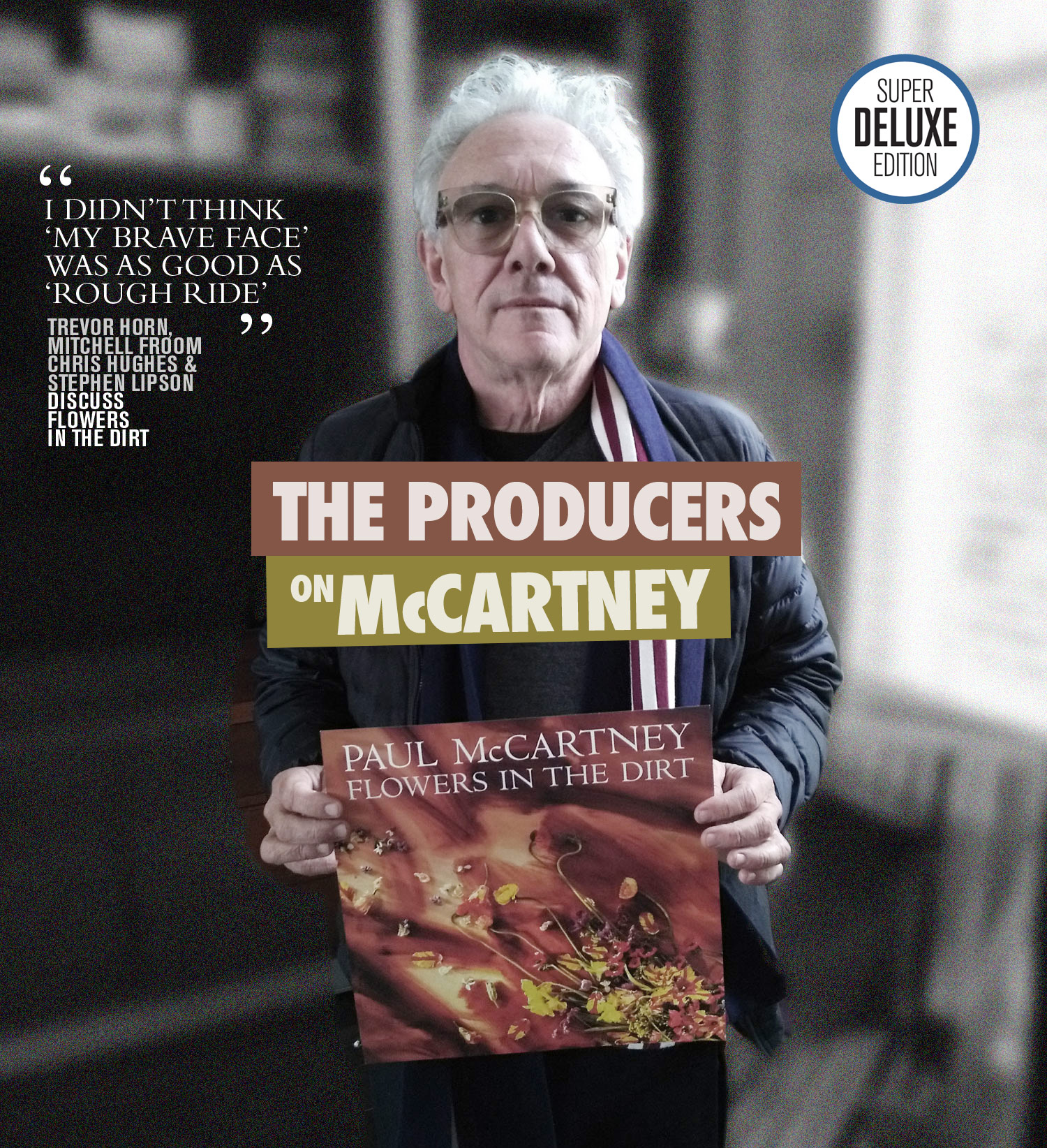

In Their Own Words: The Producers discuss McCartney’s Flowers in the Dirt

SDE talks to four producers who worked on Paul McCartney’s Flowers in the Dirt.

TREVOR HORN was best known for his work with Frankie Goes To Hollywood and was one of the hottest producers on the planet in 1987, when he and his partner STEPHEN LIPSON drove down to Paul’s studio to work with the ex-Beatle. MITCHELL FROOM was a new producer at the time, who was basking in the success of delivering a US #2 hit for Crowded House (Don’t Dream It’s Over) and CHRIS HUGHES was an experienced and highly respected talent who’d produced (and played drums) on all the Adam and The Ants albums before playing a key role in Tears For Fears‘ mega-selling Songs From The Big Chair (he also co-wrote Everybody Wants To Rule The World).

It’s a fascinating read as all four men thoughtfully recall the pleasures and challenges of working with a musical legend at a period when Paul needed to come back with a strong album for his impending 1989-1990 world tour.

All interviews conducted by Paul Sinclair in late 2016/early 2017. Also edited by Paul S.

Trevor Horn: I had met him in 1983 because I was working in Air Studios with Yes and Spandau Ballet, I think, and I always remember the first time I ever met him I was on the Space Invaders machine and I was doing pretty well and suddenly a voice behind me said, “Trevor, if you want to do this I’ll show you how to turn the machine” and of course it was him and I was pretty knocked out because I’d been a huge Beatles fan from 1963 [onwards]. I’m absolutely that generation, you know, I grew up on it, The Beatles and The Stones and then Bob Dylan and he was very charming. He knew my name, that’s a pretty amazing thing if somebody knows your name. So, I knew about him and I’d followed his solo career up to a point.

Trevor Horn: I had met him in 1983 because I was working in Air Studios with Yes and Spandau Ballet, I think, and I always remember the first time I ever met him I was on the Space Invaders machine and I was doing pretty well and suddenly a voice behind me said, “Trevor, if you want to do this I’ll show you how to turn the machine” and of course it was him and I was pretty knocked out because I’d been a huge Beatles fan from 1963 [onwards]. I’m absolutely that generation, you know, I grew up on it, The Beatles and The Stones and then Bob Dylan and he was very charming. He knew my name, that’s a pretty amazing thing if somebody knows your name. So, I knew about him and I’d followed his solo career up to a point.

Stephen Lipson: I had worked with him before, a few years earlier, with Ringo. At a studio where I was the house engineer, in the South of France. And that was a really weird experience, in many ways. It was a Ringo album called You Can’t Fight Lightning. That was the most bizarre experience for me. I was much younger and I hadn’t had any success and there I was… assisting. I was going to engineer and they panicked at the last moment and got Peter Henderson in. And funnily enough I was over the moon that they had done that because it took the pressure off, but I could observe and see how he did things. It was good; really interesting.

