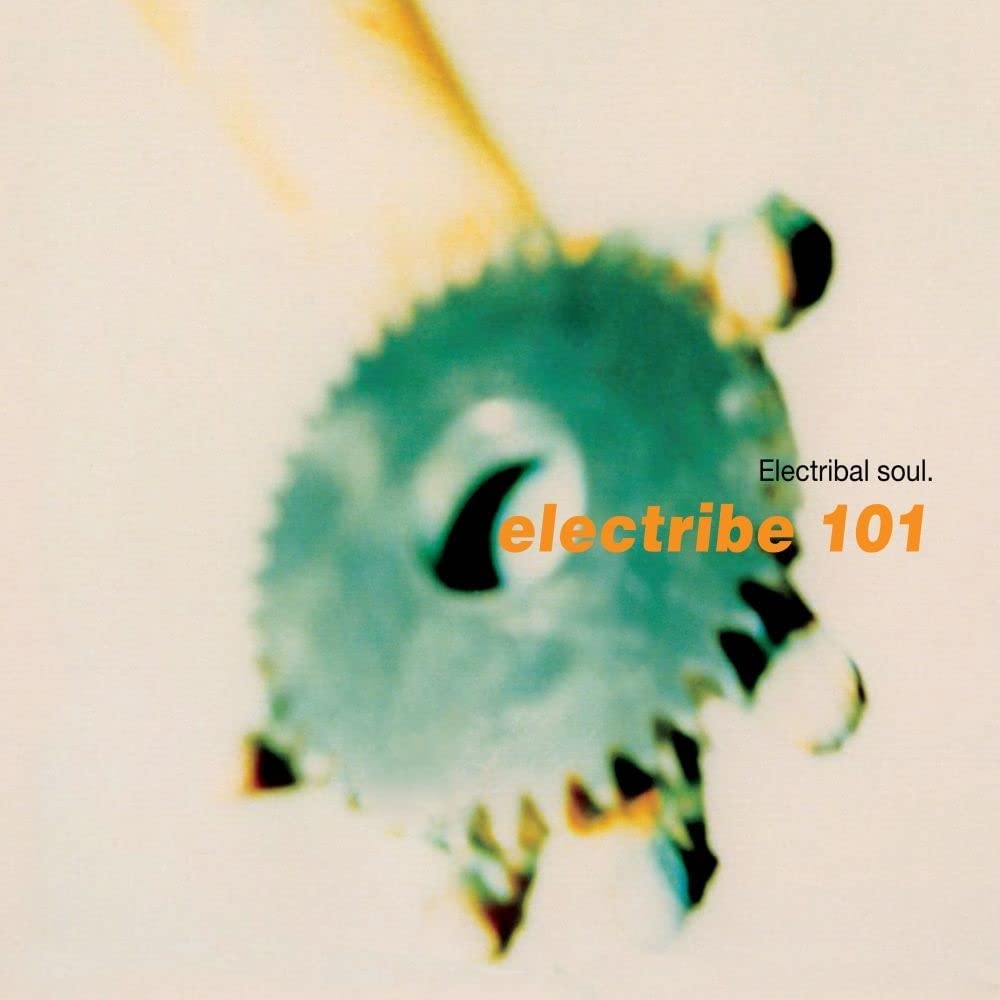

Electribe 101’s Billie Ray Martin on their ‘lost’ second album

“Working with Tom Watkins was horrible”

Electribe 101’s Billie Ray Martin on the 31-year wait to release the band’s second album and their complicated legacy

One of the most innovative bands to emerge from the rave scene, Electribe 101 formed when singer Billie Ray Martin placed an ad in Melody Maker stating “Soul rebel seeks musicians – genius only.” Having been on the lookout for a singer, Birmingham musicians Brian Nordhoff, Les Fleming, Rob Cimarosti and Joe Stevens were the required geniuses who helped shape Martin’s stunning and soulful multi-ranged vocals.

Managed by pop svengali Tom Watkins – who also helmed the early careers of Pet Shop Boys, Bros and East 17 – Electribe 101 scored hits with ‘Talking With Myself’ and ‘Tell Me When The Fever Ended’. However, as precursors of the Balaeric scene, the band were hard to pigeonhole. Years ahead of its time, debut album Electribal Memories stalled at number 26. Landing the support on Depeche Mode’s World Violation tour and opening for Erasure at Milton Keynes Bowl didn’t spark their commercial fortunes.

