The Dream Academy’s Nick Laird-Clowes talks to SDE

Incredible stories from a life in music

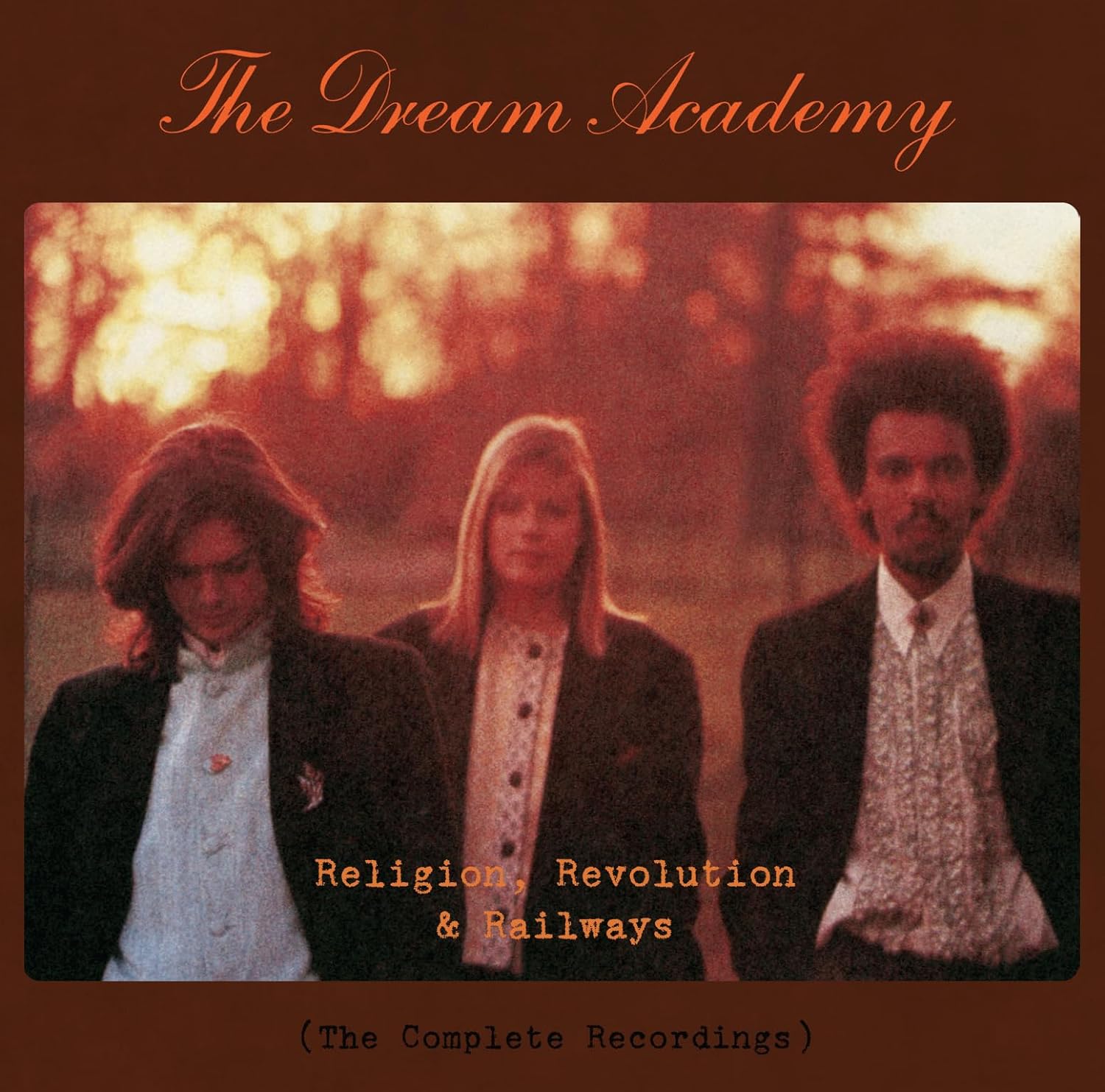

Pastoral art-pop band The Dream Academy – singer / guitarist and songwriter, Nick Laird-Clowes, multi-instrumentalist Kate St. John, and keyboardist / songwriter, Gilbert Gabriel – had a hit on both sides of the Atlantic with their haunting and ethereal 1985 debut single, ‘Life In A Northern Town.’

