Wonderful Life: The 'lost' interview with Colin Vearncombe RIP

Last week, we heard the sad news of Liverpool-born singer-songwriter Colin Vearncombe’s death in a car accident at the age of just 53. Back in 2013, Vearncombe, aka Black, whose prolific career spanned four decades and is best known for his timeless classic song Wonderful Life, talked to SuperDeluxeEdition editor Paul Sinclair. We publish that interview here for the first time in tribute to a distinctively talented musician…

First, a little bit of backstory. It wasn’t so long ago that the SuperDeluxeEdition blog was a labour of love that I squeezed in around my day job. It was about as much as I could manage then just to keep up with writing new stories around forthcoming box-set releases. As I was still establishing it, even the record companies that had heard of SDE rarely offered me interviews with artists, and even if they did, I didn’t always have the time to take them up on the opportunity or had to squeeze them around other commitments (I conducted this interview with Stephen Street in my lunch break, in a busy open-plan office environment while freelancing as a graphic designer).

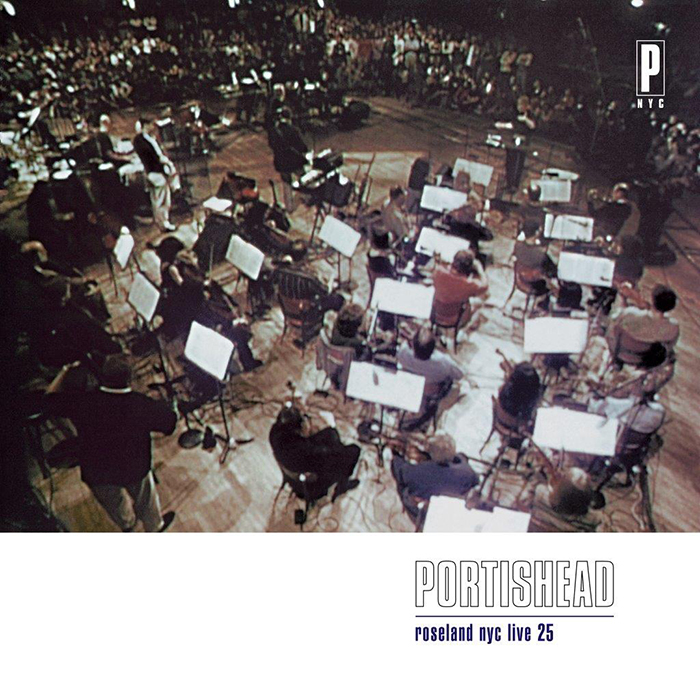

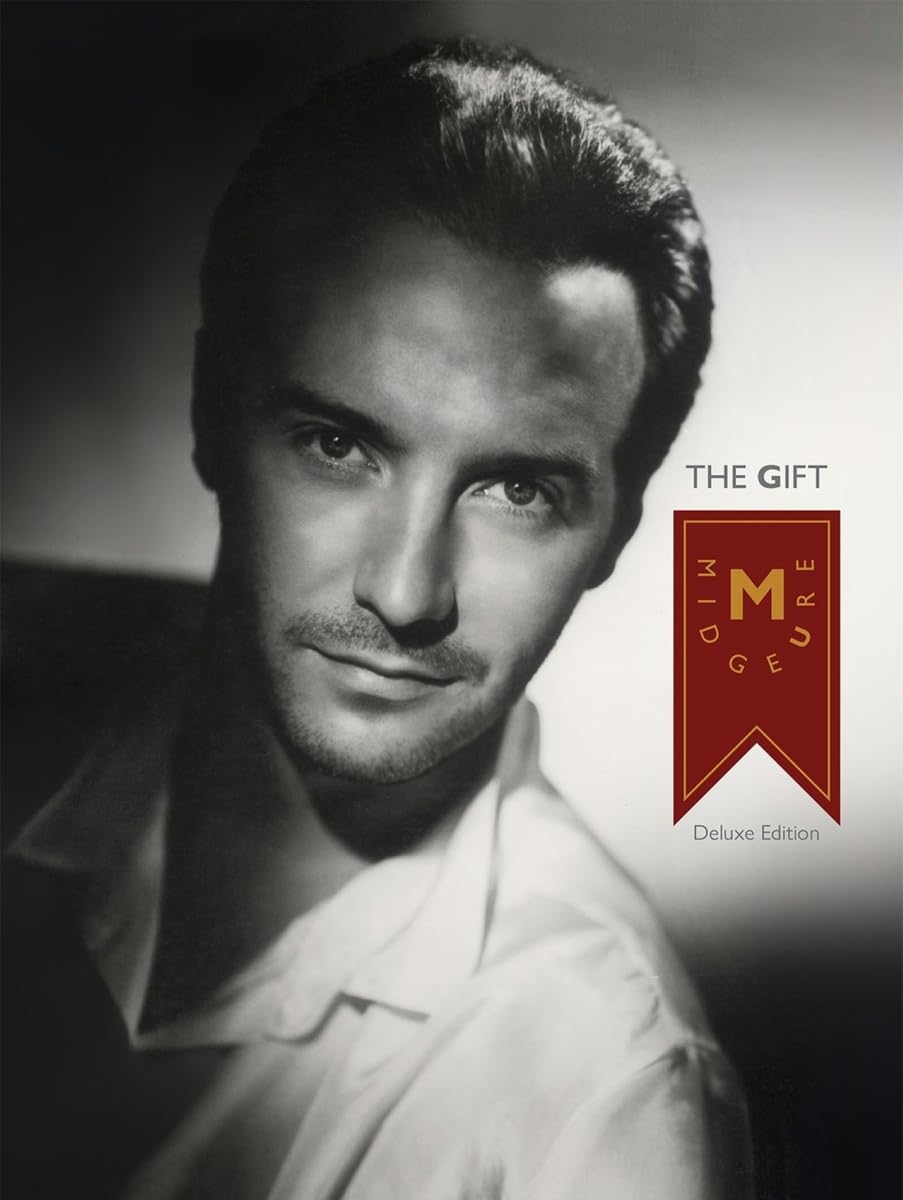

So it was when I got a call from a PR company in March 2013 about interviewing Colin Vearncombe, the voice of Black. He was promoting a two-CD deluxe edition of his 1987 Wonderful Life album. I knew the title track (which Vearncombe wrote as an ironic comment on his situation, after being dropped from his first major record deal with WEA), really liked the first single off the album, Everything’s Coming Up Roses, and had already written a short preview of the reissue for this site. While Vearncombe had never replicated the commercial success of Wonderful Life, he’d remained extremely productive in the years since, releasing a dozen more albums either as Black or under his own name. It seemed like he might have an interesting story to tell, and, fortunately, we were able to set up a phone interview at a mutually convenient time when he was available and I wasn’t at work.