Watkins wasn’t used to managing such headstrong personalities, Phonogram lost interest and second album Electribal Soul was never even released. Although the band tried more record labels, they inevitably split in 1992. Martin enjoyed the dance anthem Your Loving Arms, but soon diversified into working with a huge range of styles and artists, while her former bandmates stayed together as The Groove Corporation. Cimarosti sadly passed away in 2019.

Over the years, that second album was talked about as a lost classic, but remained unreleased… until now. Issued on Martin’s own Electribal label, Electribal Soul really does deserve the “lost classic” tag, an album that hones the band’s dance dynamism and infuses it with a sleeker pop sensibility.

In a wide-ranging conversation with John Earls, Martin reveals how Electribe 101 could have stayed together, why working with Tom Watkins was “horrible”, plans for her four new albums… and why she’s pleased to finally have closure on her old band’s legacy.

Hi, Billie. It’s taken 31 years for Electribal Soul to be released. How does it feel to finally have it out in the world?

It’s cheered me up. Seeing the support the band has, it’s really made me smile. I hadn’t realised how big the support was for Electribe 101. I hadn’t listened to Electribal Soul once since we broke up. Everyone moved on, and the album just sat there.

Were you not aware the album had quietly gained status as a lost classic?

No, not at all. I’m so happy are people are saying to me “Did you realise how good it was?”, because at the time I had no idea. When we broke up, we didn’t think we had anything worth releasing, because that’s what people kept telling us.

If you hadn’t listened to it, what made you release the album yourself on your own label?

Well, I didn’t want to release it, as I was too busy making new music and I didn’t think I’d have the time. But the other option was to let someone else do it cheaply, so I thought I’d better do it, after all. It’s not going to be a huge seller, so it’s not worth another label taking it on. They certainly wouldn’t spend the time that’s needed to make it a good release. And I haven’t exactly been inundated with people saying they wanted to hear this second album. But someone has to put an end to our story, to put the legacy out there for people to hear. This album isn’t for everyone, as it’s a bit more pop. If people expect the second Electribe 101 house album, they might not find it.

How important was it for you to do a proper job on making it a worthwhile release?

I’m glad it’s been under my control, as it’s been a meticulous process. The audio has had to be restored, which was quite an undertaking, as I was working from a 30-year-old DAT. Then mastering was an issue. I initially had Grammy-winning mastering engineers, but I rejected everything they did: “No, I don’t care. Here’s your money. Next!” The funny thing is, I eventually asked Steve Honest, who I’ve worked with since back in the day. I could have gone to Steve in the first place. He has an ear for only tweaking where it needs it, not to do anything that makes the music sound different than what it already is. Then, Lewis Mulatero – who did the photos on Electribal Memories – sent me his old negatives over from New Zealand.

What was it like seeing those pictures after so long?

Oh, it was crazy. I had no memory we’d even done a photo session as a band with Lewis, as well as the abstract photos of his we used on the first album. There were hundreds of negatives, but they were damaged. So that was a process too, getting them scanned, printed, re-scanned, re-printed… I’m not perfect at spotting things that probably still need doing, but I’ve done my best and I doubt anyone else would have gone into so much detail.

Have you spoken to any of the rest of the band about the album coming out?

I spoke to Brian a year ago when I started planning the release. I told him: “Someone has to do this, so I’ll do it.” And that was as far as it went. I’ve not heard anything else from anyone else, but that’s fine. I’m glad Electribal Soul means I can speak about how positive I feel about what they did as musicians. I want to give them credit for what great musicians they are. Back then, making the album was just another day in the studio, when we weren’t sure about it. Now, I want to sing their praises, because they deserve it. I could have only made that music with that group of musicians, not anyone else.

When the album didn’t come out in 1991, how did you feel?