This month, the complete recordings by the trio, who were signed to Warner Bros and had a close musical association with David Gilmour – he co-produced two of their three albums – are being released by Cherry Red Records in a 7CD box set called Religion, Revolution & Railways.

The collection, which includes the three studio albums, The Dream Academy, Remembrance Days and A Different Kind of Weather, as well as B-sides, rarities, demos and remixes, has been carefully compiled by Laird-Clowes, who was involved with the remastering, artwork, photographic material and the in-depth liner notes.

SDE spoke to him about the project and his early influences, and he shared his memories of working with Gilmour, Marc Bolan, Hans Zimmer, Johnny Marr, Peter Buck, Lindsey Buckingham and Brian Wilson…

SDE: Let’s talk about the box set – Religion, Revolution & Railways. The Dream Academy made three studio albums, but the new collection is a 7CD set – it’s very extensive…

Nick Laird-Clowes: There’s a lot – the whole thing took a long time – about a year. After 40 years, it’s amazing to have people like your work and that’s it’s still being played and still around, so I wanted to take it really seriously. We took so much trouble over our three albums – we were meticulous about everything, like the mastering. So, for the box set, I said to Cherry Red, ‘if you want to do it, I’ve got to be involved,’ and they said they would love me to be.

We [originally] wanted to be signed to Cherry Red – we sent them all our demos, but they turned them down, so now it’s perfect.

How does it feel to finally have everything in one place?

I feel thrilled – I’ve got it the way I wanted. I’d always wanted a box set. In 2014, Rhino said they would do a double ‘best of’ but they wouldn’t do a box set.

It was a lot of work – a major undertaking. It’s lovely because now all the credits are right, so with any future thing that comes out I can go back to that – you want to credit everybody that was involved at the time.

You had to go into the Warner Bros archives to find some of the rare material you’ve included, didn’t you?

Yes – I’m a completist of our work. I’ve got all the cassettes from the beginning – from the earliest days of our demos. I knew where quite a lot of the stuff was – I found a lot of different things – but I didn’t know what Warner Bros had in the archives. Somewhere along the line, the archives were digitised from tape, but some of the digitising wasn’t good enough, so I had to find other sources.

I suddenly remembered that we’d made backing tracks of our second album… The first album was done almost like demos and then I took them to David Gilmour who fixed them – we probably spent three months doing that and mixing them.

The next album we did with Hugh Padgham, who was at the top of his game. He said he thought we should use some other musicians and not as many machines as we did on the first album. So, we said, ‘okay’. He’d worked with Peter Gabriel – we were such big fans of Gabriel at that point – and he said we could use Larry Fast to program a synthesizer to make incredible sounds, and the brilliant drummer, Jerry Marotta – he was a legend. You just don’t hear backing tracks like that anymore – now you make everything in your bedroom or on a computer.

Hans Zimmer programmed the Fairlight on some of the songs on the second album, Remembrance Days, including the track ‘Indian Summer.’

Yes – before he ever went to Hollywood! He had a studio in Fulham, with a huge Moog synthesizer wall. We asked him if he could make the waves on ‘Indian Summer’, and he said, ‘of course I can!’

You said you’re a Dream Academy completist, but was there any stuff in the archives that you’d forgotten about, or any rare material you discovered?

The songs ‘The Last Day of the War’ and ‘These Walls’ – I think ‘These Walls’ was one of the first things Gilbert and I ever wrote, along with ‘The Edge of Forever’ and ‘Test Tape No.3.’ There’s also a demo of ‘Doubleminded,’ which was a song we saved and didn’t use on the first album – we used it on the second. It was beautifully produced by Padgham, but we did a demo in David Gilmour’s studio, with his brother, Mark, engineering it. We set up and recorded it very quickly – some of those songs we used as B-sides and some never came out – they’re on the box set. We had to master them three times to get them to sound as brilliant as they could.

I don’t want our music to sound like it’s from the 21st century – it’s made in its time, exactly the way we wanted to make it, and I want it to sound exactly like that.

Nick Laird-Clowes

There’s now a feeling that you have to master something to sound great on Spotify, but I don’t want it to sound like it’s from the 21st century – it’s music made in its time, exactly the way we wanted to make it, and I want it to sound exactly like that. That was a lot of work. If you hear a Nick Drake record, you don’t want all the bass pumped up – you want to hear it as it was.

