Pete Waterman on PWL, Kylie and Judas Priest

“It’s like the we were the Antichrist”

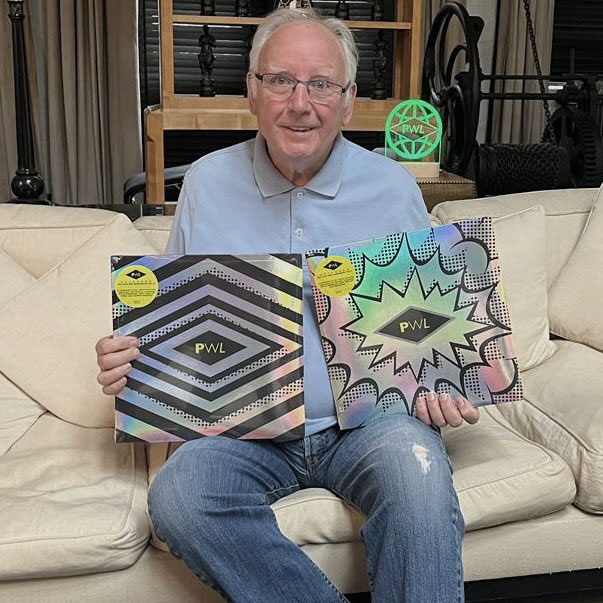

With PWL Extended: Big Hits and Surprises just released, SDE caught up with hitmaker and music entrepreneur Pete Waterman to discuss his time writing and recording singles and albums for numerous acts and running a small business that grew exponentially towards the end of the 1980s. “I regret not selling Kylie to EMI” he tells Paul Sinclair in this revealing interview…

SDE: Did you have any involvement with selecting the tracks on PWL Extended: Big Hits and Surprises or are you just helping out with the promotion?

Pete Waterman: I left this to BMG. I think sometimes I’m too close to this stuff. And it’s interesting to step back and let other people curate and see what their choices are. I find these sorts of things really, really interesting from a collector’s point of view. Sometimes they pick stuff and I can’t even remember that we did it! We were flat out and you tend to forget exactly what you were doing.

Some of the selections are full blown, “written and produced by Stock Aitken Waterman” and then you have things like The Blow Monkeys, which just had Phil Harding mixing it.

The Blow Monkeys is of particular interest, because I was actually involved with Phil on that one. So, Jack Stevens, who was the A&R guy at RCA, as it was then, he asked me to do this for him. In those early days, when Phil had only just come over from working at The Marquee, I’m trying to get him established as a mix engineer and as a mixer; it was still very much the case that we had fingers in all the pies, because that Blow Monkeys track is very early. [released in Feb 86]

The other interesting thing about this particular compilation is the PWL branding. Over the years, there’s obviously been lots of “Best of Stock Aitken Waterman” type compilations but it’s quite interesting to it rebranded as PWL, and I guess you must be quite happy about that?

Extremely happy, because lots has changed over the years, obviously, and things move on, but the logo and the company has always remained with us. It’s Pete Waterman Limited, and if it’s got my brand on it, you know that I’ve approved of it. The Stock Aitken Waterman brand is Stock Aitken Waterman, but PWL is the record company and we’ve always treated it differently.

PWL was such a multi-faceted empire, really, at its peak and there were so many different elements to it. Obviously, the record label aspect came a little bit later on…

And we never wanted it…

That’s right… But how did you manage to keep track of the business side of things, because there was so much going on, wasn’t there? It must have been a bit of a challenge?

Yeah, but it’s like that famous saying, “if you want something done, ask a busy man”, you know, and also, if you’re as immersed as we were in it, you become brilliant at it. I was literally living this; seven days a week, certainly 16 to 18 hours every day. I was focused on what was going on, whether it would be PWL or Mike [Stock] and Matt [Aitken], or whether it be the other mix engineers, or [late night British Dance Music Granada TV programme] The Hitman and Her… My whole life was surrounded at that point, by music. And I had a great team around me, whether it be in the studio, in the offices, or at Granada; we had a great team. So they made it easy because they’re giving you solutions, not problems. Every time you make a record, you make a problem. “How do I get this on the radio?” “How do I get this on TV?” So you know there’s a problem, but what you’re looking for is solutions.

