Graeme Clark on Wet Wet Wet and Popped in Souled Out’s 30th birthday

Wet Wet Wet bass player ‘pops in’ to SDE to discuss the band’s debut

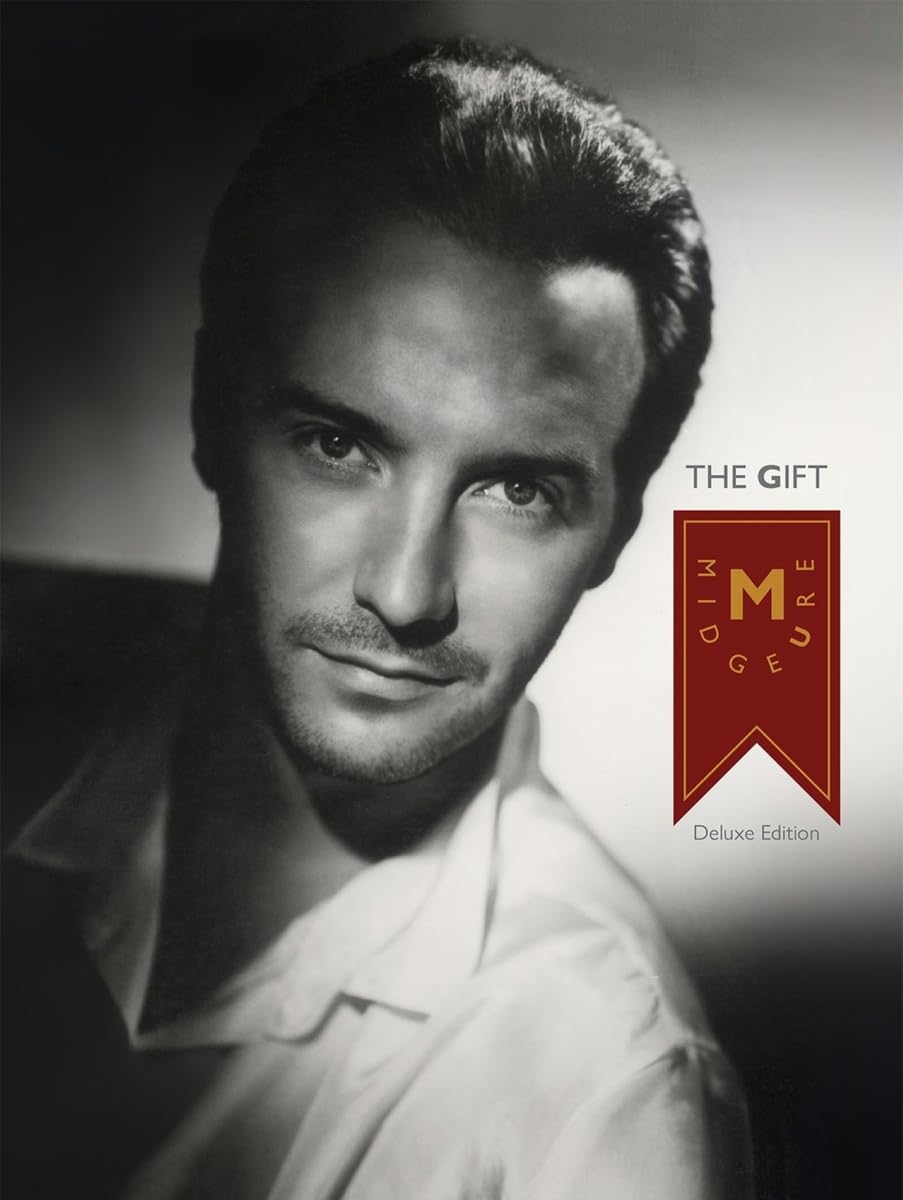

Universal Music have recently reissued Wet Wet Wet‘s 1987 debut Popped In Souled Out as a rather impressive five-disc super deluxe edition. SDE recently caught up with bass player Graeme Clark to reminisce about the band’s beginnings, the early success and to ask why Marti Pellow has recently left Wet Wet Wet at what should be a time of celebration…

SuperDeluxeEdition: Every band is going to have some sort of back story in terms of how long it took them to get where they got to and all the rest of it, but the Wet Wet Wet back story is particularly long and drawn out, isn’t it? It’s from the very early 80’s through to ’87.

Graeme Clark: Yeah.

SDE: Were there times when you just thought ‘it’s not going to happen’?