We were in such turmoil as a group, I don’t think we even thought about it that much. We didn’t think “Oh, what a shame”, because we probably thought it was rubbish. Now, I see that the songs are great. Back then, we were blacklisted by Phonogram, who eventually dropped us. The impression has grown over time that we walked away from the label. No. My recollection is that we were humiliated. We were told in no uncertain terms that we were rubbish. After we left Phonogram, we had a pattern of labels who said they wanted to sign us and then didn’t. It made us feel we were bad, rather than that we hadn’t found the right label. One A&R said he was considering signing us, but that he wanted to put us in the studio as a test. A test? We’d already passed the damn test. We’d shown we could produce good songs. That made us feel even worse. We felt we were no good, so it never occurred to us that people wanted to hear our music. That stayed with us, or certainly with me, for years. At the same time, Phonogram never capitalised on anything they had. There was no sync placement, no licencing, no reissues, no unreleased mixes, nothing. We were gone, just gone.

How do you feel now about the person you were when you made Electribal Soul?

What amazed me listening back to the album is that each song is what I was going through at the time. That made me quite emotional. I had the odd tear listening to Insatiable Love and A Sigh Won’t Do. There’s an urgency to the songs, because it’s all about me and I was belting it all out as intensely as I could. But I didn’t realise any of that at the time. It’s hard to believe now that you can write a song and think you’re making it all up, when it’s obviously about you. Thirty years later, you realise: “That was me, that was the relationship I was in.” At the start of Insatiable Love, I sing “She flies into the room, just in time for his call/It was time for a change.” That’s what I was doing at the time, but I thought I’d made it all up. To me, that’s amazing.

What was inspiring you musically at the time?

The UK was coming up with a few homegrown gospel and soul singers. I’d read Blues And Soul as much as NME, Melody Maker and Record Mirror. I was getting into all these ballads, much to the dismay of the record company. The rest of the band were fine with it. I’d show up with soul singles and say I wanted to write a song like this, and the guys would say “OK, cool.”

Hands Up And Amen is quite a dark song. What inspired that?

It’s fiction, imagining an older black woman getting mugged at gunpoint in Queens, which challenges her belief that she’s always protected, because God will fix anything. The “hands up” is both being held up at gunpoint, and also holding your hands up in prayer at church. The woman is trying to find the belief that it’ll turn out okay.

What about Moving Downtown? It’s on Electribal Soul, then your solo album Deadline For My Memories and, in the sleevenotes, you say some of the original lyrics were used in Pimps, Pushers And Prostitutes by S’Express when you worked with them. That’s quite the song history…

That’s right, even the Electribe version isn’t the original lyrics. The version on Electribal Soul is about how important it was to be played on Radio 1 and Capital. If they didn’t play you, you were a goner: out, no hit. It was weird when Radio 1 wouldn’t play our records, but would still talk about what I was supposedly up to. It’s about the people going to work at those stations and becoming part of the big machine. In some respects, Radio 1 was still fun, like being glued to it on Sundays for the chart countdown. For the version on my own album, I turned Moving Downtown into a relationship drama.

Speaking of S’Express, Mark Moore has said there’s a complete works S’Express boxset coming from Demon at some point. How do you look back on your time working with them on songs like Hey Music Lover?

Oh, that was so cool. It’s great if that’s coming out again. Mark and I are still friends to this day. How often does that happen? S’Express gave me a chance, and it shows how open the music business was back then. I met Mark at [Acid club] Shoom, when I went up to him and said: “I read in NME that anyone can join your group who’s mad enough. Well, I’m a singer, I’m mad enough and I’d like to join your group.” I gave him my number, he was really interested, so I joined this group of crazy, wonderful people. The chance that gave me was so exciting.

You cover Throbbing Gristle’s Persuasion on Electribal Soul and you later did another version of Persuasion as a single with Spooky. What’s so special about that song?

I listened to the industrial, experimental side of electronic music rather than the pop side, and Persuasion is just a song I grew up with. Everything about it is amazing: the meaning, the sound, the repetitive bass. It was so ahead of its time. I could hear myself singing those words, whereas with some songs I love, I think “Why would I sing that?” Emmylou Harris is my favourite artist and who I sing in the shower, but my voice doesn’t have the interesting quality for that kind of music.

What are you proudest of from your time with Electribe 101?