Every time you make a record, you make a problem

Pete Waterman

Your passion for music is well documented, but the business side of it, managing and motivating people… Where did you learn all those skills?

As a DJ, through Mecca. In those days, you weren’t the DJ that people think of today. I mean, you ran the ‘kids sessions’, as they were called, which meant people up to up to 18 years old. You did everything, you cleaned the floor, you checked the coats, you changed the toilet rolls in the toilets, you changed the towels – you were in charge! You hired the security staff and said, who came in and didn’t come in. At the end of the night, you went to the door to see the receipts of how many people had come in and the reason for that was you either reached your bonus, or you didn’t. And if you didn’t regularly, then you got pulled into the manager’s office and were asked “What are you playing? You’re not entertaining the crowd”. And we all go through that period; as a DJ, you can’t always be be on it. Sometimes you do back the wrong horse. For example, when Motown left Detroit to go to LA that gave me a real problem. Because I could play any Motown record when they were in Detroit. When they went to LA, and they started making records like The Temptations’ ‘Papa was a Rollin’ Stone’, I couldn’t play that record. I couldn’t play James Brown. My audience just didn’t want that heavy funk. They were used to that Northern Soul, R&B, uptempo boy-and-girl stuff. So the first thing you do as a DJ, is you revert to oldies… I’ll just take a couple of oldies in. And it works, but it only works for certain time because, after a while, the old has become boring, because they’ve heard him that too many times. And it’s at that point, you think, Oh, my God, I’ve got to do something quick here. I’ve gone from 1200 to 1300 kids on a night down to 400 and I’m still falling. And any minute now the manager’s going to come to me and I’m going to lose my job. So then you focus on the music. You really do, and you think, what am I missing here? So that’s where my training came from; watching the crowd, watching what worked and what didn’t work.

When you started to become successful in the mid-80s, you didn’t leave all that behind. You were working in a record shop, you had a radio show, you were in the clubs doing The Hitman and Her and all that. So you recognised that it was important to stay in touch with what was going on.

Oh yeah. I think it’s true to say and in hindsight, I probably kept the brand alive for years longer than anybody would have normally done, because I stayed with the roots. We didn’t get into [working with] American artists. Recently, I was talking to one of my contemporaries at the time, and they were paying producers $100,000 per track. Well, we were charging £500 a track! So it would have been very tempting, if somebody said, I’ll pay you guys $200,000 per track – come to the States. You think “We’ve made it”. But then, to me, you’ve completely changed what you’re doing. I’d had that experience with Rick Astley, and I was never gonna have that experience again.

I was gonna ask you about that because, I don’t think it’s a nuance that the man on the street really recognises; they just think all these all these records were ‘Stock Aitken Waterman’ but of course, Rick was signed to RCA, wasn’t he? So he had that relationship with a major record label, who were unrelenting in terms of making him do all that promotion and that seemed to be a big factor with him burning out and not being very happy. And you didn’t have much control over that because they’re the label…

Rick, Astley was a development deal. Very, very, very unusual in the record industry. They gave us £30,000 pounds to develop this artist, because I believed in him that much. I knew he needed time to grow and I didn’t want to just make a single; I wanted him to learn the studio business and feel comfortable. Now, no other company would have given me 30,000 quid. So you’ve got to hand it to RCA, they gave me the money in blind faith. I mean, I could have walked off with that £30,000 and never ever delivered an artist. After six or seven months they’re asking “what’s going on?”, because we still haven’t played them anything. So we bought them down into reception, and we literally did put a speaker and a microphone in the middle of reception. Julian and Peter came down from the RCA and Rick sang live ‘Ain’t Too Proud to Beg’ to a backing track. Everybody’s jaw dropped because they’d never seen anything like that before. You know, they were used to going into a rehearsal room and seeing a professional outfit. But you know, he was a tea boy, it was like “Rick just pop out here, will you? Just sing this song for these two geezers that have come down from the record company!”. But he did, and we still talk about it to this day. You would never do that to an artist now, but that’s how comfortable it all was. I don’t think either we, nor Rick, understood the treadmill that you then go on once you’ve got that hit. But the thing was, I realised [originally] in America, that Rick and ‘Never Gonna Give You Up’ was never going to be a hit, because he wasn’t a priority artist for RCA. Bill Tanner in Miami, who was the big DJ on the biggest station in America, he told me exactly why this would not be in America. He said to me “Pete, this is wonderful record, it’s number one on my station but it’s not going to be here in America”. “Why?” “Because it’s on RCA”. And had I not called Germany, because I knew the guy who ran the whole Bertelsmann Empire at that point, Monti Lüftner, things might have been very different, because I actually tried to get the record back for America. But he said “whatever you want, you’ve got”. So they were trying to get Patrick Swayze to number one with Dirty Dancing [‘She’s Like The Wind’] and they were pissed off that Rick Astley got there with ‘Never Gonna Give You Up’. I mean, they wouldn’t even allow us into the RCA building!

