Thompson Twins: The SDE Interview

Tom Bailey and Alannah Currie talk to SDE about Into The Gap

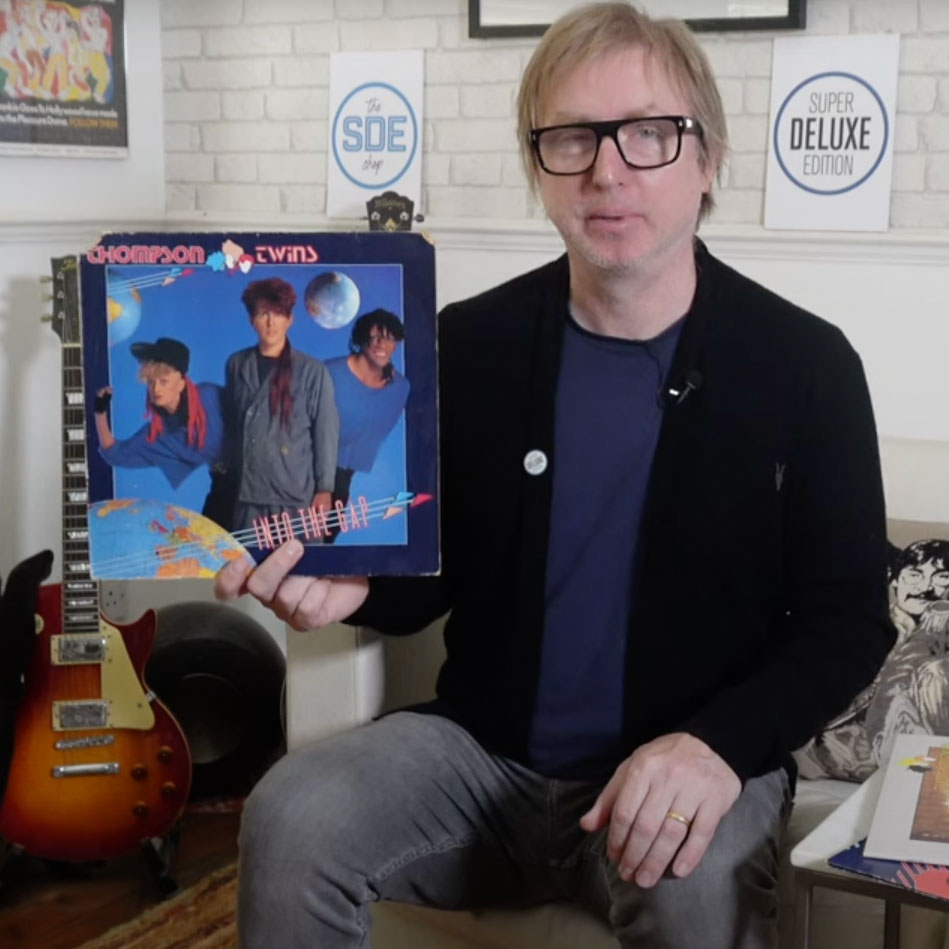

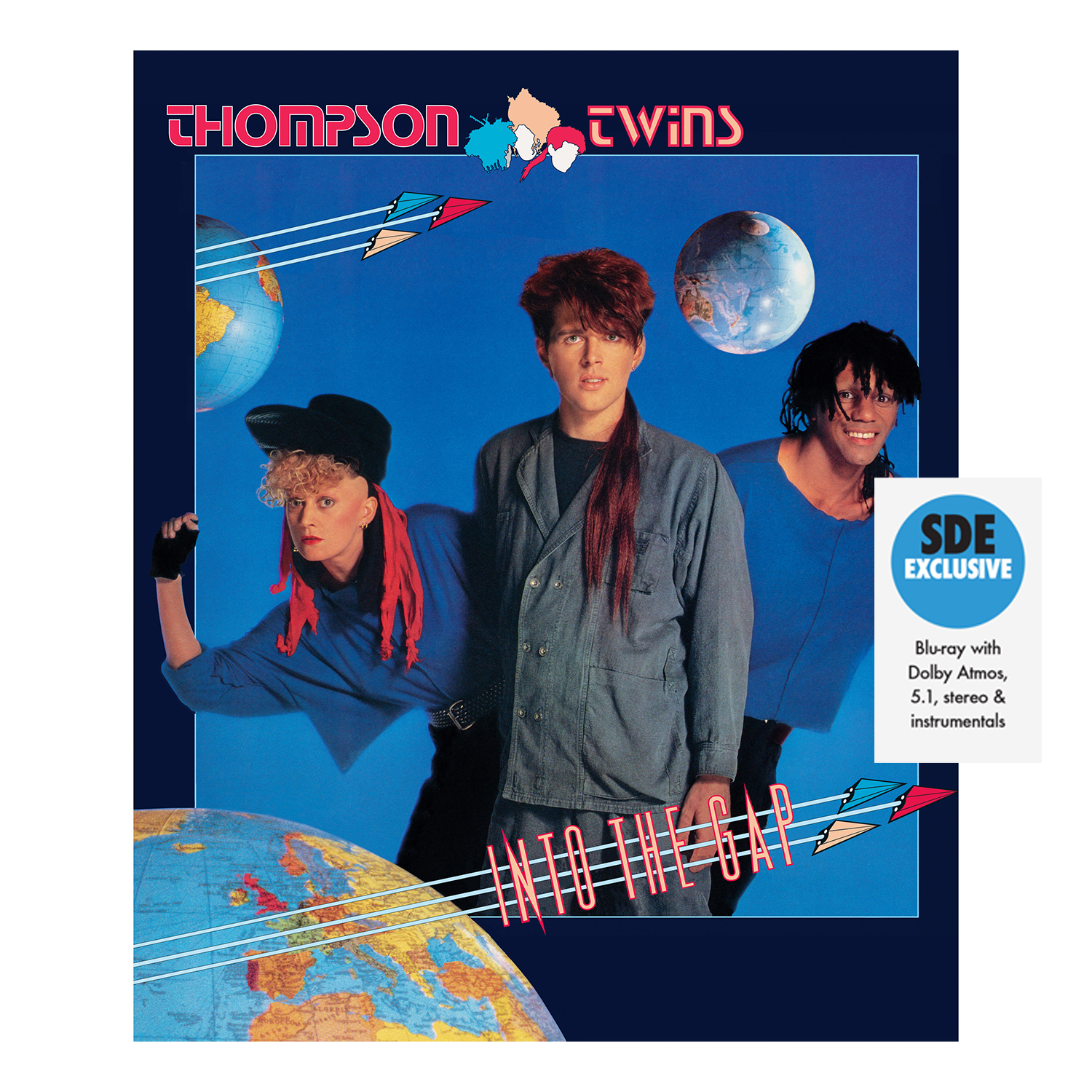

Late last year, BMG reissued the Thompson Twins‘ classic 1984 album, Into The Gap, as a 40th anniversary reissue as a 3CD set, on red vinyl and of course on SDE exclusive blu-ray audio. Last month, I caught up with Tom Bailey and Alannah Currie (separately) to discuss the album and the reissue. Between them they discuss working with producer Alex Sadkin, the fun (and pressure) of being a pop star in the early 1980s, life on the road, writing and recording the album and more…

SDE: What were your feelings when BMG approached you with regards to the Into The Gap reissue? I know in the past – I’m thinking of the Demon Music reissues in 2008 – that perhaps there’s been a bit of reluctance to engage. What’s changed all these years later?

Tom Bailey: I’m trying to think back to the Demon release, but we were not really active. We’re certainly not active as a band anymore. I hadn’t really got back into the live saddle at that stage [Tom only started playing Thompson Twins music again as a solo artist in 2014], so it was just something that was happening without our input, anyway. Record companies have always done that. I think there were several compilations, kind of greatest hits compilations, that we really had no say in – it just seemed like another one of those.

Alannah Currie: None of us got involved. We just let them [Demon] do whatever. Nothing to do with us. But for this [new reissue], we’ve talked to people. We’ve hauled out old photographs. We’ve helped them polish the jewels, really.

Tom: I think what happened was me getting back into playing live, and also the fuss about the 40th anniversary. Anticipating that, I tried to get this release out earlier in the year [2024], because I knew I was going on tour in America. That should have been a great moment to just promote the thing, but BMG, in their wisdom, were looking for a slot in their calendar where they could concentrate on doing a good job. That’s their call, they have to do what is right for them. But that’s what’s changed. Suddenly we’re in gear again, fighting for schedule synchronisation! [laughs]

SDE: 1984 always seemed like a classic year in pop music, where you had the likes of Duran Duran, Frankie Goes to Hollywood, Spandau Ballet, Culture Club and Wham! etc. and you were obviously a part of that. How did it feel to be in this movement that was happening. Did you feel part of that big surge of successful 80s pop bands?