Stephen Lipson: I had worked with him before, a few years earlier, with Ringo. At a studio where I was the house engineer, in the South of France. And that was a really weird experience, in many ways. It was a Ringo album called You Can’t Fight Lightning. That was the most bizarre experience for me. I was much younger and I hadn’t had any success and there I was… assisting. I was going to engineer and they panicked at the last moment and got Peter Henderson in. And funnily enough I was over the moon that they had done that because it took the pressure off, but I could observe and see how he did things. It was good; really interesting.

Chris Hughes: I was working at a studio in Oxford circus, you know AIR, before it moved up the hill. It was four studios, and I think Townshend was in one, McCartney was in one, and I was working with Adam and the Ants at the time. And Paul used to pop his head around the door and nose about and see what everyone was doing. It was quite a community of people. I got chatting to him and he was working on either Pipes of Peace or Tug of War, one of those, I can’t remember. He was with George Martin, and I think they were in Studio 4, and I got chatting to him and he seemed very friendly, and I got to meet Linda and chat to her in the canteen.

Chris Hughes: I was working at a studio in Oxford circus, you know AIR, before it moved up the hill. It was four studios, and I think Townshend was in one, McCartney was in one, and I was working with Adam and the Ants at the time. And Paul used to pop his head around the door and nose about and see what everyone was doing. It was quite a community of people. I got chatting to him and he was working on either Pipes of Peace or Tug of War, one of those, I can’t remember. He was with George Martin, and I think they were in Studio 4, and I got chatting to him and he seemed very friendly, and I got to meet Linda and chat to her in the canteen.

Mitchell Froom: I got asked originally to work on the songs that he wrote with Elvis Costello. And I think it came about because Paul’s manager’s wife at the time was a big fan of a Crowded House record that had just come out. So, I don’t know exactly what happened, but he may have played some of it to Paul, and Paul is just open minded, and is always interested in working with different people. Paul was on Capitol in the US, and I was a new producer and just had that success [Crowded House – who were on the same label], so the people at Capitol were also interested in me doing it. So there may have been some politics, I have no idea.

Mitchell Froom: I got asked originally to work on the songs that he wrote with Elvis Costello. And I think it came about because Paul’s manager’s wife at the time was a big fan of a Crowded House record that had just come out. So, I don’t know exactly what happened, but he may have played some of it to Paul, and Paul is just open minded, and is always interested in working with different people. Paul was on Capitol in the US, and I was a new producer and just had that success [Crowded House – who were on the same label], so the people at Capitol were also interested in me doing it. So there may have been some politics, I have no idea.

Trevor Horn: He was being managed by a guy called Richard Ogden, I think, at the time when I came to work with him. It was Richard Ogden who said, “Do you fancy doing a few tracks with Paul?” And I wasn’t sure to be honest, but I said, “Yes, I wouldn’t mind working with him” and he said, “Well you know he’s doing auditions for a band?” and I said, “Oh really, if he’s doing auditions for a band I’ll come along and play the bass on one of the auditions. It’d be a good chance to sort of meet him for half an hour.” I always remember the rehearsals were in the East End somewhere in a place near the Dartford Tunnel or somewhere there. The rehearsals were meant to start at 5.30pm and I jumped in my car, but I could see pretty quickly that I was going to be late. So, I phoned ahead and said, “I’m running a bit late” and the guy said, “Mr McCartney likes everyone here for 5.30 on the dot”. I said, “Well I ain’t gonna be there, pal, so just tell him I’ll be a little bit late”. I’d sort of confused everybody a little bit; to all the crew and everyone I was a musician showing up to audition. But in my head, I was just coming over to sort of check out Paul. I wanted to go and look at him and feel how and if it would work. Because I don’t want to find myself in some funny studio with some guy I didn’t get on with. So, I did this, played it, he had a great drummer and Nicky Hopkins played the piano. I always remember that, it was like a four-piece; it was good and I liked him. I liked Linda too, I really liked Linda.

Mitchell Froom: I was just starting as a producer. I obviously came of age during the Beatle era, and those recordings are pretty much unmatched and have been unmatched since, and so I was mostly attracted to that feeling. I was a huge fan of his when I was very young, so I was a little intimidated when I first spoke to him, but I couldn’t say no to it. First of all, I liked the songs that I was going to get to work on, and so I felt like it was part of something exciting. And of course, the joy of my job is you get to be in the room with people. I will never forget Paul on that single My Brave Face, Paul picked up the Hofner bass, and I was right next to him, and he started playing it, I will never forget it. Through the mixing and whatever at the time, it got somewhat diluted, but boy at his best he is incredible.

Chris Hughes: When he was trying to get Flowers in the Dirt finished, and he’d been working with Elvis and various other people, there was a track, Motor of Love, a track that he’d half started and liked but didn’t have much time, wasn’t sure it was any good, etc., and his manager at the time was a good mate of my manager. They obviously had a discussion, and Paul said, “oh yes, I’ve met him, yes, he’s a nice guy, maybe we could do something…”

Chris Hughes: When he was trying to get Flowers in the Dirt finished, and he’d been working with Elvis and various other people, there was a track, Motor of Love, a track that he’d half started and liked but didn’t have much time, wasn’t sure it was any good, etc., and his manager at the time was a good mate of my manager. They obviously had a discussion, and Paul said, “oh yes, I’ve met him, yes, he’s a nice guy, maybe we could do something…”

Trevor Horn: Richard [Ogden, Paul’s manager] was talking to me about writing with him. I didn’t fancy that really… for my own reasons, you know, I thought… I just didn’t know. I didn’t know what it would be like. So, I came up with this other idea and I said to him, “Look, why don’t I come down for two days with this guy I work with, Steve Lipson, and we’ll see what we do in two days, you play me whatever songs you’ve got, I’ll pick a song and we’ll try and do it in the two days”. I remember he said, “I don’t know if I like that idea”.

Stephen Lipson: I can’t remember what we were coming off the back of. Whatever it was, it was probably quite close to Slave to the Rhythm, which was a year to do a song. So, as we were in the car, I remember it quite clearly, Trevor said “let’s just spend no more than two days on any one song.”

Trevor Horn: I remember reading an interview [with Paul] where he said it was his idea. It wasn’t his idea. I’m not going to argue about it. You know, I like him, but it’s like all musicians, everybody remembers things slightly differently. I was a bit surprised when I read that, but then I understood why he said it, because it sounded like a good thing [to say] in an interview…

Mitchell Froom: He told me, “I know Trevor Horn he is known for working for three months on one song, so I told him we have one day”. So it’s sort of like he thought it through and thought what would be a cool way to maybe try to work with this guy…

Stephen Lipson: Paul wouldn’t have suggested that. Let’s be honest, if you are employing Trevor Horn you don’t do it and chop his wings off. So logically it would have come the other way.