The story, as told by Vearncombe, proved to be more than interesting. But somehow, despite finding the time to have a great conversation with the man, I never got around to transcribing, editing and publishing the interview. It ended up in a ‘to do’ pile and was, unfortunately, forgotten about.

It was only when the terrible news came through a couple of weeks ago that Vearncombe was in a critical condition in hospital following a car accident near Cork Airport, that I was reminded of this ‘lost’ interview and searched for and, thankfully, found the audio among my files.

Listening to the recording again, I was struck by what a friendly, thoughtful and highly articulate interviewee Vearncombe was, flitting between self-deprecation in discussing his brush with pop stardom in the Eighties to hilariously irreverent swipes at everyone from Michael Jackson to Elvis to, er, Sam Fox. He talked then about “enjoying life more now than I have ever enjoyed it” which makes his premature passing seem even more cruel. But in the words from Vearncombe’s most famous song (which were borrowed to conclude the statement on his website that announced his passing): No need to laugh or cry, It’s a wonderful, wonderful life. And, clearly, Vearncombe’s was a life well lived…

This previously unpublished interview was conducted on 11 April 2013…

SuperDeluxeEdition: You were on a few independent labels early in your career. Were you quite happy working with independents like Ugly Man [with whom Vearncombe first released Wonderful Life in 1985; it was re-released by A&M in 1987], or desperate to get another major deal after WEA?