Firstly, what am I not proud of? What I’m not proud of is that we could have made at least one more album, if we’d stuck together and asked what was really pulling on us. We should have asked “Why are we pulling apart, when we should be growing together as people?” We had hostile intent towards each other, but that was because of external pressure, of being told we were no good. We felt abandoned and we didn’t deal with that. There was animosity, and I eventually said “I’m not cool with this anymore.” I’m not proud we didn’t put more trust in each other. It never occurred to me to ask “Why don’t we trust each other?” Every band that ever broke up will probably say the same thing. What am I proud of? I’m proud this album is coming out now and giving the legacy our group deserves.

How do you feel towards those other Electribe 101 musicians of 31 years ago, who are hearing the album now?

I’ve remembered the fun we had. We weren’t so happy as a group of people at that time, but I can hear the fun we had too. There are some mistakes we made when we’d fall about laughing. They were always playing pranks, joking and making fun of the lyrics. I can see now that there was all of that happening, as well as not knowing if we’d continue as a group.

What was it like to be managed by Tom Watkins? From the outside, having someone who was so pop seems a strange association for a band like Electribe 101.

It was horrible. It was horrible for me, and at some point it became horrible for the guys too. Tom just played games with people, trying to sack certain members from the band. At the beginning, it was me he tried to sack, and when it’s you he wants to sack, you didn’t know what was happening. He’d scheme and he’d threaten me. The band almost broke up. I was told he tried to do the same to Pet Shop Boys: he tried to sack Chris Lowe, telling Neil Tennant: “Chris doesn’t do anything, you don’t need him.” He did the same to me, to Bros, to all his groups. He was very destructive. When Electribe did our performance on Tonight With Jonathan Ross, I was suddenly okay, but then Tom started on the guys: “She’s alright after all, maybe it’s the guys we don’t need.” We got rid of him just in time. I could write a book about him.

Now that we’ve got Electribal Soul, could you reissue Electribal Memories too?

I tried for two years to get the rights back. Universal are sitting on it and are unwilling to be too communicative about it. The guy I was told to deal with wanted an advance and a good percentage of everything. They weren’t willing to talk beyond that, so I just gave up. That doesn’t mean it won’t happen one day, but Universal own the rights they’ve inherited from Phonogram, and it’s just how it works.

The vinyl version of Electribal Soul has three songs missing from the 11-track CD and digital version. Was it a consideration to produce a 2LP version to fit everything on?

It was easy to make the vinyl version, because you put the obvious songs on. The only songs missing are the short piece Conquering Tomorrow, and the two bonus tracks – the alternative mix of Deadline For My Memories and You And I (Keep Holding On). Doing a double vinyl wasn’t viable, because I have to think about how much I’m charging people. A couple of bonus tracks and maybe another demo, that’s not really a double vinyl. It’d be a rip-off, but it’s good to have a vinyl edition with the main songs on.

What about your solo catalogue? There’s never been a proper, concerted Billie Ray Martin reissue campaign, which is a shame.

Major labels sit on rights and aren’t helpful in getting things re-released. Or sometimes they give them to companies who wouldn’t do a great job, and I’m not having that. It has to be done right, but I don’t have time to release it. Again, never say never. I did speak to Warner about a Deadline For My Memories reissue, but they just weren’t creative. They said they’d like to hear my ideas, and that was cool. But once I said we could do this or that, they said “No, we don’t do any of that. We don’t get involved in creative things, we just give it to company XYZ to chuck it out there.” They didn’t want to hear a single one of my ideas after all, so it was “Oh, okay. Bye!” There is no music industry now, not in the sense of the way it used to exist. What exists now are three multinational corporations who are administrative bodies for streaming royalties and have a licence to sell products that might as well be Heinz Ketchup. That’s not a music industry. That’s not to say there aren’t good people working there, because there are, but they have no say in how the business is run, or who gets to release music. What I tell people is that we are the music industry: the multitude of independent artists who sell vinyl records and who play gigs. We make things happen, we can release the music and that’s a music industry.

Is it any better with digital distribution?

No. Electribal Soul is being handled by Believe Digital, who emailed all its artists a couple of weeks ago to say that, as of that day, they’re only pitching the top earners for playlist places on Spotify, Apple Music and the other streamers. All the streaming distributors have a limited amount of playlist places each month from the streamers. So of course they’re going to prioritise the artists who get millions of streams, who then get more streams from being on those playlists. It’s understandable that they don’t pitch Electribe 101. If Believe had pitched us and Apple or Spotify reject it, they’ve wasted their time, so I understand it. At the same time, it’s so sad they’ve decided not to give everyone a chance, especially when Believe state they help independent artists. On their website, it says: “We help independent artists navigate their way through the digital world.” No you don’t, you’ve screwed us all and then you refuse to talk to us.

