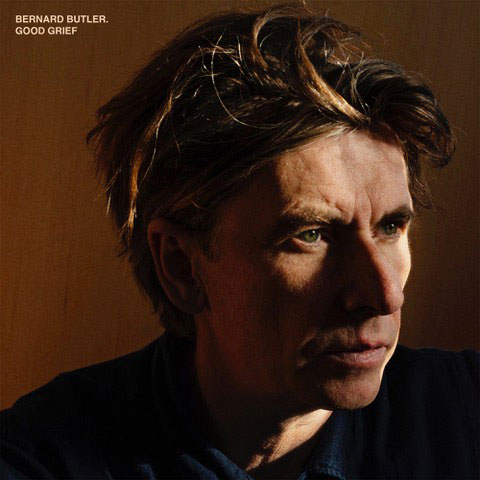

Bernard Butler: The SDE interview

Butler discusses his new album, Good Grief

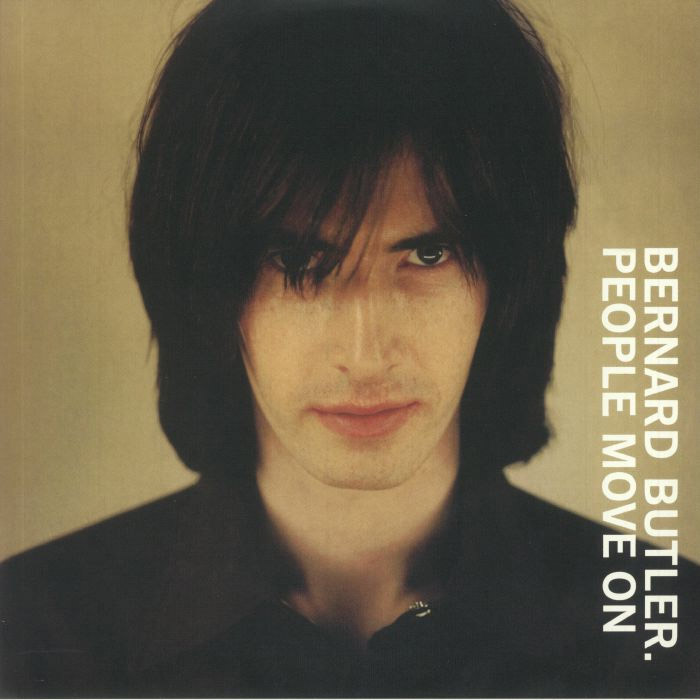

It’s been 25 years since Bernard Butler’s last solo album, 1999’s Friends and Lovers – the follow up to his debut, People Move On, which was reissued in 2022. Rather than forge ahead as a solo artist, the former guitarist with indie-glam rockers Suede has made a name for himself as a producer and a collaborator – he’s worked with acts including David McAlmont, as one half of the duo McAlmont & Butler; Pet Shop Boys; Duffy; Sharleen Spiteri; The Libertines; Tricky; Sophie Ellis-Bextor; Bert Jansch; Ben Watt, and Sam Lee.

In 2022, the album he made with actress, Jessie Buckley, For All Our Days That Tear The Heart, was nominated for the Mercury Prize – during the writing and recording of that record, Butler used certain techniques and processes that then informed the writing and recording of his long-awaited third

album, Good Grief, which is released this month. SDE caught up with Butler recently to discuss the new record…

SDE: Let’s talk about the background to the new album. The last time I spoke to you was ahead of the reissue of your first solo record, People Move On, in 2022 – you re-recorded the vocals, added some guitar parts, and put out a new version of it on Demon Music. You told me that prior to that happening, you’d been going into a London rehearsal room in Holloway Road for 18 months, with an electric guitar and a microphone, revisiting some of your old songs, and then you started writing some new ones. So, Good Grief is the result of that?

Bernard Butler: Yeah – absolutely. That’s funny because you were at the other end of the process. Part of it was doing what I did with People Move On and doing the reissue – Demon asked me to do it, and I thought I would re-record the vocals.