Chris Hughes: I talked to Paul at length about the process of making the record and who had done what and for what reason, and the parts of it he liked. My impression was that he was happy to work with other people and be guided and have it be more of a collaboration than he’d done for a while. But it’s still very much what he wants to do, at the end of the day. And he has the tendency to reinvent how things are, in order for them to make sense to him.

Chris Hughes: I talked to Paul at length about the process of making the record and who had done what and for what reason, and the parts of it he liked. My impression was that he was happy to work with other people and be guided and have it be more of a collaboration than he’d done for a while. But it’s still very much what he wants to do, at the end of the day. And he has the tendency to reinvent how things are, in order for them to make sense to him.

Trevor Horn: I was initially not very keen because, you know, if you’re a record producer one of the secrets of having hits is to work with people who have hits, if I’m honest about it.

Stephen Lipson: This is what I find quite interesting, a producer can only work with the materials they have got. There is only so much they can do.

Trevor Horn: I was more worried from a point of view of going into somebody else’s world and being there for too long and it all becoming a bit too comfortable and easy or whatever. So, I wanted to try and give it a sense of urgency. Anyway, like I said, at first he said he wasn’t very keen on the idea and then the manager phoned me back and said, “Okay, he’ll give it a go, so you come on Monday.”

Mitchell Froom: When I got there, to work on those four songs, I think pretty much everything had been recorded, if I’m not mistaken. I know that the thing he did with Trevor Horn was done. I got sent the original Elvis demos, the acoustic ones, just them in a room together, and there was some great stuff in there, great songs. At one point, I listened back to those acoustic demos and I thought Paul should just play some drums on this and just put this out, because they’re great.

Trevor Horn: With the likes of Frankie Goes To Hollywood, I was in control of it – for better or for worse. But with Paul, it’s Paul’s record, you’re making his record.

Stephen Lipson: I know everything that I did with Trevor, which wasn’t that much, the two of us – the Pet Shop Boys, Simple Minds and Paul McCartney – but the artists weren’t there a great deal. McCartney, it was obvious, was going to be there.

Trevor Horn: So, we arrive at his place [Hog Hill Mill studio], loads of crew, there’s loads of instruments at the studio, and it is a bit like a kind of museum. He’s got his old Beatle bass with his set list from Candlestick Park… It had beautiful views and I always remember the first thing I did was close all the windows – let’s imagine we’re in a studio in London. I was a record producer, I was there to make a record, so [we need to] kind of ignore that stuff. It’s too nice, if you know what I mean. I went up to an upstairs room and he played me five songs, with him and a guitar and the one I liked was this song called Rough Ride and I thought it had a certain poignancy to it, “a rough ride to heaven”.

Stephen Lipson: It’s a great setup – he has got the windmill, a big studio, and then this rehearsal barn. And so he should have! Trevor went upstairs, while I was setting up my gear because I had a whole load of new gear that I had spent months organising. It was state-of-the-art, drum boxes, computers, all pretty much ahead of the curve. So I had set it up, which took the morning, and by lunch Trevor came down and he said to me that he had found a song, and this song would be good because “you know that rhythm you have got in your drum box programme – the song would work really well with that rhythm”. That was the basis on which he picked the tune.

Trevor Horn: Steve Lipson and I lifted the beat [for Rough Ride] from Experience Unlimited which is a go-go band that we really liked.

Stephen Lipson: When we got there it was just him, so we were the band, the three of us. I had this bass sound I had been working on, it was a huge bass sound, two synths. I don’t think anyone had gone this far with all the gear. I had a little mini-keyboard and so McCartney comes in and I was fiddling around and he went oh you play the bass. So I was the rhythm section; bass and drums. Trevor had a keyboard and Macca was playing the guitar. And we started going through this tune and I remember at numerous points thinking this is weird, I’m playing the bass and that is Paul McCartney – fucking hell.

Trevor Horn: We started to put the song over that beat and he liked it, I could tell he was liking it and I always remember I changed the chords in the middle eight, I just re-jigged them and he said, “Oh no, those aren’t the chords for the middle eight” and I said, “They are now” and he laughed. Because as I said it was just the three of us so we’re going to kind of change things around.

Stephen Lipson: There was no ‘Paul Goes To Hollywood’ version of Rough Ride. I don’t remember anything like that. I think it developed and it was finished.

Trevor Horn: No, there wasn’t. There was a moment where he was playing [something else], people are playing, I think Linda’s playing the Mellotron and he’s playing electric guitar and one of the crew came running in because we were trying to finish off Rough Ride and shouted, “Quick, quick he’s playing, go into record” and Steve had a stick that we used to call the ‘lipstick’, Steve’s lipstick, and he poked this guy and he said, “And we’re mixing, out, out” and poked him and the guy went out, we didn’t go into record.

Stephen Lipson: The stick was something I had at Sarm [studios] because the consoles, the SSRs are very deep. And I get so fed up, so I got this stick and I hit the buttons with the stick because I was accurate with the stick.

Trevor Horn: The other thing I remember about Rough Ride was that he only sang it three times and it was mostly the third take. He sang it three times and he came into the control room and I said, “The third take was the take” and Lippo said, “Yes, first two weren’t up to much, but the third one was good”. That was the difference between me and Steve, I would never say something like that, I always look for the positive!

Stephen Lipson: It was a bit weird at moments. We are going through it and he has got all his guys in the room, a roadie and a driver and I think a tech, three guys. And stupidly at one point I had just hit ‘stop’ – this was in the afternoon. I said, “you know what, we have been going through this song all day and every time we get to the middle eight it is rubbish”. And all these guys are looking at me, and Macca, and Trevor, I said it without thinking. They are all like daggers looking at me, a big silence. And finally, Macca goes “oh yeah, so what do you think we should do about it?” And quick as a flash, I said “I have no idea, it is not my department, I am just telling you the middle eight is no good.” I said “that is your department. My department is to tell you.” And he looked at me and went okay I’ll go and re-write it. And he went upstairs, came down half an hour later with another middle eight. But it was a real moment, I kind of wish I hadn’t done it… And so we got the track down and then he told me to halve the speed on the tape machine – we were working at 30 inches per second – he said “go to 15, I’ll do some drums”. And he did some drums on it.

Trevor Horn: Steve Lipson was a pretty dry sort of character. He didn’t have much patience for anything or anybody. We had a great two days in the end, we really enjoyed it. I came away from that, the first two-day session feeling that it had been a real success. The other thing that I remember about Rough Ride was that we brought Linda in and Linda played some really great synths. She came up with this idea for a mini-moog part. We really liked Linda. So I was pretty keen to get her on the record. She also seemed to have a really good influence on him. He really liked her, if you know what I mean. [I know] that’s a dumb thing to say, but he did. Sometimes you meet people who don’t like their wives, you know.

