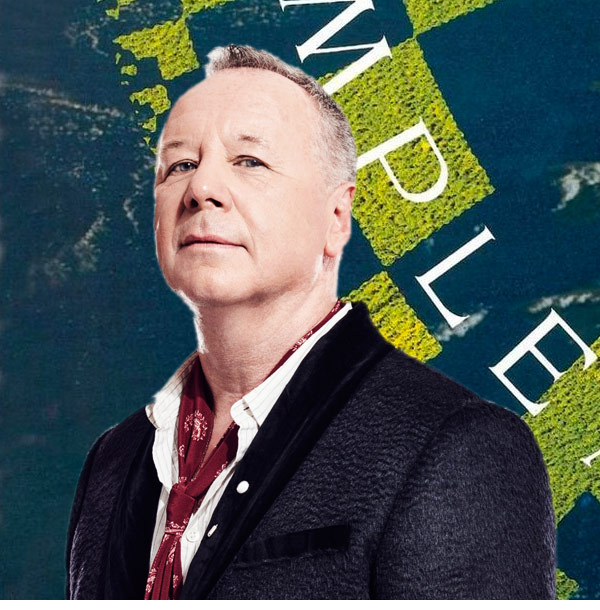

Jim Kerr talks to SDE about Simple Minds’ Street Fighting Years

With the super deluxe reissue imminent, SDE spoke to Simple Minds frontman Jim Kerr about the band’s 1989 album Street Fighting Years. “We sort of disappeared up our own arses, to tell you the truth…” he tells SDE editor, Paul Sinclair.

SDE: It had been a while since the previous album, ‘Once Upon a Time’. Did you have an idea in your mind as to how you wanted the next Simple Minds album to sound?

Jim Kerr: It’s funny, I mean, we didn’t realise it at the time, but by the end of Once Upon a Time and the subsequent tour that went with it – which stretched over a about a year and a half – I think we were dead on our feet. I think we really had come to the end of something.

We were so keen to get back home, not just for the sake of getting home, but waiting for us back home was this studio complex thing that we had bought, [and that we had been] building while we were away on tour and we were excited. It wasn’t so much that we were tired physically, although we were that, because from 1978 up until then, we’d never stopped.

And within that we’d also started to find good lives together outside of Simple Minds, and there was a lot of things needing attended to. So, we were dying to get back, but I also think we’d had it with what we were doing at that time. We were keen to see what the next thing would bring, and pretty much that’s my mentality as we began to work on what became the first few ideas for Street Fighting Years.

SDE: And you ended up working with Trevor Horn and Stephen Lipson. How did the choice of producer come about?

JK: Well, funnily enough, it came about because of the remarkable records he had made, they had made. They hadn’t really worked for many bands, although Trevor had worked with Yes, of course. We weren’t sure how that would work with us, but I think we felt that, unlike other producers who we’d worked with – and we’ve worked with some of the great ones – but we’d never looked to those previous ones to bring musicality to it, and we thought that Trevor and Stephen would bring a musicality and all their Fairlights and technology. Becoming bored with our own thing, we thought, well, we will strap our engine to that.

SDE: Did you have any concerns that they might take over too much and try and control what was going on? Because Trevor had a bit of a reputation for that, particularly with Frankie and all the rest of it.

JK: Ah come on, you can’t compare Simple Minds to Frankie! Give me a break [laughs]. We’re already six albums down the road and filling fucking stadiums… No, we didn’t have any problem with that.

SDE: I think they’d worked with Paul McCartney just before you; Trevor spoke to me about that. There were definitely some awkward moments with Macca.

JK: Whoever we worked with, and the people we worked with really beginning with John Leckie, Lillywhite, Jimmy Iovine, and then of course Trevor… I mean, there are lots of elements to these people and we were kind of in awe of them… we liked the pressure. I mean, Jimmy Iovine was the toughest cookie; he had a habit of both making you feel great and making you feel like shit, so you would try harder. And we wanted that, because all of them had made such great records. So, in terms of taking over… no, usually they all came at Simple Minds with such great enthusiasm that we had no need to feel that.