Tom: I think so. Particularly with hindsight, there was a bit of a golden age thing going on there. At the time, it was very exciting, and it was great to have all that other stuff going on. There are golden ages in the 70s and 90s, so you can’t say that ours was the only one, but it started with The Human League’s early hits and ended, or partly ended with Frankie Goes to Hollywood, but definitely ended with Live Aid. That was the narrative arc of that golden age.

It was like the class of ’84, but we were the weirdos, we were the freaks

Alannah Currie

Alannah: We felt very much part of that scene. It was a bit like the class of ‘84, but we were the weirdos in the class. I think we were the freaks. We were slightly older than a lot of those others. We’d been round the block before. I think we were more political than a lot of them. We were into fashion and visuals and stuff, and we sort of had a vision of a new world, and we were sort of pushing to that. We were very much resisting writing love songs, or let’s-get-down-and-boogie songs, even though we love dance songs. I don’t know how much other bands were doing that. It’s very hard to look back now and judge where you were or how it worked. But we were definitely the freaks on the scene, but we really like being freaks. That was part of what we enjoyed about it – being slight outsiders.

SDE: This album, in particular, was the height of your commercial success. Did being a pop star match your expectations?

Tom: No. You can’t anticipate it or even understand it once it happened. But you can tolerate a certain amount of that as great fun. It’s like a party going on. And it’s interesting to discover that you become recognisable. Maybe I’m giving myself too much credit, but you have to keep these kind of things in some kind of perspective and once celebrity becomes more important than content, you’ve lost what you were doing. I think you can see that all around you at the moment. I’m so aware of a lot of people for how famous they are, but I’ve no idea what they actually do. That’s not entirely their fault, because that’s the way they’re marketed but it’s also the way that the scene has become fragmented. I don’t have time to listen to all of these famous young stars at the moment. However, back in the day, we’re talking in the early 80s, it was still the era of Top of the Pops, where everybody watched the same thing, and therefore the entire nation was aware of who the Thompson Twins were.

Once celebrity becomes more important than content, you’ve lost what you were doing

Tom Bailey

Alannah: It was shocking to get famous and to have that level of attention and enormity. And for a while it was really great fun. And I think the fun sort of ended after the Into The Gap album. Everything went downhill after that. So Into The Gap was the height of our fun days, if you like. When it was smaller, when you were still in contact with your friends, and it was still easy to come and go from your old life. That was a lot of fun. It was later on, when we became very isolated by having security and just working so much that we became very separate from the very things that inspired us, and then you end up writing songs about being on the road and that wasn’t fun. But at the beginning it was hilarious and really mad.

SDE: Do you think the fact that you were a little bit older than some of your contemporaries helped you deal with it a bit more maturely?

Alannah: In ‘84, I was 26. And Tom was 29, Joe was 31 or 32. But we’d had a lot of experience and we also came out of the squat scene. We did go off the rails, but that was later on.

Tom: I was probably a degree less stupid at 28 than I was at 18. Although sometimes stupidity amongst teenagers drives rock and roll forwards, because they don’t have the kind of control of their impulses with the old prefrontal cortex kicking in. Neurologists will tell us that that’s the reason. I don’t know. What the question really is, how do you handle the craziness, and is it easier to handle it if you’re a little bit older? And the answer is obviously yes, otherwise people don’t handle it and they crash land.

Stupidity amongst teenagers drives rock and roll forwards

Tom Bailey

SDE: Did you have a good relationship with Arista, your record company, in terms of their demands on you?

Tom: I think we did. There was a certain amount of advice to keep the American company at arm’s length because we were signed with the London-based branch of Arista, and we had a lot to do. I would go into the Arista office nearly every day to hang out, talk marketing ideas, artwork and so on, maybe pick up a few freebies. So it was a cool thing, whereas going into the office in New York was like, whoa, we have to play our cards right here. Otherwise we’ll end up having to do this, that or the other. And you know, to a certain extent that that turned out to be true. But we did have a good relationship with Arista, in London.

SDE: You’d already had a successful album with 1983’s Quick Step & Side Kick. Alex Sadkin had produced that album with you as well, of course. When you’d finished that record and you were starting to think about the next album, which would become Into The Gap, what was your game plan, what were your goals?