One of the songs on this compilation is Princess and ‘Say I’m Your Number One’, which is a brilliant, early track. But that was put out on Supreme Records, a label set up to release that song. What was the difference between doing that with Supreme and then what later became PWL because you were dipping a toe into the independent side of things with Princess, weren’t you?

Yeah. As I said earlier, we never want to be a record company, we just wanted to be producers and writers. So Nick East had done a fantastic job for us, with Hazell Dean and Divine. He was a promotion guy, who had got no money. So I went to him and said “Right, it’s time to set up your own record company”… “I haven’t got any money”… “Don’ t worry about the money. I’ve got a record. It’s Princess ‘Say I’m Your Number One’, I’ll put the money up, you form your record company”, which he did, and that was Surpreme. So that’s literally how that came about. So we gave him the record, rather than paying him, and he took it on his own label and took the profit off of that.

You could have done that yourself, but you just didn’t want to do that. You weren’t interested in getting into it?

No, because I wanted to keep it at arm’s length at this point. I had to go and borrow money to press the record for for Nick, because Nick didn’t have any money. Luckily I had a bank manager who had ears! He heard the record and said “how much do you need? You got it”. I walked away with £25,000 but with no security. I paid it back in about a month, but that was how we operated in those days.

One of the things I read, I think it might have been in Phil Harding’s book [‘PWL: From the Factory Floor’], was that you turned down the Pet Shop Boys, and ‘West End Girls’. Tell me the story about that?

I didn’t turn the Pet Shop Boys down, I turned [the group’s manager] Tom Watkins down. Tom Watkins is the only guy that’s ever ripped me off in the business and I always said, I wouldn’t work with Tom. It’s ironic that Tom Watkins, at the end, pinched Phil [Harding] and Ian [Curnow] off me. But I’m quite a moral guy when somebody rips me off. You think “that’s once, you don’t rip me off twice”. I do regret it [to an extent] because I love Neil and I love the Pet Shop Boys. And God, do I wish I’d produced ‘It’s a Sin’ but that’s just history. But I didn’t turn down the Pet Shop Boys, I just couldn’t work with with Tom Watkins.

One of the things people will be hoping for, maybe with future iterations of this compilation, is some unreleased gems or rarities. Whether that will happen or not is another matter, but there’s lots of interesting things you’ve done, which haven’t seen the light of day and one of them was a remix of Elton John’s ‘Wrap Her Up’.

Oh, you know about that? [laughs] Wow. I forgot all about that.

It must have been disappointing to have done that, and then see it get rejected from the label, management or someone?

Well, I think, again, we are talking very early here. And the snobbery was unbelievable in those early years, and it wasn’t a shock to us, to be honest. I think people saw us as challenging; we were changing the norm and I think that we definitely saw this and people would say that you can’t work with these guys, because they’re dangerous to us as a label; they’re taking business away from us. Actually, I used to see George Michael [who sings on ‘Wrap Her Up’] most Friday nights in Haringey, in the clubs; we tested some early 12-inches in the same gay clubs that he was in, testing is his mixes, but I guess it’s incredible now to think we were renegades! It’s like the we were the Antichrist. “For Christ’s sake don’t call Stock Aitken Waterman!”