SDE: How much writing had been done prior to getting into the studio with Trevor and Steve. Did you have a bunch of songs or did you do quite a lot of writing in the studio?

JK: Well as I said, you know, because we had our own place [studio] by then, it wasn’t quite like before, when you would do your homework and get your stuff together and amass a load of ideas and go into the studio. So we had this place and at a certain point I think we felt we had a lot of ideas; some more fully formed than others. But [still] a lot of ideas and at that point we would say you know, we’re feeling good about getting a start here and to whoever we’re about to work with, here’s our progress to date. Very rarely did we have finished demos. But there would be titles, there would be choruses, there would be verses, there would be the atmospheres and it was like, okay, maybe producers would help us pinpoint missing pieces, if there were missing pieces. And indeed, how to turn all of that into a record.

SDE: You mentioned the studio, which was in the Highlands of Scotland. How much did the location influence your writing and the music?

JK: You know, in the last 10, 15 years I’ve written a lot of music. A lot of songs have been written in Italy where I’m sitting at a desk and I’m looking at Mount Etna, a volcano! [laughs]. But I don’t think you could hear that in the music. If you’re in a place where you feel good, where you feel energised [it’s good] but I think more of a point was that being there with no distractions, we were going to work Monday to Friday, and then we’d go home at the weekends, we would live there. So were immersed in it.

Funnily enough, thinking about all of that now, it sounds heavenly and it sounds blissful and I’m not sure that’s a great thing! [laughs]. Sometimes it’s good to step back, sometimes it’s good to be away, sometimes it’s good to have the clock going. At that time as well, technology came along. Up until then, our albums would have a maximum of, whatever, 48 tracks. Now you could have as many fucking tracks as you wanted. Well, that’s great [in theory], isn’t it? But you then have to develop a whole new talent around editing [the material]. And I think a lot of the weeks we sort of disappeared up our own arses, to tell you the truth.

SDE: Trevor Horn said that he was a little bit surprised that there wasn’t as much band-playing-live as he expected. It seemed like you were building things up in layers. Can you describe a little bit of the actual recording process?

JK: Well, I remember one thing… this was Michael MacNeil’s last album with the band. We didn’t foresee that, but I remember Charlie, everyone, started getting their own little home studio as well. So, Charlie would come in with an idea where not only was he playing guitar on it, but he was playing keyboards on it, because Charlie always played piano as well. And he would come in with something and it would be great. But it would be like, what’s the roles here? Who is doing what? You know, it was the start of all that bullshit as well. I didn’t care who wrote anything on what, I just cared that it sounded good.

There was new toys and I think some great stuff came out of some of those new toys. Charlie had been playing guitar for 10, 15 years and these new toys come along, he didn’t want to just do that [anymore]. He wanted to experiment and all that stuff, I mean, Mick did too, you know. You could program drums and they could sound great and you didn’t need a drummer sitting there all day. Usually, the drummer would get bored because he would be there for an hour or something, do his thing and then have to hang around until he was called on again. Everything was changing and I think a lot of good things came out of it, but you know, there’s always the stress of when things change. Certainly, it wasn’t, like all the albums we’d done up until then, where it was like “we’ve got five weeks, let’s do it.”

SDE: Obviously, it was the end of the 1980s and the album does evoke something to do with the end of an era. That seemed to inform your writing and your lyrics and the general vibe of what was going on.

JK: Yeah, I think, you know, that album… it’s all subjective, people’s memories of things, but in terms of music at the time, in terms of our generation, for many people I think the album embodies a kind of spirit at the time. Songs about the Poll Tax, obviously Belfast, human rights, all that stuff that… well, you know, they were the big themes. And I think, you know, if you’re going to be a writer and you’re going to write a lot of songs, I think it’s quite adventurous at some point to try and grapple with what’s meant to be the big themes.

You know, the Berlin Wall and all that stuff was on the verge of coming down. apartheid, a lot of that stuff, it came out in the music. Then there is personal stuff as well. I was beginning what became my divorce of my first marriage and there’s emotions there. A close friend had been murdered in Glasgow; all of this stuff was in there, from my point of view. Not obvious, I don’t think, but somehow there. To me, it’s obvious, but maybe not so obvious to anyone else.

