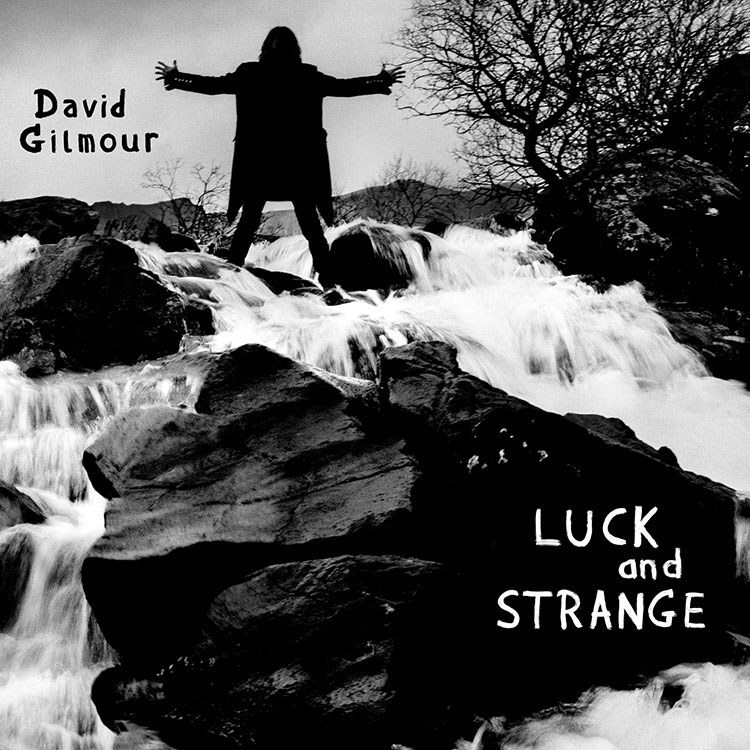

David Gilmour / Luck and Strange review

By David Quantick

If the “solo project” is an important part of rock’s rich tapestry, it’s often more because of what it signifies rather than the actual music it produces. Solo projects exist for many reasons: sometimes motivated by vanity (sometimes by insanity), sometimes the urge to do something different to your main band, sometimes the desire to get your own songs recorded, or occasionally just as a way of filling up time between tours.

Luck And Strange is David Gilmour’s fifth solo album since 1978’s David Gilmour (not counting live albums and collaborations). In the years between that solo debut and Luck And Strange, Gilmour worked on two Pink Floyd albums with their old bass player and three more without, fitting in solo records when he could. Most of them avoid the stadium trademarks of his big band (although the gorgeous On An Island has the most Floydian slips), and introduce their own, distinctly Gilmourish tropes: more personal lyrics (generally written by Polly Samson, who is married to Gilmour), the odd Mark Knopfleresque acoustic song, and a comparative sparseness to the sound, more suited to filling a room than a stadium. All of them have been different (2015’s Rattle That Lock is almost funky) and all of them have been pretty good.

The combination of older music legend and younger producer has been tried by many artists over the years and often with mixed results, but on this occasion it really works.

David Quantick

This time round, Gilmour has brought in a fresh producer. His previous solo albums have largely been produced by himself, but Luck And Strange is a collaboration with Charlie Andrew, producer of Alt-J, Madness, Eugene McGuinness and many other artists who didn’t join Pink Floyd in 1967. The combination of older music legend and younger producer has been tried by many artists over the years (Johnny Cash and Rick Rubin, Paul McCartney and Nigel Godrich) and often with mixed results, but on this occasion it really works. Andrew brings an immediacy to Gilmour’s sound, a lean conciseness even on the longer songs, and even some intimacy, all of which suit these new (largely new, that is) songs. There are, inevitably, moments here that recall Pink Floyd (most notably the appearance of the late Rick Wright on an extended jam on the title track, recorded in 2007), but this is the freshest-sounding record of Gilmour’s long career – and, most significantly, the most intimate.

Part of the success of Pink Floyd was their epic quality: they didn’t, as a rule, write love songs. Over the years the lyrics became less and less personal and more concerned with telling the world off for various things. Even later Pink Floyd albums seemed like pronouncements from a giant floating head with a great light show. Gilmour’s own records were more personal, but when he did write an intimate song, many listeners assumed it was about a former bandmate.

Luck And Strange changes all that. Polly Samson’s lyrics have always made David Gilmour sound more emotional, putting that great white soul voice to better use, but on this record, she brings everything back to the human level. On ‘Dark And Velvet Nights‘, she adapts the words of a poem she wrote for Gilmour on their wedding anniversary, while ‘Sings‘ (the jewel in the coronet of this album) is a lyric that you couldn’t imagine being sung on The Wall: “Darling, turn back the clock, Gilmour sings, “Give me time, make it stop/ Let’s hold back the news/ Stay inside this cocoon.” It’s a warm insight into a real relationship: “Darling don’t make the tea, stay and snooze here with me.” It’s a beautiful song, the loveliest tune on this record and it ends with the sound of a child (presumably a Gilmour) talking : “Sing, daddy!”