Trevor Horn: Steve Lipson was a pretty dry sort of character. He didn’t have much patience for anything or anybody. We had a great two days in the end, we really enjoyed it. I came away from that, the first two-day session feeling that it had been a real success. The other thing that I remember about Rough Ride was that we brought Linda in and Linda played some really great synths. She came up with this idea for a mini-moog part. We really liked Linda. So I was pretty keen to get her on the record. She also seemed to have a really good influence on him. He really liked her, if you know what I mean. [I know] that’s a dumb thing to say, but he did. Sometimes you meet people who don’t like their wives, you know.

Stephen Lipson: She was wonderful; absolutely brilliant. I haven’t got a bad thought in my head about her. She was the best; so warm. She invited us into their lives in a really lovely way. And that was Rough Ride. And then we mixed it.

Chris Hughes: I got very close with Linda. She was great. I spent a lot of time with her, and both of them; just hanging out. The pair of them invited me around to their place and cooked supper and they were great. Linda, particularly, was wonderful.

Trevor Horn: No, we had such a good experience on Rough Ride that he wanted to do it again. There was a lot going on and it caused a little bit of friction at one point because Simple Minds suddenly wanted to be finished and I had to cancel a couple of sessions and put them back a couple of months. I was surprised at the time that Rough Ride wasn’t a single. I didn’t think My Brave Face was as good as Rough Ride.

Chris Hughes: Should have been [a single]. Yes. It’s very hard to know at what point – I remember a conversation with his manager, and he’d gotten to a point where his influence, it was getting tricky, and I think Paul was having some trouble with him. It’s quite difficult telling Paul he’s doing something wrong, which is a fucking stupid starting point anyway. You shouldn’t be saying it’s wrong. But it’s quite difficult to point out weaknesses and things could be better and all this sort of stuff on one level, because he’s been so right for half a century. The amount of times he’s been right, and on an intuitive level, it’s very difficult to be philosophical about why something’s not right.

Chris Hughes: Should have been [a single]. Yes. It’s very hard to know at what point – I remember a conversation with his manager, and he’d gotten to a point where his influence, it was getting tricky, and I think Paul was having some trouble with him. It’s quite difficult telling Paul he’s doing something wrong, which is a fucking stupid starting point anyway. You shouldn’t be saying it’s wrong. But it’s quite difficult to point out weaknesses and things could be better and all this sort of stuff on one level, because he’s been so right for half a century. The amount of times he’s been right, and on an intuitive level, it’s very difficult to be philosophical about why something’s not right.

Stephen Lipson: I don’t remember any discussions about singles. No. We were involved in an album, and because we weren’t doing the whole album, I don’t think there was much of a discussion about that.

Trevor Horn: I do think that it is better if one producer can do a whole album. It’s also one producer’s choice of songs out of what’s available. It’s probably why, whenever I listen to Flowers in the Dirt, if I put it on, I just generally listen to Rough Ride because to me that was the one that was really good.

Chris Hughes: I have to say, given my choice, I love being right amongst the narrative, yes. I come from that period of time where albums are incredibly important. They can journey well and make a statement and be brilliant for 40 minutes. I love that. That obviously wasn’t the case in Flowers in the Dirt, but I love all that.

Stephen Lipson: It’s more business-like when you are doing one-off, or a handful of tracks. When you do the whole album, you are in for the duration, long-haul. It’s a different dynamic.

Mitchell Froom: I am maybe a bit of a snob in that I’ve always just gravitated towards albums that have a single point of view, I just like them. Albums that sound like of a place and time, it sounds like certain people are in the room together, and when you hear it you just wish you were in the room with those people, because it sounds like a great thing was happening. And so, if there’s one thing that Flowers in the Dirt obviously can’t have, or it doesn’t have, it’s that.

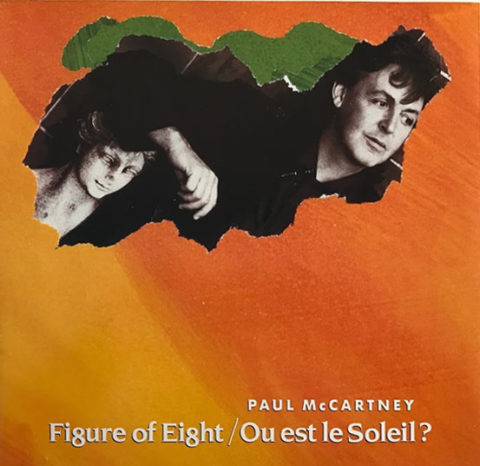

Trevor Horn: Figure of Eight initially was like a rock ‘n’ roll track… [Trevor sings in ‘Great Balls Of Fire’-stye] “do, do, do, do – you got me running in figure of eight, do, do, do, do…” and it wasn’t so easy to find a middle ground for it, but I always remember, we worked until about seven o’clock with him on the first day and then he went and we worked until about midnight and we changed all the chords, every single chord in Figure of Eight we changed and we made it more like a U2 track. Well, I thought we made it sound more modern and the next day when he came in and heard it he wasn’t very happy…

Stephen Lipson: He came in the next morning and went berserk. He just went mad, like “what have you been doing? What have you done?!” It was that sort of conversation and I remember at the time thinking that there are so many aspects to this that are interesting. Firstly, what is the problem? Yeah, we did a bit of work on it, secondly he was in a real mood. Maybe something had happened before he got to the studio, I don’t know. It was just a weird moment. It changes how you view someone.

Stephen Lipson: He came in the next morning and went berserk. He just went mad, like “what have you been doing? What have you done?!” It was that sort of conversation and I remember at the time thinking that there are so many aspects to this that are interesting. Firstly, what is the problem? Yeah, we did a bit of work on it, secondly he was in a real mood. Maybe something had happened before he got to the studio, I don’t know. It was just a weird moment. It changes how you view someone.

Trevor Horn: He said, “I always saw this as a rock ‘n’ roll kind of track, like an old-fashioned rock ‘n’ roll” and I said to him, “Well that’s great if you want to do it like that, but what I would suggest is you get on the phone and you get yourself some really good rock ‘n’ roll musicians because me and him don’t like rock and roll, you know me and Steve, we just don’t like it, we don’t do it, so there’s three of us, so you’re kind of outnumbered on this one”. He took it – that’s what I liked about him, you see, because he took it really well. He said, “Alright, I get what you mean”. Because I wasn’t kidding, I wasn’t being awkward or anything. To me it was 1988, so going “do, do, do, do..” didn’t seem like a good idea. I remember he said, “Let me understand what you’ve done”. So we spent a while and he got the chords into his head that we’d come up with and he changed a couple of them and then we finished the track. But he was never totally happy with that track, Figure of Eight.

