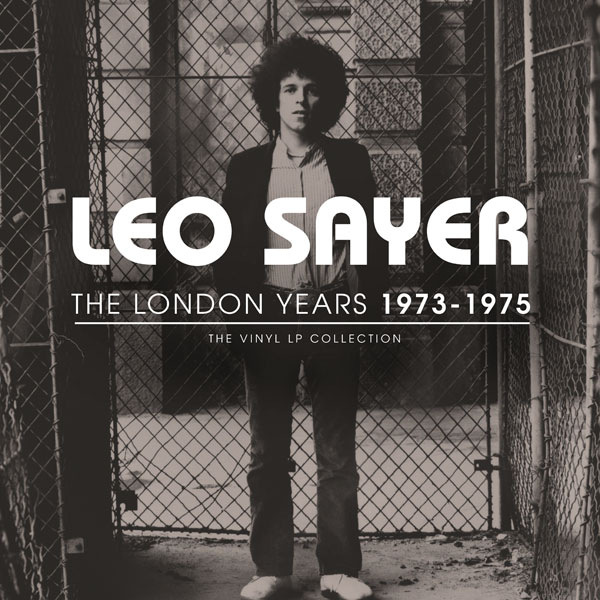

Leo Sayer: 40 Years in Music part 2

Late last year we spoke to Leo Sayer about his 40 years in the music business. We chatted for so long that the interview was split into two parts. If you haven’t read part one then you should click here first, but FINALLY (!) we bring you part two of the story of Sayer’s career. He had just arrived in America in the mid 1970s and manager Adam Faith was determined to make a success of Leo in the United States…

Leo Sayer: When Adam [Faith, Leo’s manager] said I was going to work with [hot shot producer] Richard Perry, I said “What? – he’s boring!” I didn’t want to do that, I wanted to work with someone groovy and funky! I was finding my soul. But anyway, we had a meeting with Richard Perry and he was very dynamic, it must be said, but he said “I don’t see you as a songwriter”, and I went “What?!” – because that’s what I did, I was a songwriter – but he said “No, no it’s the voice I’m fascinated with”. So there was a lot of arguments. One time I was going [to go] back on the plane and Richard called me and said “turn the car around and come back to the studio”. So I went back and there was this amazing array of musicians there. So I thought, I better do this… I gave in on a lot of my ethics with “Endless Flight” but it turned out that it was an album where the first hit on it was a Leo Sayer song [“You Make Me Feel Like Dancing”], so out of all of that Richard Perry posturing, saying “you’re not going to write any songs” in the end he turned around and said the first single is going to be that song you wrote [laughs].

It all happened in the studio. The scenario every day was we’re gonna do this song, or that song and me and the musicians would jam. Mostly, me and Jeff Porcaro would instigate it, along with Ray Parker Jnr – we all loved to play together. They loved my voice and I loved their playing. So Richard used to record the jams inbetween and one of the jams was “You Make Me Feel Like Dancing” and the jam became a song.

SuperDeluxeEdition: Not many British artists have had consecutive US number one records [“You Make Me Feel Like Dancing” and “When I Need You”]. You must have felt indestructible?

LS: Yes, my sparring partner was Rod Stewart. We used to talk about that all the time. You know, “you wait to you hear my new one..”, “Fuck off!” [laughs]. It was really funny. But I was motivated by being in America and playing with these musicians and it felt like I must not waste a second. The brilliant thing about Richard is that he knew all the muscians and he could get them to play. He booked very intelligently. On the “Leo Sayer” album, the third album [in the US] my guitarists were Waddy Wachtel and Lindsey Buckingham.

So we went in and used the band, and it was the first time Richard had worked with Steve Gadd, and he said, “this guy… we have to keep this!”. Steve had such a feel on “You Make Me Feel Like Dancing” – we’d tried it before, but we hadn’t quite got it, and Steve just had this lovely back-beat kind of thing, like he does on 50 Ways To Leave Your Lover, and he did it in “You Make Me Feel Like Dancing”, and it was just amazing.