At that point, I’d been playing, going into rehearsals and trying to rethink… I was playing the [old] songs, recording them on my phone, listening back to them and thinking, ‘Oh, God – this is really different…’

It’s quite hard to judge when you listen to it once – I really need time to get a good perspective and trust how I feel about something. Over a period of months, I realised what I was doing was quite consistent. My voice has changed, but it’s not so much that… I’m a different person, and your mind tells you to behave in a different way, which comes out in the way you sing or perform.

As you get older, you feel more free – I started singing in a much more free way to make myself happy. I was letting myself be myself. So, when the question of doing People Move On as a reissue came up, I took the opportunity. I thought, ‘If I do this and I feel good about re-recording the vocals, then I know I’ll be really confident about going forward and doing new songs.’

So, how quickly did the new songs come together? Was it a fast process?

It’s funny – I keep thinking about when I wrote these songs, and I can’t remember… I should look it up. It was over a period of time… There were quite a few that happened during COVID – before I met Jessie Buckley. When I met her, everything changed overnight and I thought, ‘Woah – I’m just going to do this…’

It developed quite quickly with her, so we had a load of songs and I just sort of pursued that. I didn’t really care about my own record – I thought, ‘I’ll do it whenever,’ and I’m glad I did that.

That project lasted for a couple of years, and I carried on writing on my own during that period. The record with Jessie took a long time to get together because there was a period when we wrote songs, and then she went off and did a film or something, and I wrote songs on my own.

I had to convince her to record the album because she didn’t want to do it – from the project ending to it being released was about four months, but for me the whole process was about two and a half years. The processes I used when I was writing with Jessie I carried on with for my record.

She’s got a co-write on the last song on Good Grief, which is called ‘The Wind…’

Yeah – when I met Jessie, she sent me a lot of text. I wouldn’t call them lyrics, they were just lines of words. I think she was in Toronto doing a film – she would text me all the time. Not even ‘Hello – how’s it going?’ – just reams of text that were kind of meaningless and very abstract. I grabbed a few of those and turned them into a song called ‘The Wind’. We blotted out that song completely – we didn’t use it or go back to it. When I was doing my record, I just kept singing it for myself and I finished it off. The opening few lines are Jessie’s and the rest of it is mine, so that’s why she’s credited on it, because she started the idea.

There’s also a co-write with Edwyn Collins on the track ‘Clean,’ which is a song from 2001…

That’s right – I wrote it with Edwyn in 2001. It was a B-side – no one ever heard it, but I always really liked it. When I went back to playing in the rehearsal room, I tried to remember songs and that was one of them that I played over and over.

I really enjoyed it and I felt it had a more profound meaning – it’s one of those songs that’s carried itself over time and has a different meaning now, which songs often do. I ended up recording it again – I wanted a different version of it.

Why did you call the album Good Grief ?

The title is a reference to the fact that I’ve experienced grief in the past year of my life – I don’t really want to discuss that specifically.

We all experience grief, but when someone mentions the word it’s like you’ve mentioned ‘the war’ or something… There’s something slightly ludicrous about it – it’s the only inevitable action that will happen to every one of us in our lives, and yet, we still find it difficult to address and to deal with when it happens, and it can be quite farcical at times.

We forget that grief happens to us – not the person that’s died. It’s about how we cope in the process and afterwards. The record isn’t about that at all – there are no songs referencing it – but the title came to me because when I was recording and finishing the record last year, it [grief] was going on in my life, and I just felt it was important to underline ways of grief happening to you that could be positive or inspiring.

The only way to deal with it is to see it in a positive way. That’s what people who we’ve lost want us to do – to go forward with our own lives and shine a light.

The other side of it is that a lot of the record deals with emotions… It’s just something that’s always been portrayed as a weakness of mine, and I was always branded with it – that I was an emotional person, and I was sensitive. I always thought that was really unfair – to brand someone as emotional when we’re all emotional as human beings.

When I was a young person that definitely happened to me, and it was something that I hid and felt ashamed of. I’ve addressed that on a lot of the songs on the record – being able to deal with emotions, and how all of us try to cope with our everyday lives and the darkness and the sadness that we face.