Stephen Lipson: it didn’t get resolved because he re-recorded it with Chris Hughes.

Trevor Horn: I didn’t know what he wanted from that track and I thought that where we’d got to with it, in two days, was really good. I didn’t think if we spent another week it would be any better and I didn’t know if, in the end, the version that he came up with [with Chris Hughes] was any better than the version that we did.

Stephen Lipson: The difference was minimal, from what I could make out.

Trevor Horn: It was something he was looking for that he didn’t find and I didn’t want to go back to it. They sent it over to us at one point and said, “Do you think you could do a better mix of this?” But I listened to it and I listened to the mix that we’d done of it and I didn’t think we could. We could do a different mix, but sometimes when you’re up against it – when we mixed it, we were up against it time-wise – you come out with a better mix and you go back and you’ve got loads of time and you go up your own backside, so I didn’t want to go there. I know I’ve got a reputation as being somebody who takes ages and ages. In actual fact, I made a Bryan Ferry record in four days, I don’t think anybody else managed to ever do that before. I think it surprised even Bryan. So I could be quick if I had to be. Some things you don’t spend that kind of time on because they’re not going to be any better for it.

Stephen Lipson: I think he changed the melody. Not the melody but the balance so that the high note became the dominant note in the verse, whereas we had the lower note as the dominant note.

Trevor Horn: I wasn’t upset when our version wasn’t released as the single. I had a feeling he might do that. I would’ve been more pissed off if I’d have spent six weeks on it like Chris Hughes did.

Chris Hughes: Paul played it to me, and I thought it was okay, although I couldn’t really hear the Trevor [in it]. It may have bugged him slightly that I didn’t go, “wow, great, important track on the album, fantastic.” Then later, I think probably when we were finishing up Motor of Love, he said, “you know, Figure of Eight, what do you think?” I said, “to be honest, probably the song with a bit of work could be better than the version that you’ve done.” He said, “well, yes, maybe that’s right.”. I didn’t know that it was rock ‘n’ roll to start with. I had no idea Trevor had done such a good job. I said, “it doesn’t feel it’s got quite the vitality. It’s not as vital as it should be. More band-like, more poppy”. I think he liked the idea of it being more band-like than what he ordinarily does. Then he called and said, “do you fancy having another go at it?” And that was it. I said, “I’ll give it a go. How far it gets moved from what it is, or whether it just needs a bit of energy in it, I don’t know, we can try it”. So we did sessions on that track. I think halfway through doing it, he said, “I’m really liking this, this could be a single”. And that was it. At that point I wasn’t going to go, “yes, it’s got to be a single Paul.” I didn’t play it up. I got on with it, really.

Chris Hughes: Paul played it to me, and I thought it was okay, although I couldn’t really hear the Trevor [in it]. It may have bugged him slightly that I didn’t go, “wow, great, important track on the album, fantastic.” Then later, I think probably when we were finishing up Motor of Love, he said, “you know, Figure of Eight, what do you think?” I said, “to be honest, probably the song with a bit of work could be better than the version that you’ve done.” He said, “well, yes, maybe that’s right.”. I didn’t know that it was rock ‘n’ roll to start with. I had no idea Trevor had done such a good job. I said, “it doesn’t feel it’s got quite the vitality. It’s not as vital as it should be. More band-like, more poppy”. I think he liked the idea of it being more band-like than what he ordinarily does. Then he called and said, “do you fancy having another go at it?” And that was it. I said, “I’ll give it a go. How far it gets moved from what it is, or whether it just needs a bit of energy in it, I don’t know, we can try it”. So we did sessions on that track. I think halfway through doing it, he said, “I’m really liking this, this could be a single”. And that was it. At that point I wasn’t going to go, “yes, it’s got to be a single Paul.” I didn’t play it up. I got on with it, really.

Trevor Horn: What a producer does is a service really. In a way, he’s in a service industry, he’s making the guy’s record. So it’s his record. Ultimately, if when I’m gone and if I’m not there and he wants it slightly different then [fine] make it slightly different. While I’m working on something I’m obsessed by it, the minute I finish and walk away I don’t pay much attention to it again unless under certain circumstances, like if I have to play it live, or something like that.

Chris Hughes: You get immune to it. When you start off, you’re quite precious about what you’ve done and your statement and what you’ve brought to the party. Across time, you get very relaxed about the idea that other people will take ownership. They’ll take it away and do what they want post-job. That happens all the time. The other thing is, in terms of producers, is when you’ve done a piece of work and it’s been sent back to the A&R department, or the label in general, most of the phone calls you get are in the negative. So they’ll say, “we like it, but is the hi-hat too loud?”, “Is there too much time before the first chorus comes?”, “Do you think you could fix those vocals?”, “We like it, but could you cut out the middle eight?” Rarely do you get a conversation which goes, “mate, brilliant job. Love it, not going to touch it. Thanks.” So across my career, there’s always been a lot of times when I’ve convinced people to do things a certain way and they’ve gone “okay”. Then you hear the thing later on and they’ve gone back and twisted it to kind of how they wanted it. My answer to that is similar to Trevor’s. You do what you do, and people like it or not.

Stephen Lipson: I had this realisation that one has to live life through a zoom lens, so when you are doing something, that is what you are doing. It is the all-important thing in your life at that moment, and then when you have done it, you need to zoom out and be dispassionate. I think that is probably the case for everything in your life.

Mitchell Froom: I worked with Neil Dorfsman on the sessions, and nothing was added to any of the tracks I worked on. But the one thing that’s different for me, that’s really unpleasant, is if mixes are taken away from you, and someone else mixes it, and they don’t understand what you’re trying to do. So I’m not a believer in that at all, this remix stuff. I think it has made music quite a bit worse.

Chris Hughes: I don’t know why Bob Clearmountain remixed the single version of Figure of Eight. I think Motor of Love went through some mixes and remixes too. I think Paul mentioned a few times that he was very aware that Neil Dorfsman was American. I think there was some sense of it sounding a bit more American, or something…

Trevor Horn: I thought we’d done pretty well, very short bursts and everything was good but if I’m honest, by I think by the time it got to Ou Est Le Soleil I’d been sucked into it a bit. I always see part of it was his personality, he was such good fun to work with him and he was so full of beans. But it sort of developed from a jam I think. I think Steve had a little bit of writing on it. Not officially, but I think he did.

Stephen Lipson: The night before, he said “well why don’t we come in tomorrow morning and just see what happens.” We came in the next day and he goes “anyone got any ideas?” I went “yes, I have”. I hit play on my computer and, forgetting the vocal and backwards guitar – [Steve plays the track from the start for about 50 seconds] – that came out from beginning to end. Which is why Trevor says what he said. And then Paul put seven words in French on one note on the top and said he had written the song, which actually, [as] he said it is lyrics and melody, you can’t really argue. I had a discussion with him about it and you know what… it worked out fine. I think I got an arrangement credit or something, and we did some deal. Whatever. But it is fine, he didn’t want to give me a writing credit and I think that is his prerogative. It would have been nice, but it is his prerogative. And it doesn’t make me think any less of the man.