GC: Aye, yeah, that was pretty much on our radar at all points, even when we signed a big record deal. You’ve got to remember the time as well, I think we signed at around about ‘85/’86 and to the record company’s credit, they said to me “Go away, write your songs, we’ve invested in you and you can go on a tour, you can go and find out who you are. You can go and figure out who ‘Wet Wet Wet’ are, go and write some songs and make your mistakes.” If you think about that and leap 30-odd years in the future, the comparison is let’s look at ‘X Factor’ when you’ve got eight weeks of Saturday night telly and if you’re not Christmas number one man, you’re out, it’s end of story. So it’s a totally different landscape and I don’t like comparing because it’s a bit like comparing footballers, ‘is that time better than this time?’ you can never do it because it’s not comparable. But yes, we did it so many times, the album, we started it, we got producers in…

SDE: I was really interested in the fact that you nearly got signed to Rough Trade, Geoff Travis. That could have taken you down a different path in terms of how the record company would have promoted you, because Phonogram, they were a major label, they wanted to present you in a certain way, but that wouldn’t necessarily have happened with Rough Trade.

GC: No, it wouldn’t, and I must admit, coming from where we did and coming from where we did musically, it’s well documented in that book [in the super deluxe edition of Popped In Souled Out], we were all in our own little kind of worlds and my world, my music world was the world of independent music. Record companies like Rough Trade and I remember The Raincoats and the The Slits and John Peel sessions. I was lucky, I had an older brother who was like three or four years older than me, so I was getting drip-fed from his record collection, and he would have been 16 when I was like 12.

So I had access to the music that I wouldn’t normally have gravitated towards or even been listening to, so just sort of indirectly, it’s kind of there in your house and you’re hearing these things. Scritti Politti, he was a big fan of them and he used to order these records that would come back in these sort of strange do-it-yourself kit, so I had access to all that sort of stuff and it just made the record companies … especially these ones, they made them much more interesting because it was much more accessible to a wee guy in Glasgow; Phonogram and Mercury were all a bit of a mystery. So when I first went down to London to take our early songs to record companies, we were going to guys like 4AD, you know, Rough Trade… We did go to majors as well, but we didn’t really have a clue, and ironically, we went to Phonogram, and [laughs] I don’t know if that even made the book, but we went and sat in the office and the guy said “Look man, if you’re going to come in here and play stuff, you need to go to better studio and do a betters demos man, because you cannae listen to this.”

SDE: What was wrong with the demos then? They just didn’t think they were polished enough?

GC: Yeah, I mean they were the early incarnations of like Angel Eyes, really early, there was an early incarnation of Sweet Little Mystery that bears absolutely no resemblance. But there were a couple of lines from it that survived, but really, we were finding our feet. I can’t blame the guy, you know, at the same time, we did have Marti, who was an unpolished diamond, at that time, and really when Geoff heard it, he was the only guy that played the song twice and went through and sort of said “Look man, I’ve got an idea about a record label” and it turned out to be Blanco y Negro, I don’t know if you remember that?

SDE: Yeah, I do…

GC: And it was always the idea that Geoff had spoke about, was to be part of that and that was quite exciting for us, as 17 year old guys, having a guy like Geoff Travis who seemed to be quite interested in what we were doing. I think what he did see, when he saw the pictures, I think he saw Marti is a pretty decent … having a really good voice and being the good-looking guy then. At that time, Rough Trade were going through … they’d done all the ‘do-it-yourself’ records and they were haemorrhaging money, weren’t they? So they had to look for things that were going to be able to sustain that kind of record company model. And a way of doing that is to find some commercial success, so I can see exactly why Geoff kind of thought ‘oh, this is interesting’. And I’ve always had respect for that, for Geoff, he did come up and see us in Glasgow and I liked him, I really liked his ethos, I liked his record collection man, you know what I mean.

SDE: Yeah, and he’s an original, proper music guy…

SDE: Yeah, and he’s an original, proper music guy…

GC: Exactly, and that’s the kind of guy that you want to show some sort of … but that was really, for me anyway, to get a guy like that interested in you. I just thought ‘well, we must have something man, there must be something there, because this guy has got credibility, he’s got kudos, he’s got the records to back it all up, he’s not just bluster’.

SDE: So even though that didn’t work out, it wasn’t necessarily a big negative, because it gave you some sort of confidence…

GC: Well, I think so, I think definitely. We went down lots of times and yeah, it was great to have somebody like that, definitely good, yeah. There’s one person that believes in it, and it’s a cliché, but it’s true man, you know, if you can convince one person and they sort of start believing in it, then it’s almost like you’re convincing yourself as well and kind of going ‘well yeah man, what I believe is right’. Because let’s face it, we all have niggling doubts, even to this day, every moment of every hour, there comes a doubt into your head as ‘am I right here, doing that?’ And you’ll put it out there but in the back of your mind, you’re going ‘oh, I don’t know if I’m right about this’.