Tom: Interestingly, we were very goal and list oriented. We had band meetings discussing our manifesto, and how we’re going to achieve it; in order not to just drift aimlessly through the process. It’s very intense, so if you drift, you miss a lot of things. But right from the word go in the three-piece version of the Twins, we had a strict division of labour where we all got involved with writing, I did the music entirely. Alannah was writing lyrics. Joe was tossing ideas in. But fundamentally, the music was my side. Alannah was also working on the visual, the photography, the look, subsequently, the videos as well. Joe was thinking about designing the stage show, so we had three kind of separate areas, but when we actually went into recording Into The Gap, we thought let’s – more or less – follow the same plan to work with Alex: go to Compass Point first to cut the tracks and then bring it back to London to finish off in a mix. So that was the similarity. I think the difference was a couple of things. We weren’t quite so self-constraining with the instrumentation of Into The Gap. With Quick Step there was one guitar part on the whole album. We’d gone fully electronic. It was all synths and drum machines with a bit of percussion, maybe. However, suddenly on Into The Gap, guitars came back, pianos came back, so on and so forth – we broadened our instrumental palette. The other thing is, and this is more important, I think our songwriting had reached an emotional maturity where we were suddenly tackling bigger and deeper subjects. Quick Step is a great album, but it’s very heavy on the kind of quirky, eccentric side, rather than the heavier weight of emotions. There are no songs like ‘Hold Me Now’ or ‘Sister of Mercy’ on Quick Step.

We had band meetings discussing our manifesto, and how we’re going to achieve it

Tom Bailey

Alannah: With Quick Step & Side Kick we [originally] recorded the songs on a four-track in the front room. The first songs, they all came from storytelling between the three of us. I think the first thing we ever wrote was a track called ‘Kamikaze’ about how it must feel to be a suicide flyer. It was very beautiful and we were able to break it down. And it was fun. So we talked about that a lot, and then constructed it in the same way as we may have constructed a movie or a short film. I think a lot of Side Kick was like that. It wasn’t personal. None of that stuff was really personal. To us it was it was sharing and being excited by being in each other’s company and the threads of all the things we liked. Once we got to Into The Gap, and our second time working with Alex Sadkin – who was a brilliant producer, and who we loved working with – I think we relaxed a lot more. We had more confidence by then, and we were able to write a few personal songs. And weirdly, of course, the personal ones always become the huge hits, because that’s the unique thing that ties people together. It is love and death and glory.

SDE: Was it easy to get Alex Sadkin to work with you, on Quick Step & Side Kick?

Alannah: We were so naive. It was fantastic. I think we had four tracks on the demo tape for Side Kick. We sent off a tape, or the record company sent them to Alex in the Bahamas. At that point, I didn’t even know where the Bahamas was, I had been raised and brought up in New Zealand. I travelled a bit, but only directly to London where we were living in our squats. And suddenly we thought, oh, we really like this guy. We want to work with him. And then he said, come over in two weeks time and start recording. I remember walking off the plane in the Bahamas and we still had stinking leather jackets on. Of course, we’d chain smoked on the plane, probably the whole way there. We were just scruffy, smelly little brats, really. And there we were at Compass Point. It was amazing.

SDE: The key thing is you obviously had the confidence to go in and you weren’t overawed by the experience.

Alannah: If we were, we faked it. The whole thing about fame and that world is you have to have self-belief. As soon as your self-belief goes, you may as well just go. It’s like that with anything grand that you try in life. You have to have that self-belief and that confidence. We truly thought we were onto something; we thought we had written some great songs, and we had level of musicianship and a level of understanding of the world that we felt was good. Plus, we really liked each other, so the three of us together was really strong unit.

SDE: Was it all creatively driven? You weren’t thinking, “how are we going to have a bigger hit?“

Tom: I think we were, in the sense that we thought there’s no point in going into a studio until we know we’ve got at least four songs that do it for us, in the sense that we can imagine tapping our foot and singing along to it on a Saturday night. You can’t make the whole album like that otherwise it’s too constraining, so you just say what we need is four singles, they’re going to be hits, and then the rest of the album can be fun. We can explore all sorts of areas that we never expect to hear on Radio One or Top Of The Pops. We did do that, and once we realised that we had those four songs, which did indeed turn out to be the four singles, then we were happy to go in and start recording.

SDE: The songwriting credit on all the songs, it’s all three of you [Tom, Alannah and Joe Leeway]. Was that deliberate or is that just a fair reflection of how it was?

Tom: No, it doesn’t reflect the input in any way. But this is something that we’d established actually with the previous lineups of the Thompson Twins. Even in the seven piece, when we had a seven piece band, regardless of who wrote a song, I said we should divide this equally. There’s an advantage in that, which is that no one’s worried about getting paid and the subsequent effect of that is, if the writer takes all the publishing money, then other people are offering songs that maybe aren’t as good as the really good ones in order to get some money. It’s actually a quality control mechanism. Everyone’s going to get paid no matter what, let’s only have the best songs. Being paid equally means that we choose the best rather than, say, one of yours, one of hers, one of his…

SDE: Alannah, did you used to write lyrics on scraps of paper, or did you wait to hear some music and be inspired by it all?