SDE: During that Seventies era, there seemed to be an amazing array of talent, in terms of session musicians.

LS: Yeah, ‘The A-Team’, they called them …they were great. You had to be careful as well, because it could cost a lot of money to make records. Some of them were so famous they charged ‘triple A’ scale, which meant three times a two-hour session fee.

SDE: It’s amazing that Lindsey Buckingham played, because you wouldn’t have thought of him as someone that would do session work for other people.

LS: Yeah, and the lovely thing was, Waddy [Wachtel] – who to this day remains such a great buddy – Waddy was a bit wasted at the time, so Lindsey used to leave his house and then come and pick up Waddy, and drive him to the studio, and I always thought that was really beautiful.

SDE: Is that him playing acoustic guitar on “Something Fine”?

LS: Yeah, “Something Fine” is just me and him. A Jackson Brown number. And we both love that song. I mean, Richard chose it, and he said, you know, you should try this, because the album was going in a much more folky direction. He played me some Jackson Browne stuff, and I loved it. The only problem was that a lot of Jackson’s songs are – in a way – very long-winded, so this was one that we thought if we did it really simply, it would work, but if we’d done it with the band, it might have felt a bit turgid, to be brutal. And Jackson was a friend as well – he bought my bus off me! I had a tour-bus at the time, and he took that bus and turned it into a recording studio, it was lovely, the MCI, and did his live album on it. He’s a beautiful man.

SDE: Can we talk about “Thunder in my Heart”? Originally released in 1977, it became another big hit for you again, famously in 2006. Now what I want to know – and be honest here – I mean, Meck “featuring Leo Sayer” – you must have thought, well, hang on, it’s my bloody song….

LS: No, the real story behind that is very different, I own the song, and it’s mine – I went through years of management shit, and various lawyers, and everything… so basically, the ownership of all the tracks came back to me. Richard Perry would still try and claim some extra producer’s money, but we weren’t having that, so we managed to block him. You got paid very well, my boy! [laughs].

Without dishing the dirt on the story, there was all the masterminding of a chap called Clive Black, and I’m sure you know Clive Black – [lyricist] Don Black’s son. Anyway Clive was moving into the DJ kind of area, after leaving EMI, and really into new music from clubs, and everything and he had this guy called Craig Dimech. Craig ran a dance label for him. So basically, they got hold of a team called Bimbo Jones, which was Lee Dagger and a guy called Marc JB (they were partners), they made the record. They tried to do something with it but the problem was that Richard Perry had held onto all his masters – multi-tracks – because I think he, you know, he wanted paying more money before he delivered them over … and the only [other] multi-tracks that we had, well, Adam [Faith] put them on a funeral pyre, so that I couldn’t make any more money, because we were in dispute against each other.

SDE: Lovely… [laughs].

LS: So all I had was a stereo track, you know? That’s all they could find, so they took the original record, and [were] filtering. The boys – Lee and Marc – did an absolutely amazing job with it, it must be said. So look, I knew all about it, cos they had to ask my permission. But here’s the rub – Clive Black had gone to my record company at the time, and also gone to the publishers, and said, I just want to use 30 seconds – no, actually 20 seconds – of Leo Sayer for a track that I’m doing with a DJ. So, that’s all they paid … that’s all he had to pay for.

SDE: What, even though they didn’t do that?

LS: No. Absolutely. Completely lying through his teeth, but that’s the kind of games that used to on, you know? So anyway, it was all given away. When I enquired, I said, this is fantastic, we’re going to make loads of publishing money out of this, but they said, well, actually Leo – you’re not. Because …

SDE: That’s ridiculous. It is basically the whole song

LS: Just [shows] the music business for you, doesn’t it? It’s my vocal, from 1977. Gene Page’s strings. Everything’s there … They managed to just erase the drums and put some beats in … and did a bloody good job.