Colin Vearncombe: I wish I could say I had a shape or a plan in my head, but I was just focused on succeeding, and that, for me, meant making a living at music. Then of course if you reach that point, you’re looking for the next point, which is a probably a bit higher, bigger, wider, longer etc.

In 1981 I was 19, I’d just left home. God knows how, but we managed to get a single [Human Features] together – that’s going to reappear in a month or two, actually – Cherry Red are putting together a four-CD compilation of roots of indie music. Bizarrely, they’ve asked about that track which made almost no impact at the time.

Pretty much the whole of my working life has been a succession of one thing led to another, and they always appeared small at the time. There have been no “wow” moments.

SDE: But you toured with the Thompson Twins…

CV: Oh, yeah, well your sins have to be atoned for, don’t they?! In 1982 I was scooped up on that. Me and Dix [Dave “Dix” Dickie, who Vearncombe started to collaborate with that year] got the gig basically because we were just of us with a tape recorder – it was easy for the crew to deal with.

Great experience, I have to say – Tom is a perennially nice bloke and knew exactly what he was doing – but it was a bank job.

SDE: Presumably, for a few years you saw your contemporaries having chart success in the Eighties’ pop scene. Did you have a desire like most teenagers to go on Top of the Pops?

CV: Yes, because that’s what there was. I also watched Whistle Test… I just read Andy Kershaw’s account of the time [No Off Switch]. Brilliant book by the way – if you haven’t read it, I’d really encourage anyone to. I mean, I laughed more than I’ve laughed in the last ten years, and also cried four times as well. The man is seriously passionate towards music and being alive generally.

Anyway, back to the point. I get a bit bewildered by this fixation on all things Eighties. One, because for me it was yesterday. My development was sort of arrested at the age of 28. The fact is that I’m actually 50 years old, but in my mind I’m 28. [The age of] 28 is when I thought I was a man. At 33, I realised that I hadn’t been then, and aged 33 is when the important things became solid and clear to me.

Two, making music as a young man in my twenties, I had no interest in Eighties pop music whatsoever. I was into Magazine and The Associates, who managed to creep into the charts as it happens. They were the acts I used to watch Top of the Pops for, hoping they would be on. I was so naive, thinking, ‘I’m glad it’s such and such presenting it; he usually has reasonable acts’. I actually talked myself into believing that they had any say on who was on, because they were the face of it. Bizarre.

But Eighties pop? Spandau Ballet, Duran Duran… I mean that’s fucking ridiculous. And unfortunately it was the beginning of the business believing that there was a formula, and if they could only find the formula. It meant of lot of looking through Music Week to see who’s got the hits this week, and then, “Okay we’ll put them with that producer”.

I went through that once or twice. Get signed and then a year later, if you’re lucky, your first record might come out while you go through this torturous process. Bollocks, complete bollocks.

SDE: So, the Wonderful Life album – did it turn out how you wanted?

CV: Oh absolutely. We are completely responsible for that, warts and all.

SDE: The record company weren’t forcing producers on you then…?

CV: No, we were very, very lucky. You see I’d already been through the mill with Warners and stuff, and then I’d been homeless. There wasn’t much you could scare me with. I was actually homeless when I wrote Sweetest Smile and Wonderful Life, but I was couch-surfing, and nothing touches you when you’re that age. For a while you can get away with it.

We noticed very quickly that the interest that was being generated with what I was doing was centred on Wonderful Life. I was living at my manager and his girlfriend’s at the time, and he said, “Look, we’re not doing a singles deal again, are we?”, and I said, “No, fuck that – they give you one shot and then you’re out the backdoor”.

We wanted an album deal; actually, we wanted two albums. So he said “Well, we better put our money where our mouth is”, and he had some money that was basically his tax, and we sat down and wrote a schedule for it. I got together with my former partner in Black, Dave Dix, and we went into a studio and we cut it. We put it out and slowly it started gathering attention.

Bless them, RCA came in with a two-album deal which meant that A&M matched it. A&M were the company I wanted because they had Chris Briggs, the only guy I’ve ever met in the business with a pair of ears and a genuine passion for music. His philosophy is sign it, encourage it, otherwise you leave it the fuck alone, and he left us the fuck alone for five months in a cheap studio.