Alannah: No, I always had notebooks. Funnily enough, I found something the other day, which was an old book where I’d been writing percussion parts. I didn’t know how to write music. I had my own sort of language for percussion parts, which was quite interesting. Like I said, often it just started with a story. We had a four-track, we had a small keyboard, and we had a little drum machine. This was right at the beginning and we’d just sort of record over and over and get tracks like that. Melodies would come in the early days from Tom, although they would be changed by Joe and sometimes changed by me. It was a real sort of three-way thing, but it always began with a sort of narrative, or Tom would have a melody that he wanted, that he thought was great with a beat, or Joe would come excited with something say, “My God, listen to this!” It was a real collaborative process. Tom, because his musicianship was much better, he was always given deference. But it was the same with me and all the visual stuff. People would input stuff, but it would be me that would make all the final decisions and work with whoever it was to make things happen

Alex Sadkin was up there with the with the greatest of the producers at the time

Tom Bailey

SDE: This is the second record you did with Alex Sadkin. Describe a little bit about what he was like as a producer and his impact on those two records that you made.

Tom: I’d say that Alex was up there with the with the greatest of the producers at the time. He really had a meticulous talent for getting projects through. Interestingly, he wasn’t really a musician. I think sometimes he would pick up a saxophone or something, and we would say “Put it down Alex, we’re not interested!”. He wasn’t really a musician, but what he was, was a sound engineer whose talents exceeded the job. And one of the reasons for that was he did an apprenticeship at Criteria Studios in Miami as a cutting engineer, because he came from Florida. Now, in those days, cutting engineers had to know how to get a record sounding good on vinyl. That was their job. If you made the snare too big, the cutting engineer would say “why don’t you make the snare a little smaller so you get more bass?” So that balance of sound was in his mind all the time. When we were making the record, he’s thinking, how is this going to sound on vinyl? How is the cutting engineer going to deal with these different frequencies and levels? He was very much designing the record in the back of his mind, as we were being the musicians playing the parts. And it just turned out that we had a certain natural agreement about that. I was throwing things at him that were unexpected, but it was always filtered through his sense of, that’s going to work or it’s not going to work on the record.

Alannah: Alex was so cool. He had been a marine biologist before he had become a record producer. He was a very clever, very laid-back guy. He just got where we were at, at that point. I was playing fire extinguishers, castanets and marimbas and weird instruments. You didn’t have to make an Alex record. You could make whatever you want. He made your record and that was something fantastic.

SDE: And would he have a team of people helping him in the studio?

Tom: It always took us three months to make an album in those days after the writing had been done. I introduced him to Phil Thornalley early on, who was our engineer. He’d worked on a previous album, Set, with Steve Lillywhite. And what happened was we ran out of time at Compass Point on Quick Step & Side Kick, so we said, let’s go back to London and finish it there. We did it at RAK, where Phil Thornalley was the house engineer there at the time, so that became the team.

SDE: Alannah, it was a very male dominated world back then, and I’m sure it probably still is, but what was it like for you, having to navigate that in the early ’80s?

Alannah: The first time I ever went on stage with the old band, which was a load of blokes, was in a pub in Richmond, and I spent ages rehearsing my part, where to come in, where to go out and as soon as I got on stage, these guys in the front just went, “Get your tits out!” And that was how it was. It was really confronting and really crappy. But on the other hand, I found ways around it. I invented hats, I invented a look that was very androgynous and refused to play that game at all. Never did tits and arse. We created cartoon characters. I think the boys did as well.

SDE: This album has really connected with people. Do you think it was what you were alluding to earlier, the emotions in some of the songs alongside the widening of the of the soundscapes?

Tom: That’s what I wanted to do after having experimented with a more purist synth sound. I guess I’ve got a soft spot for the for the wider palette, even the orchestral palette sometimes. But although I never really do that, it pushes in that direction. Just by chance, I happen to be a bit of a multi-instrumentalist, so I play the guitars and the keyboards. It means that I can get on with exploring those production ideas, those arrangement ideas, on my own, rather than having to call people in to do it for me.

SDE: Where did your musical talent come from, Tom?

Tom: I grew up in a family that respected music as a pursuit. My family were all medical and they didn’t like the idea of music as a career. They just thought it was something that a civilised person should do on the side. I think it was a massive disappointment for them, to take it too seriously.

SDE You took it too far!