The snobbery was unbelievable in those early years… “For Christ’s sake don’t call Stock Aitken Waterman!”

Pete Waterman

But who would have commissioned that? Because it’s weird that it got commissioned but then never got released [there was a white label]. You think if someone’s commissioning it, then they’ve had had the okay to do it, but I guess not….

I think we had a particular sound, a really unique sound at that point. And if you then put Elton John and George Michael into that unique sound, maybe the artists or the management go “Whoa, wait a minute… it’s no longer Elton John and George Michael, it’s Elton John, George Michael and Stock Aitken Waterman, and that’s we’re not going to allow that”.

Wet Wet Wet’s ‘Sweet Little Mystery’ was another example, I think

Yeah, at this point, the management particularly, were getting very worried that we would dominate the artist. That happened to us when we worked with Judas Priest. Bill Curbishley [the band’s manager] was the first guy to openly admit to the problem. You know, it was the biggest hit we never had. I remember playing it to Jonathan King and he went nuts and personally called Bill Curbishley and CBS, and told them they had to release it, that it would be number one all over the world. And Bill Curbishley said, yeah, but it kills Judas Priest… We’re not going to sell belt buckles, and beer mugs with a band that’s number one in the pop charts. So that was a lesson… you go “got it”, but it’s still sad because the whole of the Judas Priest session was amazing. It was a different world for us, a different world.

But all these years later, is that ever likely to see the light of day? Have people mellowed? Do they think “it doesn’t really matter anymore”?

Paul, I don’t know. I do think it is slightly sad that you can’t make up your own mind, whether it’s the best ever Stock Aitken Waterman record, or not. It’s a different world now, but you know, they’ve still got their fans, and they don’t want to let their fans down. They’re doing the same as we’re doing, issuing unreleased stuff and whatever, so you’d have to ask them, really. I still play it to people and go “Look what happened when you put Stock Aitken Waterman with a rock band!” You’ve got an enormous rock anthem.

With Judas Priest it was the biggest hit we never had

Pete Waterman

What did it actually sound like? Did you take all the all the musicians off and replace them with drum machines and sequencers? What did you actually do?

I think it was the most interesting session we did because you are with a well established band, who are all fantastic players. We recorded it in Paris in this enormous recording studio with all the drums mic’d up and we thought “Wow, this is rock and roll!”. We didn’t take any instruments, because they had everything. A Linndrum machine, for a click track, is probably all we took, but when we’re in there, and we’re teaching Rob [Halford] and the guys how to play the songs, it just became a mutual love-in. It was like “You guys are amazing”… “No, you guys are amazing!” Matt’s rock tendencies came out and one of the guys said, “God, you’re an amazing guitarist”. So it was like, we were playing with them. Yes, we added electronic keyboards, but that was after we’d recorded them as a live band. I remember sitting down and saying “I’ve got this idea, we’re gonna record a Stylistics song” [‘You Are Everything’]. Well, you could have heard a cockroach fart, it was silent. There’s these big hairy geezers with tight trousers and bulging bollocks and here am I suggesting a Stylistics song? But they got it straight away and Rob was brilliant. I think we did it in about two takes.

That’s very interesting. I was thinking it would sound like typical Stock Aitken Waterman production.

No, we became Judas Priest! [laughs]. They became Stock Aitken Waterman and were all interested in the technology but we weren’t interested, we wanted to get the guitars out! The whole thing got reversed.

Oh, well, we can keep our fingers crossed that it might surface one day, officially.

Yeah, absolutely.

You recorded Paul McCartney’s vocal contribution to ‘Let It Be’, the Ferry Aid single. Was there ever any conversations about working on other songs or an album, with Paul?

Indirectly. [long pause]. You can’t really work with your heroes. McCartney, to Mike, me and Matt was [another] stratosphere. So you are in awe, no matter what they do. You’re in awe. And so, when we did work with him, he was absolutely brilliant. He’s lovely to work with, but he wasn’t used to being produced. And we soon realised that. And I was the one that had to go in as the old Beatles fan and say “That’s great. Let’s go home”. And he’d be like “No, I can do it better”. “No, no. Let’s go home”. But the lovely side was that Linda and I became really good friends. So Linda used to ring me up because Paul would say, “I’ve got to talk to Pete Waterman because I’ve got to change that vocal”. And she’d say, “Pete’s the producer, it’s fine”.