This is an album full of Gilmours. Normally such things are distressing for the listener – “we’ve got my uncle on backing vocals, and the nanny plays a great saxophone solo” – but on Luck And Strange it works. Gilmour and Samson’s daughter Romany plays and sings lead on one song, while their sons Gabriel and Charlie contribute backing vocals, and lyrics. With Gilmour girls and boys alongside their parents, this is a family album, a closed and intimate circle in contrast to the open squabbles of Pink Floyd (Gilmour’s desire to not be Pink Floyd is strong: talking about his touring band, he said: “It was all too robotic, and some people would have been better off in a Pink Floyd tribute band. So I thought we’d get people who are genuinely creative and give them a little more space.”).

This is a record where two people are talking to each other; there’s an inventiveness that’s

David Quantick

new here

But is it any good? David Gilmour has claimed in interviews that it’s the best thing he’s done since The Dark Side Of The Moon, which is a powerful assertion. Still, he may be right: alongside the consistency of the album – there are, unlike with The Wall and The Final Cut, no bad songs – and the sheer emotional power – this is a record where two people are talking to each other; there’s an inventiveness that’s new here. There are, as mentioned, nods to the past: age cannot wither nor custom stale the infinite brilliance of Gilmour’s guitar playing, which is evidenced everywhere from the brief instrumental introduction ‘Black Cat‘ to the gorgeousness of ‘A Single Spark‘. ‘Dark And Velvet Nights‘ has an epic introduction which would have sounded great on Meddle, and there’s a (very deliberate) use of the sonar keyboard sound from Echoes on ‘Scattered’ (a song which also nods to Rick Wright in the lines “A man stands in a river/ Pushes against the stream”). But mostly Luck And Strange is, while still being very David Gilmour, a new David Gilmour.

Perhaps the best example is ‘The Piper’s Call‘. A song previously released as a ‘single’, this piper is very much not at the gates of dawn: it starts with a sunset feel, reminiscent of something from On An Island, features lyrics about “dreaming spires” and “six string masters of an expanding universe” but then races away from Grantchester Meadows with a chugging, nagging guitar that’s possibly the most muscular thing David Gilmour has ever recorded.

Similar but different is ‘Between Two Points‘, which wasn’t written by Gilmour and Samson but the indiepop band The Montgolfier Brothers. Sung by Romany Gilmour in a clear but distant voice, it’s a terrifying song, a plain but beautiful melody with a bleak lyric about someone who “stopped hoping at an early age”. “They’re right,” sings Gilmour, almost blankly, “You’re wrong.” It’s a powerful, dark song that stands out in the fuzzy positivity of the rest of the album.

On CD and blu-ray editions Luck And Strange is appended with ‘Yes, I Have Ghosts’. First released in 2020, it’s a ballad in the Leonard Cohen tradition, all romantic guitar and fiddle. You can see David Gilmour coming up to you in a taverna singing this one. The ghosts referred to are romantic ones, but the title makes sense in other ways: David Gilmour, and his career, are filled with ghosts. This album, however, is a fantastic exorcism of that past.

And it’s definitely the best record he’s made since The Dark Side Of The Moon.

Review by David Quantick. Luck and Strange is out now.

Compare prices and pre-order

Gilmour, David

Luck and Strange - black vinyl LP

Compare prices and pre-order

David Gilmour

Luck and Strange - Amazon exclusive CD with alternative cover

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Compare prices and pre-order

David Gilmour

Luck and Strange - Amazon exclusive opaque vinyl with alternative cover

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tracklisting

Luck and Strange David Gilmour /

-

-

All 13 tracks in Dolby Atmos Mix and (96/24) Hi-Res Stereo

- Black Cat (Gilmour)

- Luck and Strange (Gilmour/Samson)

- The Piper’s Call (Gilmour/Samson)

- A Single Spark (Gilmour/Samson)

- Vita Brevis (Gilmour)

- Between Two Points (Tranmer/Quigley)

- Dark and Velvet Nights (Gilmour/Samson)

- Sings (Gilmour/Samson)

- Scattered (D. Gilmour/Samson/C. Gilmour)

Bonus tracks

- Yes, I Have Ghosts (Gilmour/Samson)

- Luck and Strange (Original Barn Jam) (Gilmour/Samson)

- A Single Spark (Orchestral) (Gilmour/ Samson)

- Scattered (Orchestral) (D. Gilmour/Samson/C. Gilmour)

-

Reviews

Reviews

By david quantick

46