Tom: Yes! Oddly enough, I was talking to my sister this week, who’s a doctor, but plays in a brass band, and she asked me to write something for her brass band. So we’ve come full circle there. But my father was a great amateur musician, an organist, pianist, and also an early Hi-Fi adopter. He built home Hi-Fi systems. That meant that even as a young child, I was listening to high quality reproductions of music around me. It’s something at the time you can never actually say, “oh, this is impressing me”. It was just part of my world. So it probably had a big effect. I was listening to full frequency, high quality sound, rather than the transistor radio that a lot of my contemporaries would’ve been listening to.

SDE: With your keyboard skills, you must have been delighted with the technological change in the early 80s?

Tom: Absolutely. I’d been fascinated by all that. Watching prog rock heroes that had big synthesizer setups. I couldn’t afford that. But in the early 80s, it became affordable, although even then, it was still the most expensive part of a group’s backline. You could get a guitar for £200 easily, or even less, whereas it was two to three thousand to get the keyboard. So you had to really want it and work for it. But of course, it opened the door to so much creativity. On the last album of the seven piece version of the band, we ran out of songs, and I had just got my hands on a synthesizer. I said I’ll just make a track. It turned out to be the hit of the album, because that night, I managed to pretty much finish ‘In The Name of Love’ at home, which was our first actual international hit. And so that was the writing on the wall for me creatively. I knew I had to pursue working with technology.

SDE: When you went on tour with this record recently as a solo artist, how easy was it to create the sound on stage?

Tom: Back then, it was a new era of using backing tracks alongside a live band, and how to synchronise those things, so it was a big experiment. We had a great live band. I think it was a seven-piece band we toured Into The Gap with. These days, we don’t use backing tapes, we use computers to synchronise all sorts of effects on stage. These things are a big part of the technological revolution. Sometimes it’s nice to get away from it, and in other projects sometimes I insist on no technological support. But everybody these days, and certainly in the pop world, is using technology as far as they can afford to, to make the whole thing brilliant.

SDE: Did you enjoy the touring in the 80s? Some bands love it in the studio – writing and recording the albums – but perhaps slogging around the world for nine months isn’t everyone’s idea of fun. How was it for you?

Alannah: For Into The Gap touring was brilliant. Well, actually, for those first two albums, it was really great. We had a brilliant band. I said I wasn’t going out unless we had women in the band. By then, I had some power to be able to go, “I ain’t going anywhere unless I got some more girls with me”. We got a fabulous keyboard player called Carrie [Booth], who became one of my best friends. And then my makeup artist, she also became one of my best friends and she came out and did wardrobe, because then we had more money to be able to do that then. You know, we had a few women riggers. We had women working in different roles. I purposely and consciously did that, and that worked great. At one point being on tour in America, the whole of the back room of the bus was just women and all the blokes had to be up the front. For me, that was triumph and revenge at the same time!

Tom: There’s the whole dynamic of leaving your family behind when you go on tour. The weird thing was Alannah and I were together in those days, so we weren’t suffering that dislocation. I actually enjoyed touring a lot, and I think Alannah and Joe did too. In the studio, they were kind of hanging around waiting for me to finish, whereas as soon as we got out in the world, they were engaging with people, and getting the adoration and feedback as well, which is part of the psychology of it. The big thing in those days was you lost money on tour in order to promote record sales and you’d make your fortune from records. And these days, it’s entirely the other way around.

SDE: ‘Hold Me Now’ became a hit while you were still recording the Into The Gap album, didn’t it?

Tom: Yes, I’m not quite sure how we came to that decision, but I think it’s because Christmas was coming, and we wanted ‘Hold Me Now’ to be out there. So we thought, if we go to the Bahamas and start recording, it might be three months before we even get anything back to put out. So let’s rush in. I went to RAK in London and recorded ‘Hold Me Now’, without Alex. He turned up at the very end and got me to re-record some of the vocal lines but all the music was done before he arrived, and it just sounded fantastic. So we said, okay, let’s mix that, leave it with the record company and go off and make the rest of the album in the Bahamas.

‘Hold Me Now’ was fanastic. It was a magic moment. Everything just gelled.

Alannah Currie

Alannah: We knew we were onto something with ‘Hold Me Now’. It just worked. It was a magic moment. It was fantastic. Everything just gelled. It just came together. There is very much a thing in songwriting – and the same actually in art making, because I’ve done that for the last 20 years – where there’s a moment where you just know things work. And in a way, you don’t write the song, the song writes you. It was like being in a very dark room, and suddenly you put your fingers through holes in the sky and connect with something that’s so universal. And I do believe it’s magic, and we can all, as artists, make up theories about it, but it’s something really quite wonderful when that happens. And ‘Hold Me Now’ was one of those moments.