SDE: Did you have any reticence about the overtly political nature of some of those songs? In terms of how it would be perceived by your fans?

JK: Yeah, I think we knew, you’re going to get in the neck. I think we were bright enough to know that for a lot of people once you step over what’s perceived as ‘your box’, that all this stuff of being… what would they say now, that you are ‘virtue signalling’ [laughs]. But you can only go with the music that’s in you, and the words that are in you, regardless of whether you’re writing a little pop ditty or whether you’re writing something about some tragedy in Northern Ireland; you can only go with what’s in you. You deal with the reaction later on.

SDE: Any concerns about the commerciality of what you were doing? As it turned out, ‘Belfast Child’ was a major success, but was the record company keeping an eye on you, worrying about big singles and all the rest of it.

JK: Well yeah, I mean particularly if you think the album, before it’d done so well in America. We knew, you know, they were pissed off at us because the thing is, success anywhere has to be celebrated and all that. But the success we got in America was great, but it was out of kilter with our success in the rest of the world, inasmuch as they were wanting us, six months later to be back in the studio and be back out with ‘Don’t You Forget About Me 2’. And you know, most people would’ve gone with that or tried to do that and certainly from a commercial point of view, that would’ve been the target. But what did we do? We headed for the hills for three fucking years and came back with a song about Northern Ireland, yeah, they weren’t too happy about that.

SDE: So how surprised were you when that first single, that EP, did so well and had such a positive reaction?

JK: Yeah, it was wonderful. I mean, you know, it was fantastic. I remember hearing it in the car and it was the least likely number one, or one of the least likely number ones. You know, the whole idea of a number one, well, what is it anyway? You know, what’s number one or number two? But it’s good.

SDE: ‘This is Your Land’ was the second single, and that has a memorable contribution from Lou Reed. Could you talk a little bit about how that came about and how you got Lou to contribute to the song?

JK: They all say that Trevor is childlike, in the best way. A child doesn’t feel limitations, and basically we had the song, and we liked it, but we had this middle bit and couldn’t find what to do with it. And really, somewhat pissing around during one take, I had done this kind of spoken Lou Reed thing, an imitation, and we just called it the ‘Lou Reed’ bit, and we were like, “yeah, we’ll get something for that…” And the weeks were going on and the months were going on and we hadn’t quite addressed it, and it always sounded really good when it came up. I actually thought it was more a Mark Knopfler kind of thing. But Mark Knopfler, Lou Reed; whatever. And finally, the clock was really on, we’ve got to finish this song, but what are we going to do? And it didn’t dawn on us for a minute that you could get Lou Reed; that Simple Minds could get Lou Reed to appear on a record. It just didn’t dawn on us that it would be possible. And also, I knew from someone really close to Lou Reed, that working with him could be a nightmare, according to them. And, so never in a million years did we think [it would work]. But Trevor was just like, “what do you mean? We’ll get Lou Reed.” And we were like, “fuck off, Lou Reed is never going to do this.” He said, “yeah, I think he will.”

So yeah, lo and behold, a few days later, Trevor got in touch with his management and he was like, “Yeah. He’s in Paris, he’ll do it tomorrow night.” So they looked at me and they said “you better to go over” with young Heff [Moraes] who was just sort of like a tape op. at the time. And I was like, “I can’t do that, I don’t know how to fucking do that.” It’s Lou Reed, to me it was like “get Picasso”. They said, “you’ll have to do it; go!”

So, I remember going over to the airport and when I landed in Paris I started having fucking palpitations. Because again, I’d spoke to my friend who had said, “he’s a nightmare.” Anyway, we book this little studio, set up the tape, put up the mic and just the magnitude of it to me… because I grew up with The Velvet Underground. I mean, they were really my band and Lou Reed was going to walk in the room. Talk about waiting for my man!

So right on the appointed time he turned up and he looked exactly as you would expect Lou Reed to look, and he gave me the limpest handshake I’ve ever had in my life. And he said, “so what is it, you know? What exactly is going here?” I said, “look, we just want you to talk over…” I said, “ignore the words, the words are just mumbo jumbo.” And he looked and he said, “the words are mumbo jumbo?” I said, yeah. He said, “I thought the words were beautiful.” And yeah, it was done and dusted in 20 minutes. And he couldn’t have been more gentle.