Trevor Horn: You know I had a reasonable idea of how good, how much value a track had and something like Ou Est Le Soleil I’d forget about it [because] the problem with this one was always that it wasn’t a proper song. Really, it’s like a little piece of entertainment.

Trevor Horn: You know I had a reasonable idea of how good, how much value a track had and something like Ou Est Le Soleil I’d forget about it [because] the problem with this one was always that it wasn’t a proper song. Really, it’s like a little piece of entertainment.

Stephen Lipson: We didn’t spend that much time on it. I had it. It was all there. We over-dubbed a few things. I think he might have played drums on it. He got Hamish [Stuart] to play guitar and we might have developed one bit.

Trevor Horn: I remember Figure of Eight, but after that it gets a bit blurry. Rough Ride and Figure of Eight were just two sets of two days, that’s all that was and then I went back down because he took us out on his boat. I went back down and we spent like a week down there. How Many People is not really one of the best tracks on the album. This is probably one of my least favourites, I have to say, as a song. It’s a bit generic that’s the problem. Things had got a bit more long-winded as we went along, not necessarily for the better. I still thought Rough Ride was the best thing we did and I played it to somebody the other week and I loved it to be honest.

Stephen Lipson: I can’t even remember the song really. I don’t remember very much about it. [Stephen plays the song]. That chord [“never get a chance to shine”] is so ‘McCartney’! Those chords [“How Many People have died…”] that’s what we brought to the party. They’re from – remember Ferry Cross The Mersey, Frankie? – there’s a bit of that going on there.

Trevor Horn: On this, he started to play the flugal horn. At the start of it he could barely get a note out of it and by the time we’d been going for two days, he could get a tune out of it and he was sort of running around and he was just very funny. He even made me and Steve laugh because he’d run in to the control room and would blast out three notes and run out and do that kind of stuff.

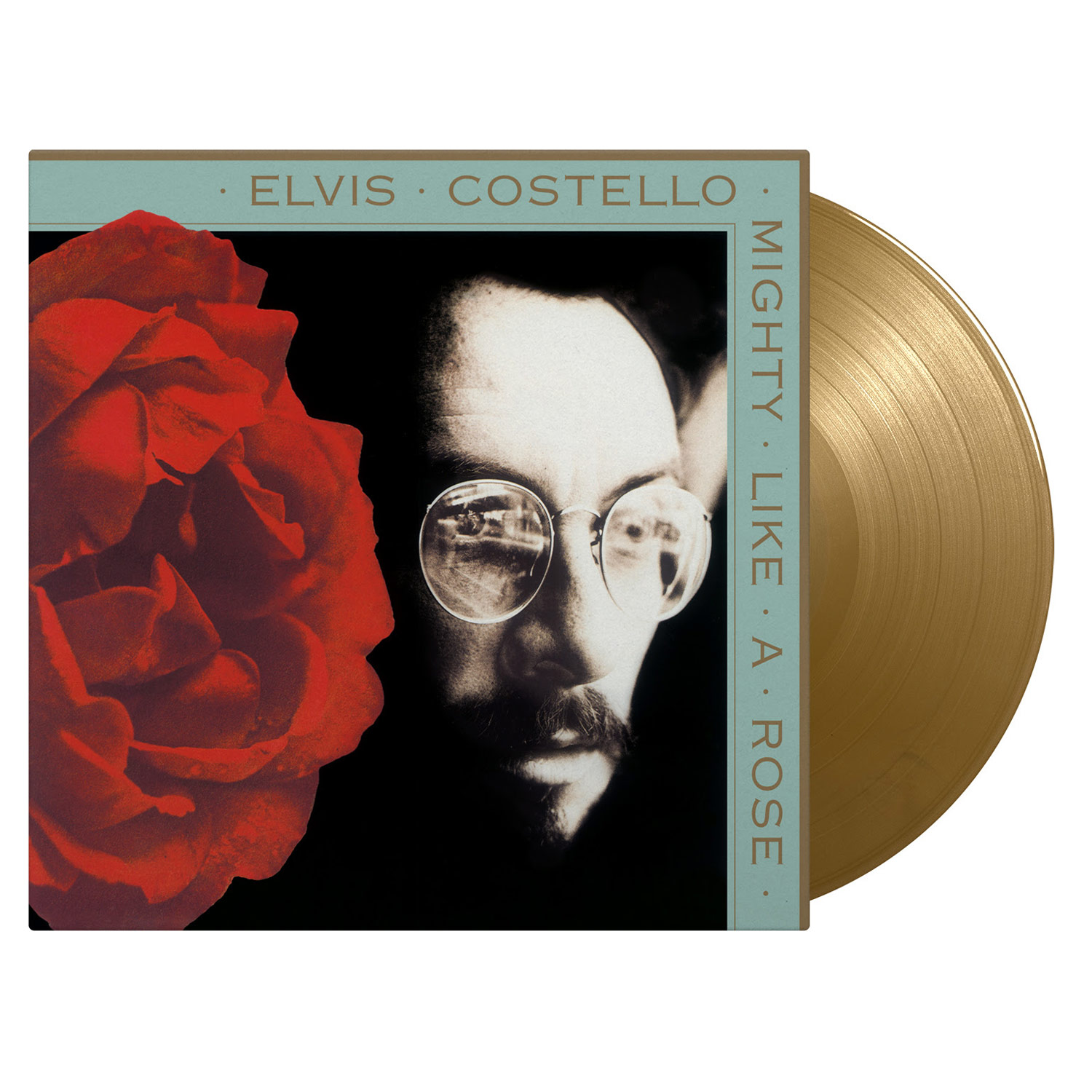

Mitchell Froom: [Me working with Paul] didn’t come from Elvis Costello, but I think Elvis endorsed the idea. Once the original sessions they did together weren’t going to pan out, I think he just moved away from it.

Elvis’s instincts were pretty strong, but not necessarily for the time period that we were in. That was the eighties, and the rough-and-ready kind of thing was not part of the culture, and Paul was always very interested in doing whatever he is doing of his time. And I think Elvis was trying to lean it more in a direction that would recall the sixties, which 20 years later, if that would have happened, would have been a very good idea. But at that time, I think Paul thought “I have done that before”, I want to be current, I want to do something that sounds like this time.