Tom: ‘Hold Me Now’ was put out in the UK and internationally, and particularly in America, we started getting these phone calls saying, “it’s going up the chart, it’s really exciting, it’s going to be massive”. I remember these phone calls, because in the Bahamas, you actually had to book time to get a phone call in. We’d all be sitting around the speaker listening to the phone call, and it’d be someone saying, “it’s gone crazy in America”. So that had an interesting effect on us, which was it really excited us to realise that we had to make the album as brilliant as possible. We had a flagship out there doing business for us, to ignore that would have been crazy.

SDE: Did the record company ask to hear demos before you went out to Compass Point to record the album, or did they leave you to it?

Tom: No, I think they only did that on Quick Step and Side Kick, because that was like a new project. By the time we got to Into The Gap, it was our habit to leave London and go on a kind of writing residency. We’d rent a kind of lonely farmhouse, somewhere where it was difficult to go to parties and clubs, so that we would actually just work. And we did that somewhere down in the Romney Marshes [in southeast England]. We had a house, and I remember Alex coming along and listening and he was happy and we were happy.

SDE: So you weren’t coming up with new songs in the studio when you were recording the album?

Tom: Well, I think that some of them were more complete than others. So some of them were bare bones of ideas that we had to flesh out in the studio. I was also getting into the beginnings of programming, which was completely unreliable. I remember going to Compass Point with more or less the whole rhythm section of the album programmed on an Oberheim machine [OB-Xa], on Quick Step this was, and we were hit by a big thunderstorm that night. The studio got struck by lightning and it wiped the memory of everything I’d been working on for weeks, if not months. I had no backup, but in those days I could just remember all the parts anyway, so I did it by hand. So things that had been really kind of rigidly played by a machine I ended up doing by hand. Maybe in a funny kind of way that gave it a kind of human feel. I don’t know. They’re kind of subconscious things you can’t really evaluate. But I often wonder if that was the case.

SDE: We should talk about the Dolby Atmos mix, because David Kosten [who created the mix] told me you went round to his studio and listened to it in all its glory with the multi-speaker up. What did you think of it? And what do you think of immersive audio in general?

Tom: I remember Alannah was kind of suspicious and I was relatively ignorant of the whole format, so I was kind of interested. And it’s a shame to have to say this, but my hearing isn’t what it was. I’m coming up to 71 and I’ve lost a bit of high frequency through age and abuse. So I don’t trust that I could hear all the detail that was being presented by the Dolby Atmos experience. It sounded great to me, but I said I can’t be the one to make the final call on this. You have to be sure that you’re doing the right thing. However, I did notice a couple of things that I thought weren’t right and asked them to be fixed. And so I was really glad to hear it that way.

Alannah: I just got the air pods yesterday and listened to the first part of ‘Hold Me Now’. And that was really lovely. I’m not an audiophile, particularly, but it was amazing.

Tom: To your question about what I think about the format in general. I mean, I’m aware that there aren’t that many people in the world who can actually listen to Dolby Atmos…

SDE: Well, this is the thing. There’s different levels now, in terms of listening to it. Headphones via streaming, full amplifier/speaker set-up with blu-ray audio…

Tom: I’m quite happy for there to be so many different ways of listening to the same piece of music. In fact, part of the Thompson’s legacy, is we made different versions of everything, dub mixes and extended instrumentals. It was part of the mindset that there is no singular way of listening to something. We didn’t even have the phrase post-modern in those days, but it was part of the revolution of deconstructing the singular authorship of anything, and I think that in that sense, it falls directly in that tradition. It’s just a new way of listening to something which is hopefully exciting and entertaining and interesting, and reveals something in the experience that wasn’t available before. So that’s how I see it.

SDE: What your abiding memories when you when you hear the album today. What does it mean to you?

Tom: Listening to anything that I’ve done in the past, for me, is like reading an old diary. It connects you with the past. You remember the people you were hanging out with, the ideas you had, the excitement of it, the stress of it, because it was really, really hard work, and we gave ourselves incredibly difficult goals to achieve. We didn’t fool around too much. We worked really hard. So those are the memories I have. I think there are a couple of albums in my career where everything seemed to just fall into place in that magical way. And Into The Gap was one of them. The other one, oddly enough, was the first Babble album [1994’s The Stone], which is what the Thompson Twins became when when we imploded into an underground band again. I really like the first Babble album, but from the more well-known era, definitely Into The Gap. I can’t see anything wrong with it.