SDE: John Giblin’s work on the album was quite significant, wasn’t it? You know, in terms of writing and just overall contribution.

JK: Yeah. See, Giblin is one of my all-time favourite musicians. It’s a wee while ago now, but when Kate Bush played in Hammersmith [in 2014], I didn’t know John was in the band. I knew that he had played on her records through the years, but I hadn’t seen John for a while and I was delighted to see him up on stage.

I mean, John was only in our sphere for a couple of years because… I mean, John was older than us and although he was a Scot, he was older than us and we were probably a bit like brats compared to him. And he was such a fucking player and kind of a mysterious guy, but yeah, he didn’t particularly love Trevor. John and Trevor didn’t quite hit it off, I don’t think, and John didn’t quite like Trevor’s instructions.

SDE: What was that to do with specifically?

JK: I couldn’t tell you; I couldn’t tell you exactly why. Some people get on and then other people don’t, but John wasn’t in the studio much. You know, he did his thing then he left, he didn’t mind.

SDE: And what about Mel [Gaynor] then? Was it the same kind of situation. Potentially a bit awkward because you were using drum machines and this that and the other?

JK: Well, I think it wasn’t just with drummers. I think Trevor… how can I say this? Mel is so great at the ‘Mel thing’, but Trevor really tests you. I mean, he’ll go, “that’s great, got it – now give me something I’d never expect.” And I don’t think Trevor felt he was getting that from Mel, I think he felt he was getting the big thud the whole time, and it worked on some tracks, but maybe not on others. Yeah, I think Trevor felt that Simple Minds had done that so much on the previous records, certainly the previous couple of records maybe. That he wanted a lot more light and shade from the drums and that’s, you know, I can see the logic in that.

SDE: But that puts you in a bit of an awkward situation though, doesn’t it? That’s a bit tricky to deal with.

JK: Yeah, it does. But you have to… you can either be mature about these things or not [laughs]; you have to, that’s the way it is.

SDE: The flip side of that coin was the freedom to bring in some other guys like Stewart Copeland or Manu [Katché], how much did you enjoy that aspect of it?

JK: I mean, they’re great, great players, they’re great, great players. I’m not sure that… you are kind of caught between a rock and a hard place, because yeah, great, open the door and bring in other people, but it takes time to gel and sometimes there’s not enough time and so maybe you only get a flavour of what someone’s got, rather than the whole thing… but you know, we were huge fans of Copeland and I think I remember him talking more than playing [laughs] But it was great to listen to him!

SDE: You followed up this album with some new material on the ‘Amsterdam EP’ – namely ‘Sign O’ The Times’ and ‘Jerusalem’. What inspired those particular covers? And where did the enthusiasm to do some new material so soon come from?

JK: I think it was just one of those cases, you know, they were making that third single or something, and so therefore, you know…we need to get a B-side and that. So, we always tried to make a little bit more than, like a little event. And so, we tried some stuff, well more on tour I guess; we had a few days in Amsterdam, out of which came the stuff that you said and yeah, it was more like fun… and doing the unexpected.

SDE: With those tracks, and also with the following album, you were working with Stephen Lipson on his own. Was there ever any talk of getting the Trevor and Lipson back together? Or was Horn off doing something else?

JK: Well, they were having a little fracture between themselves by then. I mean, a bit like a band, they had worked together for the longest time and I think that was the start of them… I mean, they have worked together since, but it was the start of them doing stuff more on their own. I don’t think they did albums together after Simple Minds, both Lipson and Trevor Horn. Lipson did Annie Lennox and then that was such a big deal and he was off. But I mean, we saw Trevor last year and he was talking about Lipson and I’m glad to know that they’re still mates.

SDE: When this reissue was announced, there was there was some disappointment expressed that there were no unreleased demos that could offer an insight into the building blocks of the record. Was that something deliberate, where you just didn’t really want to open the sock drawer and get those demos out?