And also, Paul ended up playing on Elvis’s new record at the time – Spike – and so he was thinking well, Elvis’s record sounds more modern, so he wants me to sound old fashioned, and it just didn’t feel right to him. And I can understand it, I understand that instinct very well. In retrospect, the eighties is one of the worst times to be produced – aesthetically, it’s one of least pleasing periods, musical periods of time in popular music. And so it was difficult in that era, to do anything that just sounded good at all, but you wanted it to sound ‘current’, so it had all these contradictions just built into it.

The first sessions were Olympic, and I think it was two or three weeks working on them. And then there was a little break and he came to the United States and we worked on it for another week or so, and then we went back for the mixing. I think Neil [Dorsman] may have mixed the whole record, or most of it. So probably the whole thing was over a four month period of time, something like that, but yes. Also a lot of those sessions, as I think you know, but with things like That Day is Done and Don’t Be Careless Love, we just worked on what was already done from the original sessions with Elvis, those two.

Mitchell Froom: Well it seemed like it could be a hit. It’s a bit of an odd song in some ways, but it was really hooky, it had a great bass line, it was positive and a really cool lyric, great melody, it sort of had all that stuff. To be honest I have a hard time with the aesthetic of the period, it just sounds wrong to me. I would give anything to be able to remix it with somebody [laughs]. I remember hearing the music in a more raw form, and it sounded really good to me, and [at the time] when I heard this mix it sounded good to me because it was the eighties.

Mitchell Froom: I did a horn arrangement on on That Day Is Done, but Paul had already sung it, the drums were done, I think the backing vocals were done, some guitar – yes, we just fleshed it out a little more. I had this idea of doing kind of a silver band, a factory band English horn arrangement, and he just let me do it, you know? He had a few comments while we were doing it, but he said, “go ahead try it”. He is very open, and it was part of the thing, he already knew how to do all the stuff he had done before, and it was a different time. He is open for input and he just sees if he likes it, it’s that simple.

Mitchell Froom: Elvis Costello sang on it when they originally did it, but then came the notion of like “well, what if Paul does both parts, but we treat it in such a way where it’s like the voice in his head?” But when we tried it, it didn’t sound as good, so I think he finally just said “Let’s just get Elvis to do it, it sounds better”.

Elvis wasn’t around at all [during my work on the album] except for that day he did the vocal on You Want Her Too. But it was very friendly. There was no strangeness. Elvis understands as well as anybody that you make your record, you want to be happy with what you do.

The little intro part of this was from the original session, we just re-cut the song, except for the intro part. So that was a really good idea, that intro part, and I didn’t have any desire to try to recreate it or redo it, so we just used it, which was fine. I just remember that that was the one moment where I felt like I was working with The Beatles. There is about a half hour where Paul’s voice … we were tracking it live, and there was about a half hour in which his voice just hit that incredible raspy state, you know? And he just sang his arse off for a half hour, it was just amazing. But [we didn’t get it], for whatever reason – it was one guy messing up, or another guy – and those weren’t the Pro Tools days, and I don’t think we were doing it to a click. So it’s like if someone messes up it has gone. And so eventually his voice just kind of blew out

I was getting pretty angry, because I was [thinking] this is a simple song and we have got this guy singing and playing like this, can’t we please get this song, you know? But he was really easy going, he was just like ‘okay, well we’ll just get it tomorrow’. What is amazing for somebody else, isn’t to him because he is himself. We got the track I think the next day, but I’ll never forget that half hour.

Mitchell Froom: It’s an incredible vocal. The same with That Day is Done. There is a big reason why I didn’t want to even think about redoing those, because they were so good, those vocals. But yes, it’s a really quirky song, and I was surprised he ended up using it, but I liked it, for whatever reason.

I added drums to it, and don’t think this is credited correctly, but that actually was Jerry Marotta that played drums on that [credited to Chris Whitten]. I played keyboards; the Wurlitzer piano and organ. And I think we just worked on it, just added some extra guitar. It’s more like fleshing them out so that they fit in with everything else.

Chris Hughes: He sent over the tapes of Motor of Love, and back in the day it was two-inch tapes. It was basically “have a little listen to this, and see what you think”. I went to a studio in Fulham, I listened to the track, and I instantly thought, well it’s unfinished as a piece of writing. There’s no middle eight. It was somewhere between a demo and a master. But I made a copy of the tape and basically cut it at a certain point and put 12 bars of just time, just a little drum box in time, and glued it back together.

He came over to the studio, and this is the amazing thing… I said, “forgive me, but I think there is a middle eight missing here, it just feels incomplete. I’ve put a landing strip of 12 bars blank in the track, and wondered if you just wanted to try something out.” This was astounding. We plugged in a little electric keyboard, and he said, “ok, run it down”. We ran down the track, and literally, as it got to the blank bit, he started playing, and humming, and played it and finished it and rounded it off into the track. It was astounding, it was one take. Literally the second take, the second pass, he’d written it with the tune, and ten minutes, quarter of an hour later, he said, these could be the words. Honestly, it was astounding watching him create from absolute scratch and putting it in the track. That was for me, amazing. Anyway, he quite liked the fact it had gone well. Then we went down to his place, the Windmill, and started recording for real.

At that time, I had a Fairlight. So I was sitting there in the room with a Fairlight. He was funny, he was like, “oh, you’re going to quantize everything.” That was his kind of… because computers were coming in. He goes, “well, we used to just play”. I was like, “play away, but it’s the style and nature of things; I think it should be quite tight” and at the time, modern. That’s how it started, and he smiled and went along with it.

He’ll chat about the Beatles and tell you all sorts of stuff you shouldn’t know, private stuff. We used to do it like this, you know. He was telling me about when they recorded Michelle. He said, “well, you know, we came into the studio at nine in the morning, and I ran through the track with the lads, and we recorded it, we went off for a cup of tea, and Geoff and George had mixed it, it was put on the shelf, I never heard it again until it was out”. He’s really happy to tell me that actually, these things can be done incredibly quickly and incredibly easily. I’m slaving over a fucking Fairlight, which by nature is taking time, and it’s exacting, and it’s much more of a dull process. But, amazingly, he was fine with it.

Trevor Horn: Of course, he had the best Beatles stories, I mean just the best Beatles stories. I still remember one of his stories, which was how he found an old set list and in the middle, it said, “baa baa” and he was thinking what the hell is “baa baa” and then he remembered what it was. It was something John used to do where he’d get on the mike and he’d go a “baa, baa, baa, baa, baa baa black sheep..” and that’s all it was. He started out like he was doing Barbara Ann…

Chris Hughes: Motor of Love, even in its demo version, was alluding to being quite lush. It was slow and it was this slushy, lush ballad-y thing he was trying to get. We did layers and layers of Linda and samples and God knows what, as one did at that time. I listened to it the other day and I thought, fucking hell it’s so much of its time. That little place where there were string pads and synths and Fairlights and snare drums that went on for days, and snare drums being too loud. I think he was quite enjoying the nature of it sounding a little less like him and sounding a bit like some records that sound like that. The two or three things that are typical of him are the chord progressions [which] are Macca-y and his bass playing, as you’d expect.