Alannah: It was just extreme madness and a lot of fun! It was so high pressured, but we also had loads of resources available to do whatever we liked and go wherever we wanted. It was also very out of control, the whole thing. You just got on this high-speed train that somehow let you in, and you were on it, and there was no getting off it. You just couldn’t get off it. You just had to ride it and see where it ended. That was it. It was mad. It was totally mental.

SDE: That’s a good analogy. You couldn’t get off the train, just waiting for it to derail at some point?

Alannah: Absolutely, you were praying for a crash. And I think probably that’s what lots of people do in the end. Because we’ve often joked, Tom and I, that it was easier to get a divorce than it was to get out of a band!

SDE: You’ve got all these external pressures, haven’t you?

Alannah: Everybody’s so invested in you being in the band. Everyone, from your sisters and your mothers, because everybody gets prestige out of knowing somebody in a band, to all the people who are on the road with you who have got jobs, to people paying off their mortgages because they’re in your office and they mistakenly think they’ve got a job for life. It’s really hard to get out of, so the pressure is absolutely enormous. And to have to say to all those people “Bye, we’re leaving”, it’s just terrible. You make everybody redundant in every way. We’ve still got sisters and aunts and uncles and people going, “When are you going to reform? When are you going to be on Top of the Pops again?” And you go, oh for god’s sake, give it up! I’ve done it for 30 years. They’re desperate for that stuff, and I get it, but don’t want it.

SDE: So presumably, there’s no chance of the three of you ever getting back together and getting up on stage again?

Alannah: I can’t think of anything worse, to be honest. It was of its time. It was brilliant. But I don’t reflect much, I don’t go back. I still feel like I’m going forward with ideas. And you know, touring was fun for a while, but by end of it, just no, no, no. And Tom and I were married, we were together for 23 years. We have two children now, and grandchildren together. So we’re sort of family, but there were reasons why we divorced. It’d be very hard for us to be in the same room for longer. We have meetings, but we don’t really want to hang around with each other too long.

That was another aspect to our whole band thing: we never had a ‘wife’. If you look at all those pop stars, they all have wives to look after their lives, to look after their children. Tom and I were doing the same thing. We were involved in the same work at the same level and it was very hard to have any sort of cared for life. We were very isolated and on our own. And then once we had children, there was nobody to look after the house and the children, like those other pop stars, it was just us. I don’t think children and being in the music business go together at all. I didn’t want my kids raised in the music business. So for me, it became a choice at the end – quite a determined, clear thing that I wanted to have a family. I prefer that over music.

SDE: Into The Gap was the most commercially successful of your records. But does that mean it’s your favourite?

Tom: I don’t know about favourite, but the arc of our celebrity coincided with our one of our best pieces of work. So in that sense we were lucky. By comparison with the first Babble album, everyone had lost interest in the Thompson Twins, and we were doing great work, but no one was listening to it. Similarly, there were other Thompson Twins albums during our period of celebrity, which weren’t 100 percent brilliant. People were listening to them, but there were some kind of bad patches on there. It doesn’t happen with every album, but with Into The Gap, it happened.

SDE: Is this reissue something of a new start? Now you seem to have a positive relationship with BMG, is there a road map for what’s going to come in the next few years?

Tom: I don’t know. Everyone on their side is doing a good job, and there’s talk of greatest hits sets, there’s talk of a live album that they’ve discovered. There’s talk, inevitably, of Quick Step and Side Kick getting the same treatment. I’m not sure how keen the other two are about it because from their point of view, this is just kind of remonetizing their past and there’s no real creative input for them, whereas for me, it makes total sense, because I’m back in the live business. So, to have albums out that have been promoted by a record company is a massive plus for me and really exciting.

Alannah: We had a really bad record deal previous to signing with BMG, we only signed with BMG a year ago, or not even that, six months ago… eight months ago. I think it took three years to renegotiate a deal with BMG. It was suddenly like they were human beings, cool people again and they suggested putting Into The Gap out. They want to do a live album because they’ve found all these tapes. They hadn’t listened to any of this stuff. Nobody had listened. It has effectively been in the tombs gathering dust, in the basement of whoever’s archives.

Thanks to Tom Bailey and Alannah Currie both of whom spoke to Paul Sinclair for SDE. The Into The Gap 40th anniversary reissue is out now, although sadly the SDE blu-ray audio has sold out.

Compare prices and pre-order

Thompson Twins

Into The Gap - 3CD deluxe

Compare prices and pre-order

Thompson Twins

Into The Gap red vinyl LP

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Interview

Interview

SDEtv

SDEtv

By Paul Sinclair

37