Look, the scenario was not nice. And I was really fucking pissed off. You know, can you imagine, and Donatella managing me – Donatella Piccinetti – she just wanted to block it. But we were packing for Australia at the time, and getting everything together, and I was [in a tiny little] studio trying to make some music, and I hadn’t packed up my speakers and my desk quite yet, to go to the container for Australia, when what they’d done, and what [Meck] claimed he’d done, but actually it’s what Bimbo Jones had done … came through the door. Clive Black knew he couldn’t speak to us, so he sort of said, maybe you’ll change your mind about this when you hear this. And fuck me, I did. It sounded amazing – it wasn’t quite finished, but Jesus Christ, it worked. They’d speeded it up – but somehow managed to keep the vocal pitch; they’d put new drums and new bass on; they’d cut up the song and they’d taken that part ‘take me baby, I’m all yours’, and just repeated that, repeated that – and it was so fucking brilliant. I mean, I was bouncing off the walls. I just turned around to Donna and just said, smash, absolute smash – my God!

So then under my instruction it, with all the people around me, my lawyer and everybody, and the publishers – [I said] look, just forget the bullshit – we’re not going to win with these people … we’ve given it away … but let’s just make it happen. Let’s do anything we can do to facilitate it. And they agreed, you know, my publishers, when they heard it they went, “oh yes”. I’d had a crappy year in England. Basically, I was off to Australia, where there were loads of offers for work and everything, and a good band I was putting together out there, and everything …

SDE: So you were basically emigrating, weren’t you, at this point?

LS: I was emigrating. I had four gigs offered to me in England – I couldn’t afford to keep my band going. They were all sitting around waiting for work, and there wasn’t any – and BBC and ITV were having me do crap ‘this was the ‘70s’ programmes, and hosting that, and all I could get was “Vic and Bob” shows. I had to do stupid fucking stuff, or … would you believe Jimmy Saville, doing “Jim’ll Fix It” – you know, I had to kind of do shit like that – it was just awful. So I was over England anyway, and ready to move. I was thinking, blue skies and lots of work, and a new manager. So when I heard this, it was just like, oh, my God, this could be it – this is icing on the cake.

So by this time I’d worked out also that Clive Black was a shifty bugger to work with and it was all very much in their hands. They started to say, well, if we’re going to put this out, we’ve got to be your managers, so we had to kind of do a deal with them to do that in England, and they were a bit useless, it must be said, got me into “Big Brother” as the big scenario – that was all the TV they fixed, and it was bloody awful … but look, the record did fly …

SDE: Yes, number one – you can’t get much better than that. Anyway, let’s zoom back to the late ‘70s. You got back together a little bit, semi-reunited with David Courtney for the “Here” album.

LS: A couple of times we got reunited, cos he did some of the songs for “World Radio” – in fact the title song was me and him.

SDE: So you basically patched it up?

LS: Yeah, well, Dave was in LA., and… we did three albums with Richard [Perry], and quite frankly I don’t think according to Adam, we could actually afford to do any more with him, because every time his producer’s cut, or price, would go up, you know?

That’s America for you. And meanwhile, [at] about the end of this time, Dave had been contacting me, because he was now a fully-fledged producer, and in America. He was saying, oh look, I’m working with Steve Cropper, and Duck Dunn, and all these great musicians – why don’t we get together and try and write something. I said “fuck, yeah”. So he was staying just up the road from me, and so it was a natural progression. He had a great keyboard player as well, with him – Billy Livsey, an American who was working in England, who came over to do work with him – and the three of us just sat down and said, I think we have the bones of an album here.

He had a really good deal, as well, with Sunset Sound Studios, which I loved, and where Jackson [Brown] used to record. So it was kind of easy, it was a logistic easy, and Adam thought it was great, as well, so we just piled in, and we made “Here”. It was fantastic – suddenly an album that cost nothing to make compared with all the expensive Richard Perry albums. It was a joy.

SDE: And that would be your last album of the 1970s, before you moved back to England at the beginning of the ‘80s?