There’s a song called ‘The Forty Foot’, which is about a place in Ireland, near Dún Laoghaire, in Dublin, which is where my parents are from. We went to Dún Laoghaire every year on holiday – we went to see relatives for a few weeks.

It’s a rocky cove, where people go to dive in – a freshwater swimming place. It’s very famous – people go there on Christmas Day and New Year’s Day. There’s a pool for people with mental health issues. I liked the idea of people going there every day to dive underwater and save themselves – obviously there’s such a religious background to that, and in my life.

A lot of the record is about being OK with having emotions and turning it into a positive. Instead of saying, ‘You’re a bit emotional,’ I’m saying, ‘Isn’t it a good thing that you have emotions.’

Instead of saying to somebody, ‘Oh – you’re too sensitive,’ how about saying, ‘Isn’t it nice you’re sensitive.’ Do you know what I mean? It depends how you frame these things, and too often in my life it was framed as something I should be ashamed of. I’m just trying to reframe it.

The weight of the title encapsulates those feelings of trying to restage the idea of emotions, and I like the fact that the phrase ‘Good grief,’ is something I use all the time. It’s like a Carry On phrase…

For me, there’s a lot of self-effacing comedy in the lyrics. I chuckle at some of the stuff I’ve done and written, and I know what it’s referring to, and it’s not that serious.

You mentioned emotions – there’s actually a song called ‘Deep Emotions’ on the album. Was the title inspired by a quote by Sylvia Plath [ ‘I don’t know what it is like to not have deep emotions. Even when I feel nothing, I feel it completely.’]

I didn’t take it from that, but I read afterwards about her saying that line. I wasn’t sure about what to call the song – I thought ‘Deep Emotions’ might sound like the title of a cheesy Rose Royce song from 1978 – but when I read that Plath had used that phrase, it made me feel OK. She was talking about the same thing – that it’s OK to have deep emotions in your life and to display them. That’s why I allowed myself to use it.

I like the way the song starts, with an acoustic, folky, Bert Jansch-like intro, and then it builds into a mini-epic, with a string arrangement and some great, soulful electric guitar. What inspired that song musically?

I don’t know – I just started playing. There’s a lot of acoustic playing on this record, partly because, on the Jessie Buckley album, I was playing a lot of acoustic guitar, and I got into open tunings an awful lot. That spilled over into this record.

My wife bought me a guitar for my 40th birthday. It’s really lovely – a ‘50s Gibson LG. I kind of loved it, but I hadn’t really used it that much – then when I did the Jessie record, I fell in love with it. It just felt like, ‘Wow – this is what this was always for… it was meant to be for this.’ Now it’s the thing I play all the time – it’s like finding a pair of shoes… it takes a while to get used to them, but, suddenly, you can’t take them off.

I got into the guitar and started writing everything with it, so that’s where that intro came from, and, obviously, Bert was a big part of my life – not just musically, but also personally. He was a profound influence on me.

One of my favourite songs on the album, ‘Living The Dream’, sounds like it has a Spanish guitar on it, and it features whistling…

Yeah – my first whistle. You can tell I’m of a certain age and I really don’t care anymore… You think, ‘Oh, I’ll just whistle…’ You would never do that when you’re 22… [laughs].

In some of the songs, you reference suffering from insomnia and bad dreams, and in ‘Living The Dream’, the title of which has a double meaning, you sing: ‘When I was 17 and living the dream, it’s not what I thought life was gonna be…’ What was life like at 17?

The song has a dual meaning… It is about the fact that as a middle-aged, old codger it’s easy to think how brilliant life was back in the day, when I could do anything, but, actually, my life is really great at the moment. I’m really grateful – it’s astonishing. I’m amazed at how things have turned out for me – I never thought I’d be making music for a living. When I was 17, I dreamed of it, but I never thought I’d do it.

When I was 17, I thought I was Roddy Frame. I used to watch Aztec Camera videos, and Roddy would have double denim on and look super-cool. He was stick-thin and he was a brilliant guitar player, and I thought, ‘Wow – I wish I could be somebody like that.’

That time in my life was really great – I was absorbed in music, and I didn’t do a lot of socialising. I went to gigs, but I wasn’t a teenage player, going out with girls or in gangs – I did my 10,000 hours of music, music, music, which got me here.