JK: Well, yeah, I saw that too. Some of the box sets we put out get a better reaction than others. It’s hard to explain, how can I say this without being patronising… I mean, just because you’ve put something on a piece of tape, it doesn’t mean to say that’s it’s a demo to go out. There was a few songs in the air there, but they were never part of Street Fighting Years, they were just something at the time. There’d be songs that Trevor wasn’t involved in or Steve wasn’t involved in… we were working every day. If you were to say every day equates to a demo for Street Fighting Years… no, it wasn’t, it was just that day’s work. And even the fact that people know about those tracks, means that someone nicked them and someone put them online!

Who knows? There’s a couple of those songs we might go back to – they’re unfinished. There are songs on our last album, Walk Between Worlds, from an idea that was more than 25 years old. Finally, we cracked it! So, the idea that you just load [the box set] all up with whatever was in the air at the time, I don’t think so.

SDE: I remember when the ‘Sparkle in the Rain’ reissue came out. Steven Wilson created a great 5.1 surround mix, and given the kind of widescreen, cinematic nature of ‘Street Fighting Years’, was there ever any discussions about maybe doing a surround mix of the record?

JK: Honestly, without putting the blame on anyone, it is our catalogue, but it’s not. If Universal [Music] want to invest in that stuff, they do, if they don’t, they don’t. I mean it’s theirs to do that stuff and sometimes they do it, as you say. What can we do? We can either sit and say, well, we want fuck all to do with this, this stuff. Or else we say, alright, if you’re going to do it, then let us get involved to whatever degree we can. But if they don’t see the logic in doing that just now, or have some vision of doing it at some point in the future, that’s up to them and they live with the consequences, I mean, we all do. But people either like it and want to buy it, or they don’t.

SDE: Most of the eighties Simple Minds albums are now reissued, but what about some of the earlier ones? Are there any plans to go back to ‘Empires and Dance’ and some of those early records?

JK: I would say again, that’s pretty much on the cards, all of it. Because again, the record company have a catalogue and these albums, certainly to a number of people, become iconic and stuff, and there’s always a feeling of wanting to bring stuff up to scratch. And to rework it or to remix it, or to whatever. So, if you’re asking if there’s any plans right now, is there a board with plans on it – no. But could I see that kind of thing happening, yes, probably.

SDE: Finally, all these years later, how do you look back on the ‘Street Fighting Years’ album and how do you, where do you rank it in the Simple Minds canon?

JK: It was a troubled record, it definitely was. It was the end of a period for us, we were still trying to figure out a lot of what was going on. Obviously, we did the tour. The tour was very enjoyable, because a lot of those songs worked so well live. But by the end, Mick decided he didn’t want to part of it anymore. And perhaps all of that stuff affects my feeling of it. But at the same time when I think of just the title and I think of the title song and it just sounds beautiful; very brave, I think a brave record. They’re all flawed, all of them. But yeah, it wasn’t the happiest time, but at the same time, I do remember a lot of great fun with Trevor and Steve and all of that. And as I said, hinted at, earlier, you can’t separate it out from what was going on at your life at the time. Not that I would want anyone to feel sorry for us, having number ones and playing stadiums [laughs] but, you know, not everything was well, and so when you look back on a record, it’s hard to separate it from all of that.

Whereas when I think of New Gold Dream, I just think, fuck… every day, it’s just amazing. These are the sort of, instant impressions, but, you know, we made this album, Street Fighting Years, it was a privilege to get the chance to make it and work with those people, and it’s a privilege that a fair amount of people took the music to heart and have embraced it.