Why was he unhappy about his vocal?

He was out of tune. He’d got emotional, and he’d gone slightly out of tune. But to me, it’s the part that makes the record, because you’ve got McCartney cracking up with emotion. But he’s a perfectionist, which is brilliant. So there we are, as fans, hearing Paul McCartney as he was in the 60s, it’s like, “Wow, this is Paul McCartney”. But he [wants to be] modern. He’s trying to make better records than Band on the Run, although you ain’t going top Band on the Run! So here’s this amazing guy but we’ve caught on tape this little bit of an historic moment of Paul McCartney. And Linda and the family recognise it straightaway. He was still calling us when it had been number one for four weeks, saying he could do it better! So, yes, there was this period where Linda said to Paul, you need you need to work with these guys because they’re fresh and they will task you to do things differently. But I don’t think we could have ever produced Paul McCartney, because we’re too big as fans.

Paul McCartney was absolutely brilliant to work with… but he wasn’t used to being produced

Pete Waterman

Let’s talk about the 12-inch mix, because obviously PWL Extended: Big Hits and Surprises is a collection of 12-inch mixes. At the beginning, the mixes were all about clubs and engaging with a club audience, but did that change over time and it became more about selling product and selling multiple 12-inch singles every time you released a song?

I think if you go back to the early days with Agents Aren’t Aeroplanes and The Blow Monkeys, we were the 12-inch kings. [At that point] we were not getting work from other people but we realised that you could make enough money by selling 12-inch singles to make another record. So we specialised in 12-inch mixes, particularly on that Agents Aren’t Aeroplanes record. We knew we weren’t going to have a hit, but all we had to do was raise enough money to make the next record. It was the same with Hazell Dean, and that kept us going. We weren’t rich by any stretch of the imagination, at this point, but we had enough money to make the next record. I remember when we got called in to do Dead or Alive, when we were doing the contracts, I demanded a royalty on the 12-inch. Well, major record companies treated 12-inches like promos – they [virtually] gave them away. So they just didn’t care. They put in my contract that I got paid on 12-inch records. The band didn’t get paid on 12-inch records. So when suddenly that 12-inch, worldwide, had sold over a million they had a problem because the band wasn’t being paid and Stock Aitken Waterman were. So that’s why these 12-inches are important to us. They weren’t part of our marketing strategy, they were part of what we knew was needed. It was part of our art form, if you like

Would you sometimes work on the 12-inch first and then maybe edit it down for the seven-inch version?

Yeah, quite often. Certainly on ‘Roadblock’ we did. Actually, Princess started off as a long version which we shortened. Things like Kylie and Jason were never like that but Sigue Sigue Sputnik was made in a 12-inch form and with Lonnie Gordon we always made as 12-inches and edited down.

Getting back to PWL and the actual record label part of it, you would have had this interesting relationship with the majors because, they were your clients, so you’d produce music for Dead or Alive for CBS and do remixes etc. But also they were also your rivals, weren’t they? For example, when EMI did the spoiler thing with Nat King Cole and Rick Astley [EMI released the original of When I Fall In Love while Rick’s cover was in the charts]. So they could be complete bastards…

They were complete bastards.

But you’re having to work with them and maintain some kind of relationship…

Yeah, but we just carried on. We knew that they were threatening their A&R guys. You know, “if you’re a naughty boy, we’ll send you to Stock Aitken Waterman”. That’s worse than sending you to Coventry! You know, nobody will ever speak to you again. Yeah, we knew that, but it didn’t worry us.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but Mandy Smith might have been the first PWL record…

It was, yes.

