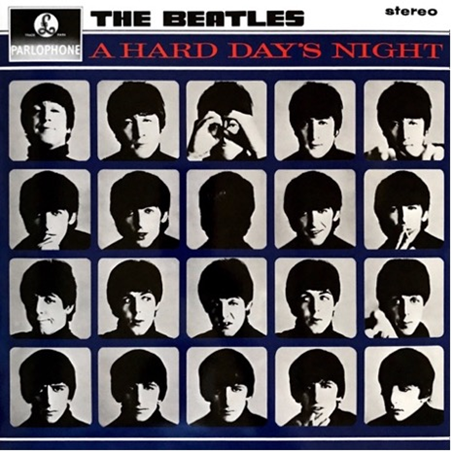

I have no doubt we will see more box sets in the next few years that push the barriers of what the consumer is willing to pay. At around £100, last year’s Sgt. Pepper box probably got the balance right between content and price, but it was The Beatles and it was a 50th anniversary. Most fans will think hard before investing a three figure sum on a physical music release, even if they don’t think quite as hard when it comes to spending the same money on a night out and a curry with their mates.

By Paul Sinclair

240