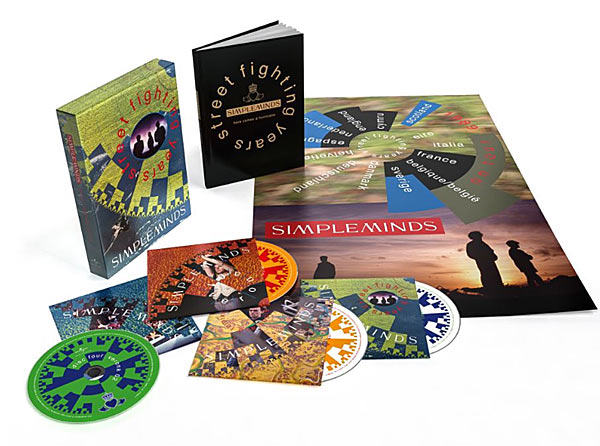

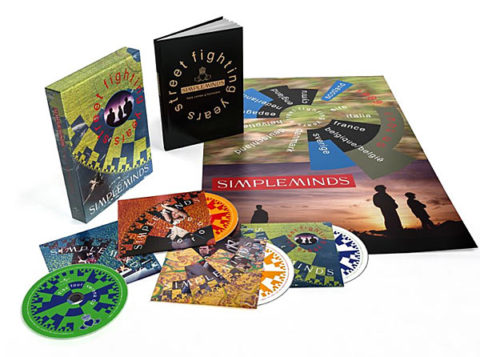

The super deluxe edition box set of Street Fighting Years is released on 6 March 2020. The box is down to £41 on Amazon in the UK.

Thanks to Jim Kerr, who was talking to Paul Sinclair for SDE.

Compare prices and pre-order

Simple Minds

Street Fighting Years - 4CD box set

Compare prices and pre-order

Simple Minds

Street Fighting Years - 2LP vinyl

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Compare prices and pre-order

Simple Minds

Street Fighting Years - 2CD deluxe

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![]()

Street Fighting Years – 4CD box set

CD 1 – Street Fighting Years remastered

- Street Fighting Years

- Soul Crying Out

- Wall Of Love

- This Is Your Land

- Take A Step Back

- Kick It In

- Let It All Come Down

- Mandela Day

- Belfast Child

- Biko

- When Spirits Rise

CD 2 – Edits, B-Sides and Remixes

- Belfast Child (edit)

- Mandela Day (edit)

- This Is Your Land (edit)

- Saturday Girl

- Year Of The Dragon

- This Is Your Land (DJ Version)

- Kick It In (edit)

- Waterfront (’89 remix)

- Big Sleep (live)

- Kick It In (Unauthorised Mix)

- Sign O’ The Times (edit)

- Let It All Come Down (edit)

- Sign O’ The Times

- Jerusalem

- Sign O’ The Times (C.J. Mackintosh Remix)

CD 3 – Verona part 1

- Theme For Great Cities ’90

- When Spirits Rise

- Street Fighting Years (live)

- Mandela Day (live)

- This Is Your Land (live)

- Soul Crying Out (live)

- Waterfront (live)

- Ghost Dancing (live)

- Book Of Brilliant Things (live)

- Don’t You (Forget About Me) (live)

CD 4 – Verona part 2

- Gaelic Melody (live)

- Kick It In (live)

- Let It All Come Down (live)

- Belfast Child (live)

- Sun City (live)

- Biko (live)

- Sanctify Yourself (live)

- East At Easter (live)

- Alive And Kicking (live)

Street Fighting Years – 2LP vinyl

SIDE ONE

1. Street Fighting Years

2. Soul Crying Out

3. Wall of Love

SIDE TWO

1. This Is Your Land

2. Take A Step Back

3. Kick It In

SIDE THREE

1. Let It All Come Down

2. Mandela Day

3. Belfast Child

SIDE FOUR

1. Biko

2. When Spirits Rise

Street Fighting Years – 2CD deluxe

CD 1 – Street Fighting Years remastered

- Street Fighting Years

- Soul Crying Out

- Wall Of Love

- This Is Your Land

- Take A Step Back

- Kick It In

- Let It All Come Down

- Mandela Day

- Belfast Child

- Biko

- When Spirits Rise

CD 2 – Edits, B-Sides and Remixes

- Belfast Child (edit)

- Mandela Day (edit)

- This Is Your Land (edit)

- Saturday Girl

- Year Of The Dragon

- This Is Your Land (DJ Version)

- Kick It In (edit)

- Waterfront (’89 remix)

- Big Sleep (live)

- Kick It In (Unauthorised Mix)

- Sign O’ The Times (edit)

- Let It All Come Down (edit)

- Sign O’ The Times

- Jerusalem

- Sign O’ The Times (C.J. Mackintosh Remix)

Interview

Interview

SDEtv

SDEtv

By Paul Sinclair

93