You used Tony Dixon at Masterpiece Masters to do the mastering…

Yes – he was great and very sympathetic.

Discs 4 and 5 have alternative versions, B-sides and rare songs on them. ‘Girl In A Million (For Edie Sedgwick)’ is a great track and really stands out. It has a melancholic and autumnal feel…

That’s music to my ears – that song is a real favourite of ours. I wrote the words for Edie Sedgwick – it’s the quintessential Dream Academy sound. It was an early song and we played it to David Gilmour, but he said ‘no…’. We said, ‘What? Come on – it’s fantastic!’ He said we already had lots of beautiful things on the first album…

It’s been a long time… and, as a musician, you just keep on going forward through life and onto the next piece of music you’re working on, but when I went back and listened to all this stuff, I thought the three of us were so lucky to meet and we had a sound – I’d always wanted a sound.

With my first two bands [Alfalpha and The Act], I had record deals, but it didn’t happen – I realised I was just copying [other acts]. You’ve got to copy to learn, but then you must discard the copying and find your own sound.

Gilbert was such a perfectionist with chord shapes, but when Kate joined the band and she added her touch to that, and she started singing… Oddly enough, it was pretty indie and punk in its own way, even though the music was beautiful, because we were doing something we really believed in and we were on our own. It wasn’t that we were trying to be the best in the world – we were doing our version of music that we loved, rather than going with what was the thing at the time, which was basically white-boy soul.

You had a distinctive sound – acoustic guitar, oboe, cor anglaise and strings played on a synth…

Exactly – in a way that was harking back to an earlier period of music. It was sort of pastoral but other things too – Gilbert was really interested in things like Steve Reich and people I hadn’t heard of. He made me listen to Ravel and Erik Satie when I was about 22. I was so thrilled with The Beatles and post-Beatles work, but Gilbert really opened me up, which helped me find a new voice.

Talking of The Beatles, there’s a version of ‘Things We Said Today’ that’s included on the box set. It was a B-side and it’s your own take on the song – you’ve slowed it down and stripped it back. It has a slightly eerie sound and a synth on it…

I almost thought, ‘should put we put it on?’ but it was a B-side… I hadn’t heard it since it came out – things were moving so fast at that time. We just stuck it on as a B-side – it so live-sounding. We just stood in the room and played – it’s a live vocal and guitar, with Gilbert playing keyboards. We’re playing to a drum thing. I thought it held up well because it wasn’t a copy.

I bought the guitar that was on the front of Bryter Layter for a hundred quid

Nick Laird-Clowes

You mentioned Nick Drake earlier. He was a big influence on you, wasn’t he?

That’s true, and Joe Boyd had produced the album I did with The Act – he’s still a great friend. Those Nick Drake albums didn’t sell anything [at the time]. If I played people Bryter Layter, they’d never heard of it. I even bought the guitar that was on the front of Bryter Layter when he was still alive. I bought it for a hundred quid – I was 16 and I worked in the RCA record factory for the summer to get the money to buy it.

Have you still got it?

Yeah – it’s right here.

When you were 13, in 1970, you ran away from home to go to the Isle of Wight Pop Festival, didn’t you?

Yes – it changed my life. I’d seen The Beatles when I was seven – Kate had too. I started to go and sit outside Apple, and I was invited in. I didn’t meet The Beatles – just the secretary – but I’d written to John and Yoko, and they’d written back.

I was so useless at school, and I was rowing with my father all the time. Like so many people, music was guiding me and the people who were making it could turn you on to amazing philosophical ideas and other music. I’d been thrown out of school.

My sister and I bought tickets for the Isle of Wight, but my parents said I couldn’t go because I was 13. I had an elaborate ploy to make them think I was staying with a friend, and I ran off – I had no money. I got on the train and met people – when we get there, the first band I saw was The Doors. We didn’t have a tent – the people I met on the train said we could stick with them, as they wouldn’t be sleeping much – ho ho ho. It was only a year after Woodstock – The Who and other people were playing their same sets. It was mind-blowing and it changed everything. I knew I had to do it, but my father never really spoke to me until The Dream Academy were successful – he was suspicious, and he thought I’d end up in jail.