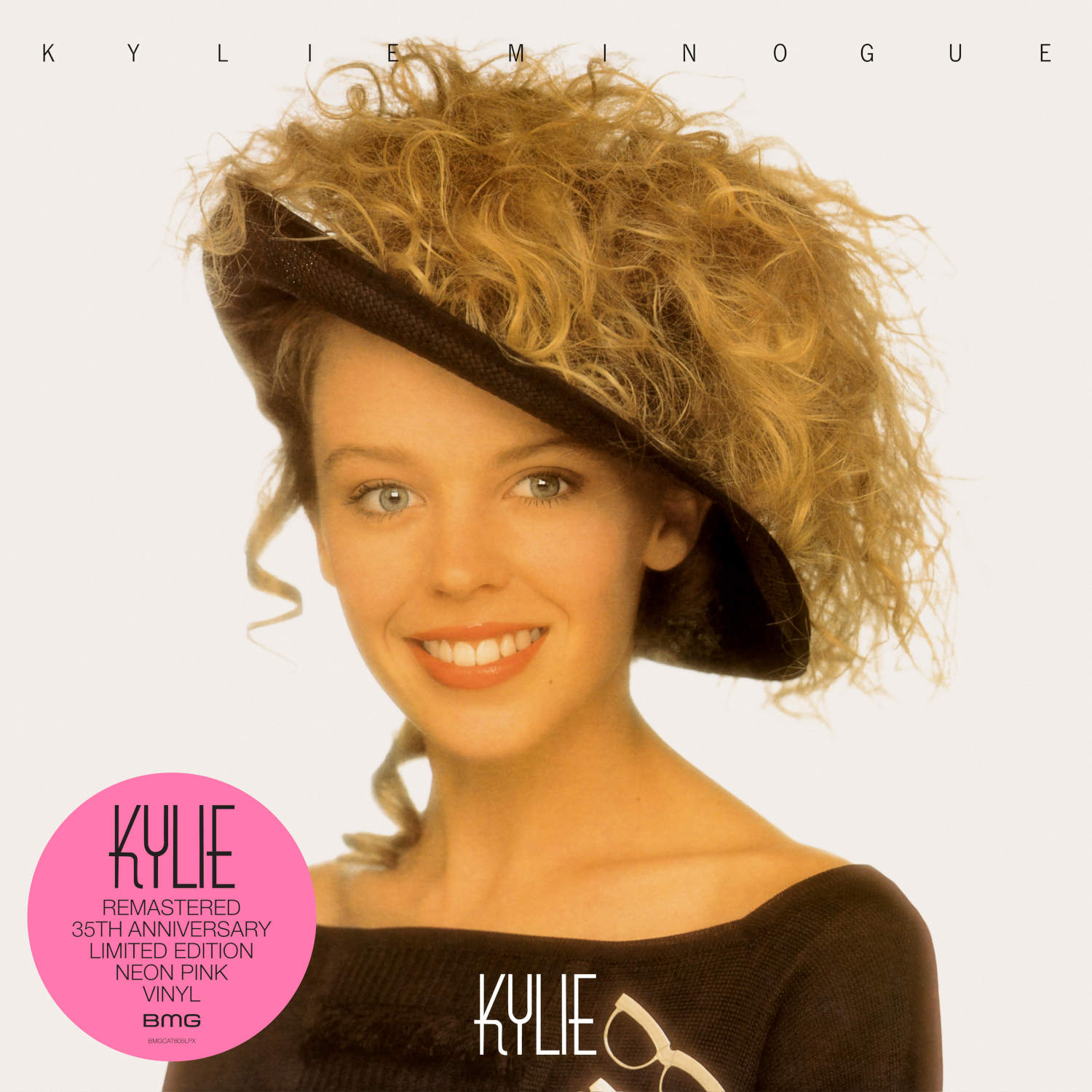

And then obviously, Kylie was the big one that followed. It seems incredible that no other label was interested in Kylie, at the beginning. Is that just what you were reflecting on earlier, just a Stock Aitken Waterman thing…

Yes. Yes! And I was offering ‘I Should Be So Lucky’ for £1200, by the way, when most people were paying £15,000 pounds per track. But nobody took it. Nobody. I went to a music conference in America and that’s where Steve Mason who owned Pinnacle distribution, talked me into putting it out on PWL. “This is a hit, put it out yourself!” That’s how that came about. I didn’t want to do it.

Why didn’t Matt and Mike come in with you on the label? Because ultimately, it’s PWL and not Stock Aitken and Waterman Records. It would have seemed the natural thing for the three of you to do it as a joint enterprise.