LS: Yeah… Chris Wright, at Chrysalis said, “look, I’ve found this really interesting guy who’s worked with Cliff Richard” [Alan Tarney], and I went, “Oh dear” – and then he played me “We Don’t Talk Anymore”, which was just about to be released, and I think everybody in the industry thought this was an amazing-sounding record – you mean one guy did all of that?! It was a new kind of concept, so, shit, yeah, I go “I’ll meet this guy”, and they played me a couple of tracks that he’d done, and I thought it was a really new and interesting sound – a whole different approach. I was spending a lot of time back in England, and I was ready to move out of the States – hadn’t quite moved out of the States, but … everything seemed to be at that time getting expensive and a bit silly, and there was too many drugs around, anyway. So I walked into Alan Tarney’s little studio in Acton – were supposed to [just] be having a meeting – and we wrote four songs that day. So, bang, we were going. It was terrific.

SDE: So it’s kind of like the opposite scenario wasn’t it? You went from collaborating with a massive range of musicians to working with one person!

LS: Suddenly we’re working in this little studio in Fletcher Road in Acton, and the only famous person within 20 miles is Nick Lowe, who’s got a studio up there as well… and it was all really funky, you know, carry your own gear in, and Alan and I just working together with with an engineer. Sometimes no engineer, and all done for peanuts [in terms of budget].

But it was so much fun. And Cliff would pop in, because he was very friendly with the whole setup, that’s where he’d made his record. We were so prolific. We had a creative format. Alan would push through the basic song and the basic music, and then I would influence it in various ways, as he’s doing it – just an acoustic guitar, and putting down the rough track, and then immediately, we’d make a cassette I’d jump into my car and I’d drive around with a microphone in the car, and make up words. And we wrote nearly all the songs like that. And I’d sort of come back an hour later, got it! It was wonderful, it was back to a cottage industry that I’d experienced with Dave [Courtney].

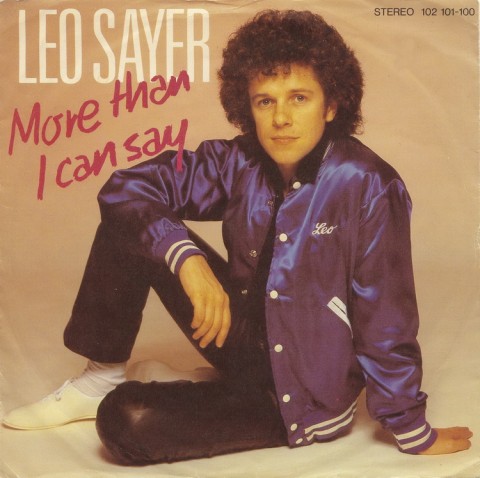

SDE: The irony is, you had a really big hit in the US with “More Than I Can Say”.

LS: The whole studio plan was great with Alan, we were so prolific, and we were so fast, that we ended up with a day free. On the budget we had, a day in the studio was sort of like a beautiful bonus. So we thought, what the fuck are we going to do with it? We ended up looking at the TV, you know, bereft of ideas. We thought we’d do a cover, which would be fun, and add that onto the album. Maybe it would be a B-side – that’s all we thought. Because we already had the record made, but Ruth who ran the studio, said, well, you’ve still got an extra day, guys, you might as well use it.

So there we were, we weren’t going to waste it, and the [ad for the] Greatest Hits of Bobby Vee comes on the TV, and there’s this song “More Than I Can Say”. We both looked at each other, and I said, “Shit, I loved that song, that was one of my faves”, and Alan said, “Me too – well, let’s do it”. So the only problem is, with an ad on the TV you don’t even know if the record’s out, so we went to about three record stores before they found one that was still in the box, and the shrink-wrap, you know? We managed to get them to open it and give it to us. [They said] “This isn’t officially on sale, yet. But since you’re Leo Sayer, you can have it”. [laughs]

So, you know, we take it back to the studio, have a listen and work out the chords, and by one o’clock we had it mixed and done. And then we added it as a bonus. When we played it to everybody, we said, “Oh, and we’ve got this, as well”. And they all said, “fuck me, that’s your hit, you know?” [laughs] Adam, as well, and everybody just said, that’s it. So what was just a complete accident of a booking mistake became the big hit, and it brought me back to America, yeah, and it went to Number One in the country charts, and it really re-opened everything, it was fantastic.