We made the first five tracks, they heard them and went, “We’re happy, we know we’ve got our singles. What else do you want to record”, and we did another five. It was blissful. We were creating our own world to live in, and that’s the thing about [debut] albums. It’s so hard to get to, especially if that album is then a success.

SDE: Yeah exactly. You’ve got all the pressure for the second one.

CV: Oh, it’s fucked.

Given that Wonderful Life was earmarked as potentially a big hit, what was the thinking behind releasing Everything’s Coming Up Roses – which flopped – as the first single?

CV: [Laughs uproariously] Well, afterwards everyone, except Briggs, said, “Of course we always knew that Wonderful Life was a big hit”, blah, blah, blah. Hold on, Chris told me that you go with your best shot first, because you never know if you’re going to get a second shot. He really thought that Roses was going to do it, so that’s why he put that out.

And then they really didn’t know what to do, and he said “I can tell that they didn’t know what they wanted to do, because the video budget dropped from 50 grand to eight grand for the second single. It’s always in the little details that you notice these things, but Chris Briggs noticed that when he played Sweetest Smile to people, their eyes glazed over and they went somewhere, and he thought, ‘That’s interesting’.

So they put it to radio [as the second single from the album] and it just took off like a rocket and just battered down doors, through which Wonderful Life sauntered a bit later on and stayed in the Euro Hot 100 for a year. It was just extraordinary.

I went round the world twice, nearly became an alcoholic, discovered smoking dope, arrested the alcoholism, got into a bit of trouble…

SDE: When success came, were you ready for it and did it meet your expectations?

CV: Well, success is great, but fame is appalling. I mean people just go weird on you and you end up going weird as a result. They either want to kiss you or kick you, neither of which are justified in your mind. In my mind I was a kid about to be found out. They’re going to find out I’m not actually that good.

That was what was running through my mind. I still feel like I was in the apprenticeship, but I was being asked to be Babe Ruth. It was weird. Very, very strange, not pleasant at all, and actually the period of my life that I can’t remember; those 18 months, two years, when things were really flying.

With the benefit of retrospect I’d say I’m slightly envious of someone like Jarvis Cocker who was a fully formed adult man when success arrived, and remained completely sane as a result, the Jackson incident notwithstanding – I think that needed to happen anyway. Marvellous.

SDE: You must have been jetting around, bumping into the likes of Rick Astley and all those other pop stars at the time…

CV: I’m afraid that was the biggest problem for me, because there was an endless parade of TV and interviews, and you’re basically either talking about yourself or sitting around in a TV studio waiting to pretend to do something, because none of them really wanted to do live vocal. They wanted to get the picture right, and actually some of the ones that let you do live vocal didn’t have the brains to carry it off, so you could end up looking like a tool. And unfortunately, you know, Rick’s a really nice fella, genuinely nice…

SDE: I only pulled him out as an example, but you know what I mean, that kind of fluffy…

CV: Yeah, it was Sam Fox, it was Sinitta – nice people, but they’re the grist of the showbiz mill and they haven’t got really very much to say about what they do. Now you try shutting me up about this. I live in a world of ideas. I would wither and die without stimulating conversation, and that conversation for me exists whether it’s in visual arts or whether it’s in poetry, whether it’s in music.

I got used to interviews [though] and I realised that there’s only one rule: don’t be boring. They don’t really care if what you’re telling them is the truth. The first ten questions were always the same, so if you’re bored, just don’t be bored, because if you’re bored, you’ll be boring and it defeats the purpose of doing the interview. Better to stomp out and be the prima donna, because actually, even though they get pissed off, they prefer that in a way. They almost expect it. And there are more funny stories about Van Morrison – who, let’s face it, is autistic – as a result of it than any other person in the business. Would we be without him? It would be quite a hole without his stories, and they’re legion.

SDE: Back to the Wonderful Life album: it was originally ten tracks on vinyl when it came out in the Eighties, but for the CD they bolstered it with some of the B-sides and bits and bobs at the end, so that became a 15-track album. And now you’ve got this two-CD version. Do you consider the album just the original ten-track vinyl version?