They didn’t want to do it.

Why not?

They just didn’t want to. You have to ask them, I suppose. They didn’t want to invest, they didn’t believe in the artists… That wasn’t what they did. They were writer-producers. Matt and Mike took their royalties and they didn’t have to pay the staff, I paid the staff. So what I did with my company, PWL, was up to me. If they’d have wanted to, at any point, they could have come in and said, well, we’ll put some money in with you.

So what extra burden and workload did having the label bring? I know you used to sleep in the vocal booth in the early 80s, which is kind of crazy.

Yeah. It brought the added load of more staff, who all had mortgages to pay. You start with four or five staff and then suddenly, you’re up to 12 to 14 staff. These aren’t the actual figures but it’s like you’re paying £3,000 a month in salaries, and national insurance contributions and suddenly you’ve gone to £25,000. That’s a whole different ballpark. So it wasn’t about me living in a flat, it was about me paying the wages every month, and not having the bank pulling everything from us.

So it would be typical business cashflow-type issues that would you’d be faced with?

Yeah. Cashflow problems in record industry was how the majors control the independents because you always had a cash flow problem, because you didn’t get paid for six months and 90 days. Take Rick Astley. We had the number one record in the world and Barclays Bank was chasing me for an overdraft of £5000. I probably had four million pounds sitting out there all the way around the world and I was I was getting threatened with bankruptcy for a £5000 overdraft. That’s just the way it worked. So you’re constantly changing banks, and you’re constantly having to deliver the wages. I wouldn’t have changed it for the world, by the way, but it’s interesting looking back

And I guess once PWL was set up, every new artist would be automatically added to the roster to make it work. You had to scale it up, didn’t you?

We did it and we didn’t, because I didn’t sign Sonia to the label. I signed Sonia to Chrysalis.

Why did you do that?

I wanted some of the pressure taken off. It’s the same with Stock Aitken Waterman [with songs like ‘Roadblock’]. I licensed that to A&M, because it was just too much pressure, at that point. I didn’t want to take any more staff on. We couldn’t cope with Kylie and Jason, let alone Stock Aitken Waterman, Sonia and all the rest of it. Most major record companies can only deal with three big artists, so trying to deal with five in a little company? Forget it!

When Kylie came along, it felt like, the start of a new era.

It was

Some people are always going to criticise Stock Aitken Waterman, and a lot of it is snobbery, as you say, but do you accept that, come 1988-89, things changed a bit and that you lost that dancefloor credibility you once had and it became more about just having hit records? It no longer mattered about being cool anymore? Where was your mind at? Were you even aware of a shift going on?

Oh, yeah, I think so. We’ve just had a conversation about how tough it was to pay the bills, and no major record company was giving us any work. And suddenly, we’ve got an artist earning a quarter of a million pounds a week [Kylie]. If someone’s offering you more money, you say “Fuck you, pal. I’m off over here”. This wasn’t me thinking I’ve got to be credible… bollocks [to that]! I’ve got to pay the wages here; I’ve got 32 staff. I don’t need the bank calling me every three weeks and asking me to pay in a cheque. We’ve got no credibility, anyway, so we might we’ll take the cash. We’ve won the lottery, so do I ring up the Lottery and say “sorry, I don’t want it”? Bollocks ! I’m taking the money…

I get it. But it’s hard to look into the future and kind of see where things were leading you.

Absolutely. But at that moment in time, you can’t look into the future. Yeah, I can look back now and say, if we sold Kylie, after the second album, which we could have done, to EMI for a lot of money, we’d have gone back to being what we’d done before. But we didn’t. Because we’d become a massive organisation at that point. Now, do I regret that? Yes, I can look back and say, that’s when we should have said “Right. Off you go over there. You set yourself up. We’re going back to basics”. But it was out of my hands by that time, because it was such a big organisation.

Was the aim always to have a hit single? Did you ever worry about the artist, in terms of ‘here today, gone tomorrow’? I’m thinking of the Reynolds Girls of this world. Did you ever feel a sense of responsibility around how then tended to get discarded – one hit and they’re off?