I’m amazed at how things have turned out for me – I never thought I’d be making music for a living

Bernard Butler

I’m addressing that thing… It’s so easy for middle-aged people to say, ‘It used to be great back in the day,’ and, of course, I’m referencing me as well – how people constantly reference my own back catalogue, and say, ‘Wasn’t it great back then?’ I’m just trying to throw it back, and say, ‘Live where you are – be in the present for once in your life, and let me live in the present,’ because it’s way more profoundly enjoyable than it was 20 years ago.

That’s a nice segue, because in the lyrics of the song ‘Pretty D’, you say: ‘Well, it’s been 20 years since you broke my heart, oh, 20 years, we’ve been falling apart. Am I losing my touch, baby? Why don’t we start it again?’ Is that a song about getting a fictitious band back together?

Yeah – kind of, but it’s more of a love song. It’s easy to read music into it because it’s me, but it’s really a relationship thing…

If you know The League of Gentlemen, it’s the Les McQueen and Crème Brulee thing – the terrible sadness of him just standing there [when the rest of his band fail to turn up for the reunion tour after he’s given them money to go back on the road]. It’s bang on the money. We’ve all watched it and thought, ‘Oh, isn’t it tragic?’, but we all want our musicians, our artists, our actors, our models or our footballers – anyone we admire – to always be the person they were on the day we first encountered them. We don’t ever want to see them fat or bald, or grown-up and doing something different, and we can’t accept it. We’re so harsh, but we don’t think for a second what we look like…

It’s plagued me, it still does to this day, and it always will – I’m just trying to throw it back at people. We cannot cope with nostalgia in the right way…

You see the story of the character in ‘Pretty D…’ He’s me – I’m playing the protagonist and I’m being very self-deprecating. We always say, ‘Oh, that was so bad, you broke my heart, and I can’t bear it anymore – let’s do it again…’ In so many relationships, people just can’t move away… they haven’t got the ability to say, ‘That was great, and now this is different…’

There are a few religious references in some of the lyrics on the album. In ‘The Forty Foot’ you sing about trying to escape the troubles of a Catholic mind, and there’s a song called ‘Preaching To The Choir…’

My upbringing was very strictly Catholic – quite hardcore. Lots of the Irish who came over [to England] in the ‘60s were pretty lightweight about it. Where we grew up, in North London, everyone was Irish basically, apart from a few Poles. This was in the ‘70s, when there was a bit of a shadow of shame about being Irish – we were told to not advertise it, because of the Troubles.

We always had priests in our house – my mum spent a lot of time at convent and my dad was part of a Catholic men’s organisation. I was an altar boy, and I was incredibly involved with the church – I went to an all-boys, Jesuit secondary school. By the time I was 16, it was like, ‘Great – that’s over with.’ It was an overwhelming thing, but you stop going to Mass as soon as you can.

When I left home, I had nothing to do with the church ever again – I couldn’t be more of an atheist if I tried – but I know I carry the weight of it – the classic Catholic guilt and sense of shame.

When Neil Tennant wrote those lines in ‘It’s A Sin…’ the whole first verse of that song… it was like, ‘Oh my God!’ It was so astonishing that he wrote this damning piece, and it was a number one pop song.

Let’s talk about the recording of the new album. You made it at your own studio, 355, and you produced and mixed it yourself. It was mastered by George Shilling, who worked on the original version of People Move On, and the reissue. How did you approach Good Grief ? Did you know what kind of record you wanted to make and what it should sound like?

At various points… I would probably have liked it to have been much more minimal [laughs]. I started off playing the songs on one guitar and singing, but one thing led to another, and because I hadn’t made a record on my own for a long time, I just started to shape things and see how they turned out together as a group. I was quite inspired by the Jessie record. I played an awful lot of my record on my own.

Drums, bass, guitars, piano and violin… I didn’t know you played violin…

I played violin when I was a kid – until I was 14. I gave it up to play the guitar. I can’t play the violin really, but I wish I could, and I wish I’d kept it up.