Is that what is especially disappointing, that there’s no-one to talk to?

Well, it’s just a big faceless factory. I don’t know who Believe’s owner replies to, but his artists aren’t important enough. That attitude comes from the top: “We only pitch big earners,” and that’s it: done, no arguing. But I feel it’s all changing. I’m going to change distributors, and I was arguing with a friend who’s also on Believe to make a stand. I said that, if you only write one email, or post one tweet or Facebook message expressing your views that you’re not happy with Believe’s decision, it’s enough, because you’ve made your voice heard. It’s important to say your piece about the conditions artists are being met with. It’s about making the point that artists matter.

What’s next for you? Is it true you’re working on four new albums at once?

It is. The first two are almost at the same stage of being finished. I might finish them at the same time and I don’t know which will come out first. That’s cool, in a way.

Which one are you working on now?

The one I’m calling my French album. I’m not revealing its title yet, as I’m so excited about it. I’m working on arrangements with the Macedonian Philharmonic Orchestra for it. They’re well-known for their film music, and there’s an amazing video where they play Strings Of Life with Derrick May. I was almost in tears at the end of that video. They’re really hip to doing music outside of classical. They’re only on four songs and they’re not playing all over each song: I’m only putting them in strategic places.

What inspired the French album?

I’ve researched it since 2017. I wanted to make an album about how French popular culture has influenced me. Certain French movies and the history of Paris influence me every day. The album has four cover versions: two songs each by Charles Aznavour and Jacques Brel. I worried it’d be so boring if I copied what everyone else did with them. I sang so my versions of those songs into my iPhone notes, and at first I’d think “I’d rather hear Charles Aznavour sing this.” I knew I’d have to change the rhythms. From the mood boards I use for each album I make, I say to musicians: “Listen to this.” On this album, I’m working with members of Tindersticks, but I was referencing their own music, saying to them “You know that song you did there? That’s how I want to try this.” I made them listen to their own stuff, and it’s given us a framework from which we recorded straight away. Once we had that framework, my voice fitted in in a way it’s almost never fitted in on anything else. I guess I was singing from how I had thought in the back of my mind all along. I’ve also been really inspired by Kristina Barta, an amazing pianist from Prague. I’ve chosen a couple of really obvious Brel songs, as I grew up with them. I’ve researched the covers others have done, and nobody has done them the way I have.

Have you renamed Brel’s song Jacky as Billie?

No! I have done If You Go Away. I’d thought “Who needs another cover of that?” But all the artists who’ve covered it have either done it very straight or very “Ta-dah!”, hollering away. I didn’t want that, and instead it’s done as a strange, spooky film soundtrack. I was able to let rip, but in a very understated way.

Speaking of film soundtracks, your music has always been very visual, with strange characters peopling your songs.

Oh, always, yes. With all my songs, I physically see certain characters. I see the streets they’re on, that they look a certain way and it makes it easy for me to think “She walks around that corner and then she sees this guy.” I make up whole life stories for them. Songs are often inspired by actual movies, and some favourite films are always with me: Last Tango In Paris, The Tenant, Rosemary’s Baby… I read the scripts of those films, where there are rooms and descriptions not in the actual film, so I write a song about that room and who could be in it. Once I’ve written about a character, I’m done with them, but revisiting those movies rewires my brain. My characters are all misfits and hookers, and there are enough of them to go round. I research for months, watching documentaries and movies to get into character.

Do those type of characters go back to your childhood? You’ve spoken before about growing up in Hamburg’s red light district.

When I see a film with a new take on the type of characters I write about, I think “Wow, that links to what I grew up with and what I saw in my neighbourhood when I was little.” I grew up with all these incredible characters, but the new Hamburg has no place for them. They’ve already been gentrified away, or there are lost remnants I seek out. The homeless at least used to have a place to go, in the bars and social homes in that district. Now, what used to be private businesses are gigantic chains. But, on the side streets, people still try to support each other and I write about that, a then vs now scenario which also applies to Paris and the French album.