SDE: And of course some pop fans will know Alan Tarney, because he had a big success with A-ha in the mid-‘80s, didn’t he?

LS: Yeah, that was afterwards. But they would know him, yes, from that, of course, and also from all the Cliff tracks.

Also [The Dream Academy’s] “Life in a Northern Town”… that was him as well, so he was a very clever man, and still is, still making great records. Of course, we came back in the studio, had a brief session which led to Orchard Road. We had another single with our version of “Unchained Melody” which was [recorded] one night when we were drunk. I think the demo is actually better than the record, though. Thank God, the demo is actually on “Just A Box”.

SDE: Did you start to get a bit disillusioned in the ‘80s, with the industry?

LS: Oh shit, yeah. I mean punk had already kind of like moved people like me into the scenario of joke artists, so it was very, very difficult. And then that sort of Pete Waterman kind of period was very destructive, as well – I think even more destructive than punk. Because the idea that they could take a boy from the post-room and just turn him into a hit artist, and take an Australian actress who – in my mind – could barely sing and turn her into a megastar… it all became that kind of scenario. So it really wasn’t based on sheer talent, as much as sheer Svengali management. It suddenly turned into a machine in the ‘80s. So, yes, it was very hard to fight that. I would go to people like Muff Winwood [A&R man] at CBS and he’d say, “Look, I love the songs you’re doing but it’s just not commercial, I’m afraid”. I’d have had to really prostitute myself to … in fact, Stock, Aitken and Waterman… I did actually go and do a track with them.

SDE: Oh, really?

LS: And it was so fucking awful that I just didn’t want to do it. I never sang it, the final vocal – I just said, no, sorry, I don’t want to do this. But you know, people like Lulu, and Cliff, and everything, were doing stuff with them, and… it sounded awful.

Maybe should have gone with it, but I’ve never ever wanted to do anything other than the music I’ve wanted to do, I always wanted to stick to my credo and be really happy with everything you’ve done. But there are a few crimes in there… I started a great album with Chris Neil, and it was just basically us having fun and doing some covers, and it ended up being “Have You Ever Been in Love?” Because the marketing dogs had kind of come into the industry at that time. When Chrysalis heard what we were doing, they just said, “Yeah, but we have to put some hits on it”. So already the ‘Greatest Hits’ scenario was starting, so that album, for me, it’s cursed by having songs that have already been released on other records – hits – joined onto it. I suppose it was nice at the time that “Orchard Road” made it onto an album, but I didn’t really see the point, I was getting very disillusioned with England at that time. As I think a lot of people were.

But then, suddenly, Arif Mardin wants to work with me, and so off I go to America [laughs], in 1982, and I thought we made a very good record. Dave Courtney was also kind of involved in that, and … that was just a really interesting record. We had “Have You Ever Been in Love”, which was going to be a big hit, but the original version got released, and I think there were some dirty tricks in trying to plug that into the charts and maybe not plug my version. The industry was very much controlled by the pluggers.

SDE: You ended up taking an extended period out of the industry, not really releasing anything…

LS: Well in 1990 I went back with Alan [Tarney] and did “Cool Touch” but the only problem was we really got scuppered politically there. I thought it was a bloody good record, but we probably couldn’t afford enough for the marketing team and [the] promotion team – that’s where you need to spend the money these days, and that’s why records aren’t as good, I reckon, because people spend less money on producing, and more money on pushing. I’ve managed to get it back, reinstated onto “Just a Box” which is nice, so the album “Cool Touch” can be seen now, and heard.

SDE: So what did you do between that album, and the ‘90s and the early noughties?