CV: Well, I must admit that it was Dix and I that pushed for the extra tracks on the CD, because it was the beginning of CD, and, incidentally, the industry used the artist’s copyright to flog hardware, for instance the first 15,000 CD copies were royalty-free for more artists in that period. The only band who said you can go fuck yourself, ironically enough, was the one that became synonymous with CD – Dire Straits, and they said, you pay or you can piss off and we’ll just release on the standard format, and, of course they got what they wanted. We didn’t have that power.

We just felt CDs were being charged at a higher rate so we were interested in giving better value. Of course now I would say the fact that you can get 60 minutes on a CD is not a good reason to put 60 minutes on, and in fact I mourn the passing of the natural break.

With vinyl, one side would usually become a favourite and then you’d flip it over and you have a different relationship with the other side. You can’t do it on a CD, but Water on Snow [Black’s 2000 album] was deliberately eight songs and 35 minutes. I could do it and I made it. If I can do it, you can, or you will just reject it entirely, either of which is valid and completely fine with me.

SDE: I think you’re right. Personally, I like short albums and there’s loads of brilliant, classic albums that are eight or nine tracks…

CV: It’s the psychology of it, isn’t it? The Beatles, they had 14-, 16-track albums. Thirty minutes long; all two-minute songs. And I’ve started addressing that now in the writing, because I’ve realised that, frankly, you waffle on when you’re a young man. You’ve made your point, get out. Some songs just aren’t meant to be more than two to three minutes, and some of them, like Water on Snow – which I do realise now is eight minutes, because it’s got these different sections and it’s about something else. You put your balls on the block and invite people to stroke them rather than kick ’em. Mostly they want to stroke them – they go, “Whoa, what the hell made someone do that?”

SDE: How involved did you get with Universal on the reissue? Did they just say, “We’re going to do this, do you want to be involved or not”?

CV: They told me that they wanted to do it. They didn’t need my permission, they could have just gone ahead. I guess if they’re doing it, then it’s for commercial reasons. I mean, it’s Universal – A&M don’t exist anymore – so there cannot be any sentimental reasons.

When they said it would be two discs, I was, like what’s on the other disc? They told me they were mostly alternate versions – Wonderful Life, the original Ugly Man version, blah, blah, blah… Now, the original Ugly Man version is the one that was released later. We went back to it, did some more work and then took it to another studio. It was mixed three or four times before we got something we felt was okay.

SDE: I was giving them a close listen and they are very similar. So it’s basically the same recording, just mixed slightly differently?

CV: Yeah, well, the original was recorded on a 16-track but on two-inch tape. The original vocal didn’t change when we took it to a 24-track studio and the other eight tracks appear. If you record in the holes you don’t lose too much, and we were able to do a couple more overdubs that we felt just added some colour, but you wouldn’t really notice.

Then we went to London, got transferred to digital and added some real percussion to go with the fake stuff. They were all just details, but the vocal’s the same all the way through. The steel band’s the same…

SDE: I thought you might have had to re-record it for legal reasons, now you’re with a new record company…

CV: No. We sorted out the indie voice. We bought all of the existing stock that was left. It was interesting, I dare say they were pissed off, I mean everyone always gets pissed off with you, it doesn’t matter what you do. Trying to be equitable is a tricky business.

SDE: Where did the remix for Everything’s Coming Up Roses come from? Was that actually released at the time?

CV: Well, yes and no. America were interested in running with Roses, but they wanted a more America radio-friendly mix, so me and Dix are looking at each other going, “Hmm”. So we went back in, at the end of the session, about four in the morning, Dix said “Fuck it”, and he just started playing, and he did it in an hour and a half. I think it went on as an extra track on a 12-inch that was released in Spain only, but I had a cassette of it, and I find it really funny when I listen to it.

We used to put just as much effort and money into what they call ‘the graveyard’ – the B sides and the extra tracks for 12-inch records. I’d make an album for every album. Because no one was hanging over you, they [those tracks] were often much more the true spirit of Black.

SDE: More freedom just to do whatever you wanted.