I do have a violin – when I was doing the Jessie record, and because it was COVID, and I wanted to hear some sounds, I got one and started to make some John Caleesque noises and scrapes on it. I played drones and layered them up – I really enjoyed the sound of it. There’s quite a bit of my [violin] playing on ‘Preaching To The Choir’, and also there’s a guy called Jo O’Keefe, who plays [violin] quite a lot.

You worked with string arranger and violinist Sally Herbert too…

Yes – Sally and Ian [Burdge – cellist] did the strings on ‘Deep Emotions’ and ‘London Snow.’ Sally is a good friend of mine – I’ve worked with for so long. She played on ‘Yes’ back in the day, and she just knows me really well.

‘London Snow’ is another one of my favourite songs on the album. It has a majestic feel and, again, it’s a track that builds, and it has a big orchestral sound…

I didn’t intend it to be like that… I can clearly remember writing it during COVID, and it’s very much about London – obviously I was stuck in London at the time… My wife is a teacher, and she was working in a school in the city – I can remember going down there quite a lot during COVID, because her school was open, and she could go in as a key worker.

We both cycled from North London into the city, and I can remember those days when it was just a ghost town – this place that’s usually full of people everywhere. There was something beautiful about it.

The idea of ‘London Snow’ is all the layers – the homelessness, the people who’ve gone missing… They’re all in London, under this layer of sadness – frozen over.

It’s the cliché of London – people not talking or being friendly when you get on the Tube, and beneath all that veneer there’s an emotional tension all the time, everywhere go you. All that sadness and poverty is hidden.

You’ve made a Dolby Atmos mix of the album available, but only on streaming platforms…

A friend of mine is a guy called Myles Clarke, who works at Dolby – he was charged with promoting Atmos a few years ago. He came to me when I was doing the Jessie record, and said, ‘Do you want me to help you to do this?’

I hadn’t heard of it at that time, so we did the Jessie record in it and that worked out great. Since then, I’ve just kept track of how it’s working out and it’s quite interesting – the trajectory of Atmos and where it works and where it doesn’t.

I’ve interviewed some producers, including Stephen Street, who aren’t fans of it, and see it as a bit of a gimmick…

I don’t like the idea of putting a barrier against any part of my work – if I think I’ve done that, then it’s my instinct to say, ‘You’ve just stopped yourself doing something, mate – why?’ You should question yourself, and I think all of us who do creative things should question why we don’t want to find out about something.

I was curious about it – I like learning about stuff. If you don’t want to hear it, you can listen to the other one. I don’t really have a problem with it – why not just give it a try?

I get it – the drawback [with Atmos] and Stephen has probably seen this… To get old records into Atmos, you have to remix them to stereo first – you have to get back the stereo mix before you can separate it into Atmos.

A lot of it is happening – a lot of people are doing it really well, and a lot of people are doing it really badly. That’s the problem. Whereas, if you’re doing a new record, and you’ve just finished the mix, it’s very simple to just separate the parts of it into different speakers.

Whenever you hear Dolby in a cinema or at Dolby in Soho Square, you can’t help but sit there and think, ‘Oh, wow – that sounds good…’

AI is another hot topic in music which divides people…

So much pop music sounds like it’s made by AI already… robotic and everything to a definite click. There are no dynamics and it’s all exactly the same structurally and texturally.

I don’t really mind it [AI] and I’m not scared of it, because people like me, making mistakes in rooms, telling bad jokes to audiences, and forgetting my setlist… that’s not for AI. You can’t compete with me, I’m afraid. [laughs]. I think that’s a good thing – people will pay to go out and watch something and be around human beings, as part of a community, and to be in a room together.

Part of AI is… if you go and see some megastar at a mega-dome and pay £700 to do it, and you stand staring at a screen that’s 200 metres away, and the sound is pretty bad, and you can’t see anything… People come away and complain about it, and every venue in your town is closing down… The figures are just horrendous – the money that’s being made by the big corporate agencies and the promoters… It should be going back into saving grassroots music venues.

People complain: ‘My son or daughter has to go to this show because everyone’s going at school’, and you’ve just spent £400 on tickets and you’re so depressed by it…

What is wrong with you? Fucking pull yourself together and stop doing it, because people like me are out there and trying to earn a living.