LS: I was still trying to deliver stuff, but nobody wanted to know. You kind of fall out of fashion. But meanwhile, I’m still going down to Australia, South Africa, America, and the Far East…

SDE: So you’re were doing a lot of live work, basically?

LS: Yeah, and the records were having a new life, because people were buying them and … so it’s all good. I mean, apart from a bit of pirating every now and then, but at least you’ll know that you will get some legit sales [laughs] in the middle of all that. Australia was very much keeping me going, because everybody over there was saying, “God, you’re so current, Leo – rather than, in England, like when I go to see Muff Winwood, he said, “Well, Leo, you had your success in the ‘70s, why don’t you just lie down and take a powder?”.

SDE: England has always been a bit fickle in terms of image and everything, hasn’t it?

LS: Well, it’s all about young, young, young, young, young … it’s just the music industry stitching somebody up afresh, you know? You look at the contracts of the people on “The Voice” or in “X-Factor”, and you … I mean, nobody in their sane mind would sign that, would they? You know, I give you 80% of my career, and I’ll have the other 10% to work on, and please God, I get a deal with Nike, to wear their shoes [laughs]. It’s like, it’s not really a model for a career, is it? So it all becomes like, “let’s make lots of money” like the Pet Shop Boys say… while we can. It’s short-lived, isn’t it?

SDE: So when you look back on your 40-year career, what do you pinpoint as some of the highlights?

LS: I think overall, I’m very happy that I stuck to my guns a lot of the time. And I’m really happy that – although it wasn’t planned – the records all sound different. So it kind of leads to lots of varying highlights. So I could say, right at the start, listening to Roger Daltrey’s first single, “Giving It All Away” with David Courtney. We had to listen to it on the radio in the car, so that was a great. When it actually finally came on, I can’t tell you… the goosebumps, the adrenaline, it was just, yeah! So I’ll never forget that moment, even though it was Roger, not me, singing – it didn’t really matter, it was like, we were away, you know?

And then, when “You Make Me Feel Like Dancing” went to Number One [in the US], I came into New York and we were playing a gig, I think we were playing Radio City, or something like that. I knew it was going up the charts, but I was always too scared to look, because things either happen very fast or very slow in America. The pluggers have a strange way of not wanting to let you in on the whole scenario, in case they fuck up as well. [laughs]. So they would never really tell you exactly. So I’m in Bergdorf Goodman, a store, with my ex-wife Janice, and we’re just looking at leather jackets that we can’t afford, and suddenly somebody shouted out, ‘There he is, he’s Number One!’ And I was kind of marched out the store, and put on people’s shoulders, and taken down the road on Fifth Avenue, to the Plaza where I was staying, and cars tooting, everybody stopping, police kind of like [putting] a cordon, and there was about 100 people marching up the road, [I was a] new-found hero. What a beautiful moment, you know?

And then there’s the Grammy, which I missed.

SDE: why weren’t you there, then?

LS: Yeah, because the British Airways screwed up, and I couldn’t get over there in time, so I arrived late, half-way through the ceremony. I sit down and Count Basie – who’s sitting next to me– turns round to me, and says, “Son, you just won a Grammy”.

SDE: Well, you still got a Grammy, I mean, that’s pretty cool.

LS: Yeah, no, it’s good. That was a little Grammy [it won Best Rhythm and Blues song] – but it really was up for Song of the Year – and we missed by a whisker, apparently not many votes difference, they told me in the end.

SDE: Tell us a little about what’s happening now, cos you’ve got this tour coming up. What can people expect, is it really going to be just a good old greatest hits?

LS: No, it’s two hours a night, and I’m piling everything in, and we’ve managed to include a couple of new things as well, one song I found from 1975. It’s an interesting show, and there’s a few rarities in there, there’s songs like “Train”, from “Just A Boy” and “Tomorrow”, from “Silver Bird”, in there but the hits all stay there, they’re all there.