CV: Yeah, frankly, but bonkers sometimes, in the use of sequencers alongside real instruments and nearly always a drum machine. Or we’d bring in The Creamy Whirls [singers Tina Labrinski and Sara Lamarra], basically, just because we fancied them, but they were always a blast. If the energy was flagging they’d come in – “Alright, lads” – and, woof, the energy’s up in the room again. Just great times that I remember very fondly and I like to think that asking them to go and find that stuff means that it’s probably worth a look, even if you’ve got the album from back then.

SDE: And why did Sometimes For The Asking get re-recorded, because there’s a new version of that, isn’t there?

CV: I think at the time A&M were considering a fifth single, and Dix had an idea for a [time signature] change. I seem to recall that the, seven-inch version – the tight, structured version – was pretty good, but the track on the album is obviously a 12-inch type mix. Dix loved to do that kind of thing and, to me, it just rather exposes the arse inside the pants.

The album version is big in a kind of Simple Minds way. I spent five minutes in the thrall of Waterfront, so the dum de-dum de-dum de-dum, was kind of how I started, and then I had the chord and it went somewhere else. It is quite interesting if I recall; I haven’t heard it for a while.

The other was a result of Dix’s Eighties fixation. Fortunately he wasn’t slavish, so we didn’t get too sort of shoulder pads and pushed up sleeves. But we were astonishingly lacking in self-awareness. I’ve met loads of great musicians that can’t write, because they can always tell someone else did it better, and we just didn’t give a flying one.

SDE: And the artwork for the album was quite distinctive…

CV: I got lucky there. John [Warricker], who was the recently appointed director of the A&M art department, was the UK’s first graduate of semiotics – visual language, basically – so he was not interested at all in conventional artwork for a record. In fact it was a bit of a laugh for him to even be in a record company – I think it was sort of an intellectual experiment.

We’d talk and he got to know me and he could see it wasn’t just pop. So he got in touch with Perry Odgen, the photographer who went on to make Pavee Lackeen, the [2005] film about Irish Travellers – I don’t know if you’ve seen it; it’s astonishing work.

Perry’s a really interesting guy. Former Eton. Did he attend Sandhurst? He’s almost military, nothing fazes him, but weirdly for a posh bloke he could actually stand and talk to any street kid in the world, because he’s just fearless. His photographs made it look like I was beamed down from another planet, which is the way I felt at the time, on the Dock Road in Liverpool.

And then John wanted to reintroduce the idea of putting the song titles on the front cover. The artwork is in the V&A I think, as an example of benchmark design shifts of the time. Very distinctive, which is all you really ask for.

SDE: Yeah it’s very good.

CV: I’ve never been comfortable with my own photographs…

SDE: You’re not smiling, are you…

CV: Well, I honestly never knew what people were trying to say when they smile in a photograph. If it’s like a fly on the wall, that’s one thing, but to stand and pose and be asked to smile just makes me want to bite someone’s head off. Perry never did.

It’s the most boring thing in the world being photographed and feels a lot like your soul is being taken. I understand where the Indians are coming from with that one.

SDE: Which bit of your career has been the most fun? The journey to the top, the most succesful period commercially, or the time since?

CV: I’m afraid I have a bit of a wishy-washy answer. Certainly the most exciting period was early on, before commercial success. I am enjoying my life more now than I’ve ever enjoyed it. Maybe that’s not quite the same thing. The journey is everything. It think Nietzsche said that. The struggle is everything. There is never a point of arrival. It’s a series of anti-climaxes.

Signing your first record deal, I felt let down. You know; is that all there is?

Top of the Pops, it was a disgusting experience. Meeting Jimmy Saville gave me the creeps. What’s the cameraman doing with his camera stuck up some young girl’s skirt at the back of the set? Why are they herding them like sheep? The whole thing was shit; top to bottom shit.

The biggest gig I was ever supposed to do was 90,000 people in Valencia, and a hurricane descended on the city, so it had to be moved indoors to a club; anti-climax. The anti-climaxes were just endless, and actually the biggest thrills have been small moments in the studio. You’re sat alone and the idea comes to your fore. You make the most of them.

SDE: What’s next for you? Have you got any plans to perform this album in its entirety?