Some of the venues that I play all around the country are so welcoming, they treat you well and they work unbelievably hard – the venue creates the atmosphere and the night, not the lights, the songs or the dance routines. The venues create that feeling of community that is so needed. The moral is that AI will take over all of that and arenas – you make your choices in life…

I came to see you do a solo show at Esquires in Bedford, in December 2021, at which you played some new songs. I can remember hearing ‘Camber Sands,’ which was the first single off the album, for the first time, and really liking it, but I was very surprised when I heard the studio version – it’s turned into a mini-epic. It reminds me of Springsteen, but more M20 motorway than ‘Thunder Road…’

Quite a few people have mentioned Springsteen, which is really funny, because I don’t think I sound anything like Bruce Springsteen…

You don’t, but it’s the atmosphere of the song, the way it builds, and the idea of escaping, and the road trip in the lyrics…

Yeah – I don’t normally like references and stuff like that – ‘You sound like this…’ but I like that one because I’m so far away from being Bruce Springsteen as you can imagine, for obvious reasons. But I like what you’ve said, and I read something recently in which somebody was talking about how Americans like talking about the road or the great road trip, and they like geography – it’s a common thing in blues or folk – but the English have a real problem being able to discuss our own geography and dropping in place names [in songs.] You can talk about the great, wide open highway or Highway 61 and stuff, but nobody wants to drop in the M11…

Billy Bragg did ‘A13 Trunk Road To The Sea,’ which was a piss-take of ‘Route 66…’

Yeah, and of course, he’s a big fan of Americana-folk – he understands that influence.

Listen – I’m a Londoner and I’ve never left here. Whenever there’s a weekend or a break, we always head for the coast as quickly as we can – just for a day trip. We look at where we can drive to and back in a day – a couple of awful hours on the motorway, or going through the Blackwall Tunnel, and we’ll get there.

When you get there, all you want to do is to stand on the beach and look at the sea. I always look at people there who are also just looking at the sea – I always think it’s such a profound thing… All the distractions we have in life, but people can just go and look at waves and be speechless. That emotion… I wonder what people are thinking about when they’re looking at waves and harbours.

One of the places I’ve regularly gone to is Camber Sands – it’s not the only place… The song isn’t about Camber Sands at all…

It’s a love song, isn’t it?

Yeah… There are other places on the coast – Hythe, near Folkestone, that I really like. And Mersea Island, in Essex, which I really love and I go to a lot. That gets referenced in the song as well.

Have you ever been tempted to move out of London?

Yeah – we always go to the coast, and we think, ‘This is brilliant, why on earth do we live in London? This is so beautiful – we could sell-up, buy a farm and get a speedboat or a horse’ [laughs]. I think, ‘I could have a studio in a stable…’

You think about it, but then you go home and forget about it. That’s essentially what ‘Camber Sands’ is about – that feeling of ‘Why do I always come back to London? What is it I’m doing?’ What I’m doing isn’t really about the seaside, it’s about the journey – trying to leave yourself and leave your past behind…

To promote the new album, you’re playing some solo shows in record shops across the UK in May and June, and you’re touring too, including a gig on the Acoustic Stage at Glastonbury. There’s a big sound on several of the new songs – can you envisage doing some gigs with a full band?

I went to the London Palladium on a Saturday night to see Nerina Pallot and she played a beautiful show with a massive band, with strings – it sounded amazing.

I thought to myself, ‘If you’re going to do this, do it that way, and if you can’t do that and make it sound good, then just do it on your own.’ I don’t like the halfway house of making it sound like a cheap version of the record, and I really enjoy playing on my own. Whenever I perform now, I don’t want it to be like, ‘Oh – it’s just me…’

It’s a powerful thing to take a song into its purest place and improvise – I can kick-off a song how I like, and I can finish it how I like. If I want to do a solo, I can, or if I don’t… You feel the room and you can really perform to the people in front of you. If you’re doing a band set, where everything’s quite disciplined, it has to be the same every night, regardless of who the audience is.