Through running away from home, I met Jeff Dexter, who was a great DJ – he asked me to become his assistant. We did four nights with Led Zeppelin when they’d done ‘Stairway To Heaven’, and we did the Hyde Park concert with Roger McGuinn and Toots and The Maytals. It stemmed from me following the only thing I liked, which was music – that led to everything.

Did you grow up in London?

Yes – in Notting Hill Gate. It wasn’t the Notting Hill of the Richard Curtis movie – it was an edgy place where other children didn’t want to come because it was rough. It was great – the older hipsters were on the street and all around.

In the ‘70s, when you were in the band Alfalpha, with brothers Andy and Sam Harley, you sang backing vocals on the T.Rex album, Dandy in the Underworld…

Yeah – on the songs ‘Dandy in the Underworld’ and ‘Crimson Moon’ I think. When I was 16, I started playing every single day and writing songs. Jeff Dexter started critiquing them. When I was 17, he said that I needed to put a band together, and he’d met two brothers… We started working together – by the time I was 19, Jeff started managing us, and he also worked with Tony Howard, who was Marc Bolan’s manager. I was a huge fan of Marc and he asked us come into the studio – it was amazing. He was very punk in his ideas. If I said something wasn’t in tune, he’d say, ‘It’s not whether it’s in tune, it’s about attitude’. He said that the energy you put into it was the energy you’d get back in the recording – it was brilliant.

After Alfalpha, you had a band called The Act – you advertised in Melody Maker for a keyboard player and Gilbert Gabriel answered, which is how you ended up working with him and forming The Dream Academy. What kind of music was The Act?

It was power pop. Alfalpha was our attempt at being Crosby, Stills and Nash or America, with three-part harmonies – it was acoustic. We split up – we made one album on EMI. I went to New York for the first time ever – a girlfriend lent me the money and we went together. Punk and New Wave had exploded. I said, ‘My God – this is where it’s at’.

I came back and formed a band with an electric guitar – then Mark Gilmour joined as the other guitarist, and we had Derek Adams on drums and Sam Harley on bass. We were making a combination of Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers and Elvis Costello.

It was all great until I met Costello – we’d been in the Melody Maker that week, with R.E.M., who were a fledgling band. Costello said: ‘What do you do?’ I said, ‘I’ve got a band.’ He said: ‘What’s it called?’ I said: ‘The Act,’ and he went: ‘Oh, are you the ones that do me, or are you the ones that do The Byrds?’. The band that did The Byrds was R.E.M. I said we were the ones that did him and it was so embarrassing. I had to find my own voice.

Gilbert joined on keyboard – we went on a little tour of Spain, but the gigs were cancelled, we shared a room and played each other music that we loved. We started writing together – I’d always written alone – and it was completely different. He was very motivated and still is – he would come up with ideas all the time and push to get us further. In the end, we outgrew the band and started working on our own, playing gigs with backing tracks.

That was as the duo, Politics of Paradise, wasn’t it?

That’s right. Once we met Kate, she said she knew some really good classical players who loved pop and rock – she was at college with them and she introduced us to them, people like Adam Peters and Ben Hoffnung, who joined. Suddenly we had a big band – there were about eight or nine of us and we played in a club in a disused casino under MI5. It was insane! Tom Dixon, who ended up running Conran, ran the club – he had a welding torch on stage and he’d bang metal when we were singing ‘Life In A Northern Town.’ It was the first moment we knew that song had legs.

Let’s talk about ‘Life In A Northern Town.’ A lot of people think it was written about Nick Drake, but it wasn’t, was it? However, you did dedicate it to him…

It was our first single and we each dedicated it to someone we loved who influenced us.

You wanted to write a song with an African-style chant, didn’t you?

Yes. We were writing songs all the time – three times a week, I’d go to Gilbert’s in Southgate, which was miles from where I lived. I went to see him one day – we were sat in the kitchen and we had this idea. We went next door – Gilbert played a guitar with two or three strings, and he helped me work out an arpeggio on my guitar, then he moved his finger up on his guitar and that was the African chorus thing.

When I got home that night, my parents were in bed – I sat in front of the television with the sound off and I had my cassette player, a guitar and a hash pipe. smoked the hash pipe, listened to the cassette of the things we’d done in the day, and I started free forming lyrics. But I couldn’t remember the African chorus, so I added something that we’d done when I was in The Act.