CV: You know what, I haven’t been asked. I’ve been asked what would I think if I was asked. I think I’m going to have to wait and see if I was asked, because if I was asked…

I mean, I’m constantly asked why I don’t perform Everything’s Coming Up Roses? Because it’s not a very good song. I mean I stand by the recording. The recording is what gave me the lift; I can still get a lift listening to it. I can’t remember what the bloody song was about. If I can’t remember, how is anyone else supposed to know?

As a self-professed lover of the word, it has to have its own internal logic, even if that is nonsense, and it doesn’t even work for me at the level of nonsense to be honest.

If someone came up with the money and I was able to actually put together a killer band to play the album live… but that’s only 40 minutes or so. What about the rest of the gig?

These days I have to strategise [sic] and forget about succeeding in any other terms other than, do I actually think it’s good, and fortunately I have a couple of people around me who think in exactly the same way.

Callum McColl who’s playing with me on this tour is like a brother, in the sense that we bicker with passion, and I think he’s an astonishing musician, and he’s an engine for me, because I am a very up and down person. I’m a Gemini, you’ve got to be careful which one you’re talking to. I can get really down and he’s the guy that kicks me. He gets me up again, often, and I am lucky I have a few of those people around me.

So I guess that was no answer, wasn’t it? [Laughs].

SDE: I’ll make sure that answer’s in the blog, if someone comes up with the money and you never know what might happen.

CV: I can’t believe that that many people are interested. A few years ago I was in Leeds, and there’s a promoter called John Keenan who’s been around since the very beginning of the business, one of the good guys. John said to me, “Sad truth is, Colin, I could get more people for the Black tribute than I can for you”.

And if that were true, then I guess it might even be a valid idea [to perform the album live], because they’re buying into it from a nostalgic point of view.

It’s been an ongoing problem for me since the very beginning. If people remember me at all, it’s a 25-years-out-of-date memory. I live now, not then. I mean if you like it, why don’t you just sit and listen to the record?

But people want to go out and see Pink Floyd and they can’t see Floyd or Zeppelin or AC/DC, and the [tribute] acts tend to be the better acts. I know it sounds terrible name-dropping, but Dave Gilmour told me that he had the Australian Pink Floyd play at his 60th birthday and he said: “Do you know what, they were better than we ever were.”

SDE: They must have loved doing that gig.

CV: Oh they would have been bricking it. Bricking it. But it’s a very different thing to recreate. When you’re the band, the act that’s generating the thing, it’s a blank canvas. The job’s already done … At which point you’re going to have to shut me up.

SDE No, no… well, listen thanks very much for the time and good luck with your touring and good luck with this reissue. I think it’s out already isn’t it?

CV: It must be, because people have started turning up with copies for signing at the shows. I’m generally surprised because Wonderful Life is probably more famous than I’ll ever be again. I’m aware that less than half of the people that love that song could tell you who it’s by, who wrote it. The song itself, it just transcends all genres, age and everything, but the album? Hmm…

SDE: It has got two top 10 hits on it, and also the amount of copies that shifted in those days is pretty substantial compared to today

CV: True enough. I mean, to be told at one point that it was outselling Michael Jackson three to one in parts of the UK was just jaw-dropping. The difference is now I can’t actually sit still for almost a single song Michael Jackson recorded. It just sounds like cobbled bollocks. Even with the obvious flaws, I can still live with what I did.

SDE: You’re gigging at the moment aren’t you?

CV: Yeah, and I’ve been doing some recording and writing this week. We actually wrote a theme tune for a Bond film that hasn’t been made. It’s fucking brilliant. Now we’re talking orchestras and how we can possibly afford them. It’s a cracking song. I can’t wait, because I occasionally perform Bond tunes.

SDE: Do you?

CV: Yeah, John Barry and, after him, [Ennio] Morricone are the reasons why I do what I do. I know way back I talked about Elvis [being a key influence], and I did see an Elvis film and it was cool, but you know, forever in my mind he’s a fat fool in a little cape doing stupid, crap things in Las Vegas. Barry and Morricone still give me the chills. It’s my childhood and it resonates in a way that nothing else does for me. Actually when you know that, you know where all the melodramatic flourishes and pretentious over-reaching come from in my stuff. It’s them; they’re to blame.

Rest in Peace Colin Vearncombe 1962-2016

Interview

Interview

By Paul Sinclair

31