The total time I spent with him at all was about three months, on and off. That was the window, and that included both tracks and other things. He went off to the Caribbean at the tail end of it, and was phoning me up and saying, “I’ve got a running order, what do you think, I’ll send it to you”. I changed the running order and said, “I really think side one should end this way, and it then leads around…”, and he was really great at the idea that there was some kind of artistry in the decision making. It wasn’t just a bunch of songs he would stuff in a bag and put out. So he was great with all that. I went up to Abbey Road and attended the cut. He would phone up and say, how’s it going, and all that kind of stuff. The whole thing was very relaxed.

Trevor Horn: I have to say, out of all of the legends that I’ve met, Paul was probably the least affected by it. You know, I’m sure that whatever he’s naturally like – and he’s naturally a bit bossy, he’s naturally a bit pushy – that’s his whole personality. But not to the point of being an arsehole or anything like that, it’s just his nature. I thought it was remarkable how sane he was considering what he’d been through and even not considering what he’d been through, he was still pretty sane. I’ve had people who’ve been through a gazzilionth of what he’s been through and they’re way more fucked up.

Chris Hughes: I wonder whether he feels he’s letting himself down by doing that little bit of – “do you know who I am?” It comes out every now and again. But I think he’s aware of it and I think he backs down from that prima donna thing. I could go on about other things that happened and things I witnessed. He was always great with me, fun, friendly and relaxed. I did see him getting tense and not quite so great with other people in his coterie.

Trevor Horn: He and I never had an argument. A few times I said things to him like, “Me and him don’t like rock ‘n’ roll”… that kind of thing. I would never get into an argument where somebody was saying, “I’ve done lots of it, so I know better than you”. It’s not a good productive thing. Those are the arguments that you can never win. But is sometimes said to producers out of frustration. It doesn’t help, but you know it might help them get through their frustration. That would be the best way I could describe it.

Chris Hughes: The funny thing is you hear his voice and you hear him singing, and you can’t disassociate if it’s any good or not, you just hear it as a bit of Macca, as a thing. He’d done a couple of vocals which I was listening to it thinking, it isn’t great. It’s kind of okay, but not… and I was saying, “well, the energy’s not there, you need to get some pressure in your voice, it needs to be…” – I was hearing myself, thinking, I can’t quite fucking believe that I’m telling him this.

Chris Hughes: The funny thing is you hear his voice and you hear him singing, and you can’t disassociate if it’s any good or not, you just hear it as a bit of Macca, as a thing. He’d done a couple of vocals which I was listening to it thinking, it isn’t great. It’s kind of okay, but not… and I was saying, “well, the energy’s not there, you need to get some pressure in your voice, it needs to be…” – I was hearing myself, thinking, I can’t quite fucking believe that I’m telling him this.

Mitchell Froom: He is not defensive at all and there was no mind games or anything like that. I don’t get involved with things like this, I don’t challenge people, you just work on the music right, you don’t play mind games? But I remember where he was trying to replace a bass part that we already had, and he tried, and I just listened for five, ten minutes, and I just said “Well I think what we have is better”. And then he would say ‘Let me try one more’ and then it would be spectacular. So there was this side to him that liked the challenge, yes. And part of me thought it was a bit odd, but you don’t want to go down that road with someone, criticising them, so that they will do something better. But in general, he could certainly rise to the occasion and maybe sometimes, a little bit of that, helped him.

Chris Hughes: Because he’s so good and can do something relatively quickly, and it can be up on its legs and making sense – I think there’s an element that he can be lazy in terms of him being great. Well… the song’s good, now I’m going to do a fucking amazing arrangement and amazing performances. Some of his records, his headspace, you get the impression that he’s doing it and it’s all right, and it makes sense, and it’s Press to Play. There’s other times where somewhere, someone’s obviously said – or he’s thought – “actually, this might as well be great”. Definitely, getting Elvis in [was a good idea] – somebody who wasn’t just going to blow smoke up his ass. Elvis is a tough character to work with. I think he quite enjoyed the game being raised. I think it shows.

Trevor Horn: I was very careful about who I liked to work with, you know, I always have been. You go into a studio with some people and they’re not very good or they’re hard going. But Paul was like… he’s the kind of guy if you had a song and he was around I’d have him in the studio, he was so good. He was just good at everything, good drummer, good bass player, good guitar player, good singer and full of fun and lots of ideas. You know ideas just coming out of them and it made me think, Jesus, I bet they were all like this, I bet all four of them were like this. Well, he was probably the most like that.

Stephen Lipson: He is just really good. That is the bottom line. He is great. My overriding thought was I couldn’t think of a better person to be in a band with. That is what I constantly thought. He is just really good at everything, and also he has endless ideas.

Stephen Lipson: He is just really good. That is the bottom line. He is great. My overriding thought was I couldn’t think of a better person to be in a band with. That is what I constantly thought. He is just really good at everything, and also he has endless ideas.

Mitchell Froom: He was very down to earth; really a kind, thoughtful person and funny. So on that level, sessions work the best when everything is kept pretty casual, so it certainly was that. But it’s Paul McCartney. I’ve worked with some famous people and you can’t get around it, particularly when they start to sing, or in his case play the bass or play whatever. And it’s very different if you’re in the room with someone [rather] than if you hear it later on the recording, it’s a very different experience, it’s one of the things I like most about my job.

Stephen Lipson: McCartney, like a very few other people I’ve worked with, is what I would consider a clear thinker. His ideas can flow very easily from that subconscious out of the building, which is not a definition of genius, it is a definition of someone who can think clearly without a sinus infection of the brain. I loved every minute of it. It is not right to say it will be a high point because everything is a bit of a high point, but it was seriously memorable, that is for sure. I came away not necessarily that fond of him as a person but with far more respect than I thought I had to begin with. I mean, huge respect for him. I won’t hear a word said against him really.

Trevor Horn: I enjoyed it, I enjoyed meeting him and it gave me an insight into what it must’ve been like to have worked with The Beatles, which I think would’ve been great fun, you know. I only ever met him and I never met any of the others. What are my memories of it? My memories are of Linda. I’ve still got the photographs she took of me and Steve, I’ve got them up on the wall downstairs. I suppose the main memory was it’s nice when you meet somebody that you grew up with – I was into The Beatles from 1963 and Love Me Do right the way through to the end, every album played to death, you know. It’s nice to meet them 15 years later and find that they’re nice people and you like them.

If you enjoyed this feature, it is available as a ‘keepsake’ printed edition.

Interview

Interview

By Paul Sinclair

106