I think probably the only one we don’t do is “Dancing the Night Away” – which doesn’t really work out very well onstage, because you need a fiddle-player, but “Have You Ever Been in Love” is there, and “The Show Must Go On”, and “Long Tall Glasses”, “How Much Love” – and we even do my Christmas single of 1975, “Let It Be”.

SDE: you did a few Beatles songs didn’t you?

LS: Well, yeah, that was one of the bugbears of doing this project, because we [ended up with] two bonus albums, and it was going to be 166 tracks, but there was some stuff that – because of all the mess-up with EMI’s catalogue being going over to Universal – they still haven’t cleared a lot of the stuff. So my lawyer said it was too risky to put it on there. I have a great version of “The Long And Winding Road” that I did with the London Symphony Orchestra, with Lou Reizner and it was Wil Malone’s first-ever string chart – Wil Malone who did Bittersweet Symphony, of course… an amazing arrangement. It was the first time he’d ever worked, and he put together this amazing thing for “The Long And Winding Road”, that I wish it was on the album [box set], but we didn’t quite clear it in time. And then there’s something I did with the Alan Parsons Project, as well, an album called “Freudiana” – but Eric Woolfson died not that long ago, and nobody can work out who owns the estate.

There’s “Tears of a Clown” [on the bonus discs] which during that time I was arguing with Richard Perry, was the only common ground we could find before we started out on “Endless Flight”. “Tears of a Clown” is great, because that’s Willie Weeks on there playing bass, an outrageous band. Those guys – Ed Green on the drums – we wanted all those guys on the session, but by the time we’d started they were all unavailable [laughs]. There’s some interesting rarities on there … “Living in America”, of course …

SDE: You’ve got the original disco version of “Thunder In My Heart”, which is probably quite rare, I don’t think that’s ever been on CD.

LS: Yeah, Mike Neidus from Demon, found that, because he’s a big disco fan. So we said, “shit, let’s put that on there, that’s great”.

SDE: Now what about your new record though? Is that finished, are you in the middle of working on it, what’s the situation?

LS: Yeah, still working it up. What I tend to do these days, the way I write is, I write everything in my head and then put it down later on. But it’s an interesting record.

SDE: So when do you expect that album to be released?

LS: Oh, I think it’ll be out for next summer. As you know by now, I’m not a rusher of things. [laughs] But, yeah, all the songs are done, all the songs are written, I’ve just got to finish it off now, so I’m going to use this lovely hot time in England – thank God I’ve got an air-conditioner in my studio – to finish it all off [laughs] when I go back, so hopefully by mid-January, that will all be mixed and ready to go. I’ll probably have to release it on my own label – I don’t know.

The music business is weird, but the main thing is to get it out there and put some videos together for it on YouTube… and that’s what you do these days, you don’t expect to make money on it – you kind of hopefully sell a few when you go on tour. But it’s a labour of love, that’s what we do. You know, the Spotify guy has made how many billion, and none of us are getting paid. [laughs]

SDE: It’s all changed, hasn’t it, the music industry?

LS: It’s fucking changed, but I mean, I just still love making records. And I’m just so proud of “Just a Box”, because everything’s on there. Mind you, we’ve got some work to do now, because I’ve got to persuade Australia to release it, and the first thing they all turn round and say, it’s too expensive to produce. That’s why I did all the artwork, I didn’t want to have to pay money to do it to get anyone else to do it, you know?

SDE: But of course, that all makes sense now that we know that you were a graphic designer in the early days.. [see part 1 of the interview!]

LS: Yeah, I’ve had a great artist help me finish it off, as well. He did all the final bits on it, he made it all [make] sense, you know, did the final lettering, and little bits like that, so we went between each other. But basically, yeah, the main part of it, all the collages in the book, and the colour-coding, and all that sort of stuff – that came from me. And the liner notes – so I spent two months putting this together and I’m very proud of it.

Our thanks go to Leo Sayer, who was talking to Paul Sinclair for SuperDeluxeEdition.

Just A Box is out now – full track listing can be viewed here.

Interview

Interview

By Paul Sinclair

15