I just walk in and try and feel who they are and judge how I perform. I change the songs – a lot of the setlist is improvised. I can play what I want, when I want – it’s good and I’m really enjoying it.

Your new album is the first physical release on your own label, 335 Recordings. Any plans to put out records by other artists, or is it just a vehicle for your own music?

It’s a vehicle for my own music, but we’ll see what happens… It’s funny – when my label was announced, I had a deluge of people asking me to sign them.

I think they got the wrong end of the stick… As if I’m going to dish out advances… I haven’t got an office complex… It’s an imprint for my music and it feels like it’s a beginning – putting out records will be an ongoing thing. This is the first one, and it’s exciting to think of what I can do now I’ve got this platform.

It means I don’t have to go to a record company begging to get my demos played or to be held to account for commercial success – I’ve made hundreds of records and I just feel like I’ve done enough for other people. I deserve to not feel nervous about putting out music, and I don’t really care about the success element of it anymore – it doesn’t really bother me.

It’s 25 years since you put out a solo record. Are you not worried about what people think of the new album?

I can’t be – it’s just part of the nature of everything. You’re damned if you do, and you’re damned if you don’t. The internet makes it a harsh place. I’ve read some things which people have said already… They’ve got a piece of music, which is five years in the making, for free, heard 15 seconds of it, and couldn’t wait to get on their keyboard… If it’s not for you… I can’t imagine who that person is who jumps on their keyboard to have their say…

I’m not trying to compete with Radiohead or Beyoncé. I just want people who like what I do to appreciate that I try really hard, and I have done for 35 years

Bernard Butler

For me, when I want to have my say about something, I write songs and I make a record. People don’t have a clue how much of an effect they’re having on you – the possibility of actually stopping you from working and the potential of stopping someone from creating something in the future.

It’s not just me and it’s not a new thing – it’s always been like this. I’d like to say that I don’t give a fuck, but of course I do – I want people to like it – but, at the same time, I’m not trying to compete with Radiohead or Beyoncé. I just want people who like what I do to appreciate that I try really hard, and I have done for 35 years. I just want a break…

Can you tell us about any other projects that are coming up? Are you producing for anyone?

There’s no producing at all going on – I’ve not been offered anything [laughs]. That’s the truth of it. It’s a hard environment, but that’s fine.

The only other thing I’m doing is with Norman Blake and James Grant. We’ve done some shows as a trio and we’re making a record – we’ve written pretty much most of it and recorded it. That will be out next year.

They are diamonds. I love being around them – it’s like being on a little holiday. They’re so supportive of me and that’s been a big part of me doing this [the new solo album], as I started singing again with those two. It didn’t all rely on me – it relied on their songs as well.

I love their music and their voices, and they made me feel really comfortable and confident about performing. I owe them a lot. Whenever I see them, it’s really relaxing and good fun.

Finally, is there anything else in your back catalogue that you’d like to reissue? After the first McAlmont & Butler album, and People Move On, what about any other McAlmont & Butler releases, your second solo record, Friends and Lovers, or The Tears album?

Somebody asked me about that [The Tears] a few years ago… [that’ll be SDE, Ed.] I don’t know what happened about it. I know that at some point, we’ll do the second McAlmont & Butler album, Bring It Back, and we’ll do the record that we never put out – we had a bunch of songs that we never finished. We never recorded it properly and it fell apart. It’s just sat there – once a year, I’ll have a quick listen and think, ‘God – somebody should hear this at some point.’ I’d love to put it out – that’s on my list.

Thanks to Bernard Butler, who was talking to Sean Hannam for SDE. Good Grief is out now, via 355 Recordings.

Compare prices and pre-order

BERNARD BUTLER

Good Grief - black vinyl LP

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Compare prices and pre-order

BERNARD BUTLER

Good Grief - CD edition

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tracklisting

Good Grief Bernard Butler /

-

-

- Camber Sands

- Deep Emotions

- Living The Dream

- Preaching To The Choir

- Pretty D

- The Forty Foot

- London Snow

- Clean

- The Wind

-

Interview

Interview

SDEtv

SDEtv

By Sean Hannam

14