The next morning, I listened to what I’d done and I thought ‘that’s good – I’m going to do another verse’, and I wrote the third verse. I took it to Gilbert and Kate – I’d only met her two days before. One of the first things she ever did was to play it with us – it suddenly opened up and had this sound and atmosphere. It was a whole other world, but it didn’t have a chorus – just the chant.

I’d met Paul Simon years before in New York, when I was in The Act. Me and my girlfriend went for dinner with him and his manager. He asked me what I did and I said I was a singer-songwriter. He went: ‘Really? Are you? Why don’t you come to my house tomorrow and play me some stuff?’ So, I went and I played him the album by The Act – he said it was good, but that it would never be a hit. I said: ‘I think you’re wrong!’ but he said: ‘I’m not!’

Anyway, the next time he was in London, he called me up and I went to see him. He played me his new album, Hearts and Bones, on an acoustic guitar, which didn’t even have the right strings on it, and I played him ‘Life In A Northern Town’, which had the ‘Ah-hey-ma-ma-ma-ma’ part in it. He dropped me home in his car and he asked me what I was going to call the song? He said it if was called ‘Ah-hey-ma-ma-ma-ma’ no one would know what to ask for in a record shop! I told him it was called ‘The Morning Lasted All Day’, but he said, ‘oh no, no…’ I had these blue notebooks that I wrote everything in, so I said what about ‘Life In A Northern Town?’ And he said, ‘that’s a great title for a song’.

So, I went in the studio and over the the mix we’d done with David Gilmour, I started singing ‘life in a Northern town,’ and I did some ad-libs. It took a lot of stages to complete it.

A lot of record companies turned the song down…

Geoff Travis [at Rough Trade] turned it down, along with everyone else, but he took it to America and played it to some record companies. When he came back, he said both Sony and Warner Bros really loved it, and then it all kicked off. When we got to New York, we were the new thing – it was extraordinary. We were an American signing – Warner Bros was like the biggest indie company in the world. They signed us for three albums and said, ‘Don’t try and make a hit record with your first album’.

‘Life In A Northern Town’ changed our lives – Warner Bros heard it and they got it, which was amazing, because it was coming from an art place. We weren’t trying to make a hit single, that’s for sure.

It got to number 15 in the UK singles chart and number seven in the US…

That’s right – according to Billboard, it was the highest played record of that week, and it should’ve gone to number one, but something stopped it. That’s how it goes in America.

Everywhere we went we’d hear it – in the airports… It was mind-blowing and our time had coincided with the birth of MTV, which was fantastic.

You had some great musicians play on your albums, including Johnny Marr, Peter Buck, Pino Palladino, Lindsey Buckingham and Guy Pratt…

I met Peter Buck through Joe Boyd, who was working with R.E.M. He was at a party around the corner from my house – I was so impressed, and I told him we were making an album with David Gilmour. He said he would come and play on it, so we set him up with David’s old Rickenbacker and it was brilliant.

Guy Pratt was in a band who used to play with Gilbert and I at the Language Lab in Dean Street – he used to come to my parents’ house and play bass.

For our second album, he’d been playing with Johnny Marr, who said he loved our version of ‘Please, Please, Please Let Me Get What I Want’ and would love to play on one of the songs on the album, but he said we couldn’t tell anyone because Morrissey would go crazy!

So, he was on anonymously at first. He arrived in a BMW, driven by Keith Richards’ roadie, with a stack of pizzas and, I kid you not, he was playing an electric 12-string, unplugged, in the back of the car. He was so cool, and he played until about six in the morning – he was absolutely incredible.

How did you come to work with Lindsey Buckingham on your second album?

Warner Bros was like a big indie family… I was mixing with Hugh Padgham, but we were disagreeing on all the mixes. I was always difficult to work with because I knew what I wanted but I didn’t know how to get it – it was very annoying for people, and, after having the hit, I was worse.

I played the mixes to Lenny Waronker [president of Warner Bros] and he said it didn’t sound like we were having a good time. I said we weren’t and he told me to stay there and mix it with the people who were working with Brian Wilson.