Is that style of writing common throughout your new albums?

Not quite. I’m about to continue work on Poems. Normally, lyrics and melodies arrive at the same time. But I was going through a loss in my life and I was sat helplessly every morning with my coffee. I thought “Hang on, I don’t have a melody,” but I just grabbed a pen and wrote down everything I was thinking as poems. I’d been reading Tennessee Williams’ poems, which were inspiring, as he wrote everything down without caring about the format, yet his poems are very accessible. I opened my notebook and these poems just happened, while I cried my heart out, because this was proper stuff from the soul. The tears on the page were from my loss. Once I had those poems, I thought “God, now I’m going to have to find someone who can produce this.” I thought it would be so complicated that I left it for a couple of years. Then I thought about doing it on piano and realised I could make it a lot simpler. Together with the engineer, we experimented with the sound we wanted, so it’s not just a boring piano album. And then I wrote the melodies all in one day. It all came in 20 minutes, from singing along to these poems. It was just crazy. While listening to some ambient shit, my instant melody writing worked. So now I had the lyrics and melodies.

Have you had obsessions you’ve wanted to write about, but haven’t found the right songs for?

No. Once I get an idea, it happens. 18 Carat Garbage was about me in America, going to Hollywood, Memphis and so on. Hollywood Under The Knife was about lost characters in modern America. Once something interests me, I find the right musicians to make it happen. With Hollywood Under The Knife, I found the amazing Robert Solheim and we became The Opiates. I’m exploring America again on another new album, which is about the alternative liberation movements and civil rights in the United States in the 60s and 70s.

Have you ever tried to just write a regular meaningless pop song?

I knew a couple of artists on the commercial side who were looking for songs. I tried to help them with that and I didn’t really enjoy it at all. It’s not that I couldn’t handle it, I just thought “Rather them than me.”

What’s the other album you’re working on?

Gezeitenraum, which came from Wolfgang Tillmans asking if I’d do vocals for his installation in Hamburg, which was in a concrete room with windows you can’t see out of, but where you can hear everyone outside. It also started with a German cover of Peter Gabriel’s Here Comes The Flood. This version has better lyrics than the original. It’s about how a great flood sweeps away mankind, but mankind is okay with that idea and is happy to be swept away. I thought “Yeah, that suits me fine.” Kristina Barta is on it, and some Belgian session musicians including the great drummer Dre Pallemaerts. For a long time, I was missing one song. I’d written a song about the first day in creating a new world. I’d thought “That’s too positive! I can’t sing anything about how the sun is rising.” Then I had the idea of merging destruction and rebuilding. That made it work.

Do you ever yearn for mainstream success?

My new albums will have a limited audience, but I’m 100,000 times happier than I’ve ever been. If my audience increases, hurray, but [so what] if it doesn’t? The people who listen to me really matter to me. I lost the idea of “Why aren’t I listened to by more people?” a long time ago. Once I dropped that, it was some major baggage gone. Over the years, I’ve dropped more expectations. I couldn’t give a shit if blogs write about me or not. Someone who’s really relevant with that attitude is Boy George. He feels the same way. He’s dumped the music industry and is happy to put videos and albums up on YouTube. He’s doing relevant stuff while being himself.

Electribe 101’s legacy is finally out there, you’re working on four new albums… are you in a good place?

I’m pretty overwhelmed with the workload. I have to navigate my health and be a bit careful. There’s too much going on every day. But at least I can concentrate on what I really want.

Thanks to Billie Ray Martin was talking to John Earls for SDE. Electribal Soul will be released on 18 March 2022.

Compare prices and pre-order

Electribe 101

Electribal Soul - vinyl LP

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Compare prices and pre-order

Electribe 101

Electribal Soul - CD

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tracklisting

Electribal Soul Electribe 101 / CD and/or vinyl reissue

-

-

- Insatiable Love 05:09

- Space Oasis 05:15

- Moving Downtown 07:48

- Conquering Tomorrow*

- Deadline for my Memories

- A Sigh won’t do

- True Moments of my World

- Hands up and Amen

- Persuasion

Bonus tracks

- Deadline for my Memories* (alternative version)

- You and I (Keep holding on)*

*Not on vinyl LP

-

Interview

Interview

By John Earls

23