No, no, no, that’s absolutely the wrong way to look at it. Yes, I took responsibility for all my artists. And with The Reynolds Girls, I’m glad you picked them, because that wasn’t my decision, that was their dad’s decision. In fact, if you look at Hazell Dean, you can see our loyalty because we stayed with with Hazell right to the end. There was a problem in that she wasn’t selling records, but we stayed there; we didn’t drop her. I think 99 percent of the time the act wanted to drop us, or there was a situation were I didn’t agree [with something]. It’s like, if you want to go, away you go. When Rick wanted to go to RCA, I wasn’t gonna stand in his way. We’d been mates for a long time. It was like, if that’s what you want, Rick, off you go. When we were responsible for the artist, we never ever treated an artist as a one off single.

Thanks to Pete Waterman who was talking to Paul Sinclair for SDE. PWL Extended: Big Hits and Surprises is out now. It’s available as two 12-track 2LP sets, a 24-track 3CD package or the limited edition SDE-exclusive 26-track, stereo-only blu-ray audio, available only via the SDE shop using this link or the button below (limited to 1000 worldwide).

TECHNICAL NOTES: This blu-ray audio requires a blu-ray player. It will not play on a CD player!

Compare prices and pre-order

Various Artists

PWL Extended Big Hits and Surprises - 3CD set

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Compare prices and pre-order

Various Artists

PWL Extended Big Hits and Surprises Vol 1 - 2LP vinyl

Compare prices and pre-order

Various Artists

PWL Extended Big Hits and Surprises Vol 2 - 2LP vinyl

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tracklisting

PWL: Extended Big Hits and Surprises Various Artists /

-

-

- AGENTS AREN’T AEROPLANES The Upstroke (Extended Version) 6:26

- THE BLOW MONKEYS Digging Your Scene (Phil Harding Remix) 7:39

- PRINCESS In The Heat Of A Passionate Moment (The Final Frontier Mix) 7:48

- RICK ASTLEY Never Gonna Give You Up (Cake Mix) 5:47

- STOCK AITKEN WATERMAN Roadblock (Extended Version) 8:08

- SAMANTHA FOX Nothing’s Gonna Stop Me Now (Extended Version) 7:01

- RICK ASTLEY She Wants To Dance With Me (Extended R’n’B Version)** 4:41

- SHOOTING PARTY Safe In The Arms Of Love (Phil’s Extra Beat Update) 7:18

- CAROL HITCHCOCK Get Ready (Original 12″ Remix) 8:28

- KYLIE MINOGUE I Should Be So Lucky (Extended Mix) 6:05

- JASON DONOVAN Nothing Can Divide Us (Great Scott, It’s The Remix) 6:08

- SIGUE SIGUE SPUTNIK Success (Balaeracidic 12″ Mix) 7:00

- KYLIE MINOGUE Hand On Your Heart (The Great Aorta Mix) 6:24

- JASON DONOVAN Too Many Broken Hearts (Extended Version) 5:46

- SONIA You’ll Never Stop Me Loving You (Extended Version) 7:59

- KYLIE MINOGUE Better The Devil You Know (The Mad March Hare Mix) 7:07

- LONNIE GORDON Happenin’ All Over Again (Hip House Mix) 5:37

- PRINCESS Say I’m Your Number One (Tony King’s 5 Years On 12″ Mix) 6:52*

- HAZELL DEAN Better Off Without You (A Touch Of Leather Mix) 7:09

- PAUL VARNEY If Only I Knew (Hurley’s House Mix)** 6:26

- THE TWINS All Mixed Up (12″ Mix) 6:00

- KYLIE MINOGUE What Kind Of Fool? (Heard All That Before) (12″ Master Mix)*** 6:50

- WEST END FT. SYBIL The Love I Lost (Unrequited Mix) 6:35

- BOY KRAZY That’s What Love Can Do (Club Mix) 6:47

Bonus tracks (exclusive to the SDE blu-ray audio)

- STOCK AITKEN WATERMAN SS Paparazzi (Dave Ford’s Acid Mix)* 4:49

- DELAGE I Wanna Shout About It (12″ Mix) 6:46

-

Interview

Interview

By Paul Sinclair

32