Lindsey Buckingham had seen us on Saturday Night Live, loved the band and wanted to do something

Nick Laird-Clowes

He also said Lindsey Buckingham had seen us on Saturday Night Live, loved the band and wanted to do something. We worked with him for a couple of weeks at his house, which was on the top of a hill – it was a total joy. He’s a mind-blowing guitarist and he’s a mind-blowing bass player. They were very dope-fuelled sessions… He was a very interesting individual and he split from Fleetwood Mac while he was working with us, so it was pretty intense.

At the same time, Lenny asked us to go and see Brian Wilson, who was in the middle of making his first solo album – we were asked to go in and help. He was sat at the piano, playing ‘Roll Out The Barrel’ for about 20 minutes – he was in quite bad shape and Dr Landy was there. The next day, Brian told me to go in on my own and I wrote a song with him, which was mind-blowing.

You’ve been a successful film soundtrack composer for more than 20 years, but do you still write songs?

I can’t help it. I’ve been doing it for so long – I started at 16 and I can’t stop. I came up with a lyric yesterday. I can’t believe I’m still doing what I love.

Thanks to Nick Laird-Clowes who was talking to Sean Hannam for SDE. Religion, Revolution & Railways is released on 23 February 2024 via Cherry Red Records.

Compare prices and pre-order

THE DREAM ACADEMY

Religion, Revolution and Railways - 7CD box

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tracklisting

Religion, Revolution & Railways: The Complete Recordings The Dream Academy /

-

-

CD 1: The Dream Academy

- Life In a Northern Town

- The Edge of Forever

- (Johnny) New Light

- In Places on The Run

- This World

- Bound To Be

- Moving On

- The Love Parade

- The Party

- One Dream

-

CD 2: Remembrance Days

- Indian Summer

- The Lesson of Love

- Humdrum

- Power To Believe

- Hampstead Girl

- Here

- In The Hands of Love

- Ballad In 4/4

- Doubleminded

- Everybody’s Gotta Learn Sometime

- In Exile (For Rodrigo Rojas)

-

CD 3: A Different Kind of Weather

- Love

- Mercy Killing

- Lucy September

- Gaby Says

- Waterloo

- Twelve-Eight Angel

- St. Valentine’s Day

- It’ll Never Happen Again

- Forest Fire

- Lowlands

- Not For Second Prize

-

CD 4

- The Love Parade (Remix) – US Single

- Please Please Please Let Me Get What I Want – Single

- Girl In a Million (For Edie Sedgwick) – B-Side

- In Places on The Run – Edit

- In The Heart – Japanese Single

- The Chosen Few

- Indian Summer – Single Version

- Hampstead Girl – B/V Mix

- Sunrising

- The Demonstration – B-Side

- The Last Day of The War (Pt 1) – Unreleased

- The Last Day of The War

-

CD 5

- The Day It Rained Forever – Unreleased

- Poised On the Edge of Forever

– B-Side - Test Tape No.3 – B-Side

- Bound To Be – Demo

- Things We Said Today – B-Side

- Doubleminded – Demo – Unreleased

- These Walls – Unreleased

- The Party – Acoustic Version 9 Living In a War

- Immaculate Heartache – B- Side

- House Of Heartbreak – Unreleased

-

CD 6

- Please Please Please Let Me Get What I Want – Instrumental

- The Love Parade – Instrumental

- Humdrum – Instrumental – Unreleased

- Power To Believe – Instrumental

- Hampstead Girl – Instrumental – Unreleased

- Here – Instrumental – Unreleased

- In The Hands of Love – B/V Mix – Unreleased

- Ballad in 4/4 – Instrumental – Unreleased

- Doubleminded – Instrumental – Unreleased

- Everybody’s Gotta Learn Sometime – Instrumental – Unreleased

- In Exile (for Rodrigo Rojas) – Instrumental – Unreleased

- The Demonstration – Instrumental – Unreleased

- In Suspendium – B-Side

-

CD 7

- Life In a Northern Town – Extended

- The Love Parade – 12 Mix

- Indian Summer – Extended Version

- Angel Of Mercy – 12/8 Mix

- Mordechai Vanunu – B-Side

- Love (Is Seven) – B-Side

- Love – Dreamstrumental

- Love – Dream House

- Love – Love Is 12

- Love – Whales in Love

- Love – Hare Krishna Mix

- Heaven – Pts 1 /2 – Unreleased

-

CD 1: The Dream Academy

Interview

Interview

By Sean Hannam

34