You have to form the belief system and it takes guys like Geoff to kind of back that belief system up and you sort of fluctuate from being … there’s no in-between and there’s no measure of any kind of partiality. You’re either the best band in the world or you’re the biggest piece of shit that’s going… you know what I mean? It’s like there’s no in-between ground when you’re in a band. I think that translates to all sorts of different parts of life, but I do remember being 16 and 17 and having that pressure from your peers saying “Are you sure? Are you really sure about this?”And you’re kind of going “Yeah, yeah, yeah” and then in the back of your mind going ‘I’ve absolutely no idea man’, you know, anything could happen.

SDE: That must be a lot of parents’ worst nightmare though, their kids saying “I’m going to be a rock and roll star”…

GC: [laughs] Well, I think it’s more of a career choice nowadays, you know. I think, back then, for sure man, it was a different. Thank goodness for the Tory government and the 80’s man, you know, because there were no jobs to be had where we were. So it was a fairly austere time, politically and financially, so we went right on the dole and that was a ticket out of there really, because we could spend all our time or as much time as we wanted devoted to try to find that song that’s going to take you out there.

SDE: Although those sessions you did, the demo sessions, with Wilf Smarties around 84/85, they seemed to be like a turning point, those ones that have ended up on the demos disc in the box set.

GC: Yeah, I think it was. I think it was just finding your feet in the studio and we’d been in a few different types of studios and worked with a few different people, but when Wilf came along man, he kind of … he reinvented the studio for us. He made it a place… studios can sometimes be quite sterile, quite sort of austere environments and are not the most inspiring of places. But we went down to Wilf man, he is an eccentric guy, he came from a completely difference place from anyone we’d met before and it was just that enthusiasm, not just enthusiastic but creative. And he made the point of saying to us “This has got to be creative, but it’s got to be good fun as well man, we’ve got to have some sort of … we’ve got to emanate something that looks as if we’re having a good time in here man” do you know what I mean?

And I totally related to Wilf, I totally got where he was coming from and I just thought ‘that’s exactly what we need’ you know, not have the pressure of, let’s try and write this really big, massive hit single that’s either going to make or break us. The reason we started in the band was one, we wanted to be interesting to everyone else and two, we wanted to have a bit of fun man, you know, and kiss some girls… and I think a lot of people would join bands just to do specifically that. So we were no different, but when we started having fun, that’s when we thought ‘do you know what, this is what it’s about’ and through that, it kind of frees up all that stress that’s maybe there and ‘oh God man, we need to write a song’ you know. I always felt we had the ingredients of something pretty good between us all and all we needed was the song that was going to kind of carry us out there. And luckily, we had a few of them man, when we look back.

SDE: What’s interesting is, the version of ‘Wishing I Was Lucky’ that you did with him, it was the version that came out, with a few tweaks.

GC: Yeah, it was and well it does, and to be fair, we were … it’s something that doesn’t really happen nowadays, but we worked on the songs, we kind of wrote the song and then it kind of morphed, sometimes in the studio, sometimes in the rehearsal room. But I don’t really see that necessarily happening with a lot of people nowadays, I think it’s just the general turnover of music now is just such that it’s like people see there’s no point in doing that. But we demo’d Wishing I Was Lucky lots lots of times man, but we ended up going back to the original demo, we did it again with Wilf and it was radically different.

But it kind of caught us, the sort of … there’s this indefinable … and I hate using this word, but there is indefinable ‘x-factor’ that nobody can say why one version is better than the other. If we knew that formula, we could bottle it and use it again, but for some reason, there’s just certain songs that, when you do them, you capture a moment. And I remember going in and working with Stephen Hague who made the Pet Shop Boys’ first single and he drummed it into us that … he came in at the beginning of the recording session and said “Guys, this demo here is better than some of the songs in the fucking charts at the moment man” and I think what he was saying was, ‘fucking hell, I’ve got my work cut out to try and make this better than what’s already there’.

And try as we did, you know, we wanted to be better and the fact of the matter was, it wasn’t, it had elements that were maybe a better, but I think, overall … the fact that we went back to the original demo and worked on that and took that a stage further and then used the nucleus of what was there.

SDE: But I noticed the Stephen Hague version, there’s nothing in the box set, was that just because it wasn’t different enough or you just didn’t think it was worth putting on?

GC: Well, we ended up doing a radical ‘Metal Mix’, that’s the Stephen Hague version, although Walter Turbitt, who was a big hitter at the time, he did the sort of remix of it. So that is a different version, although to be fair to the demo, lots of what went on in that demo gets sampled from …

SDE: I see, yeah, I’m looking at the credits now actually, so yeah, you’re right, that ‘Metal Mix’, it is actually credited as produced by Stephen Hague but then additional production by Walter, yeah, that’s right.

GC: Yes, that’s right, well Walter just took it and kicked it in and stuck that big, like heavy metal guitar in it, which really kind of make it … I thought it was a great version, but if you look at the Stephen Hague version, it didn’t have that guitar and it was, basically, a re-make of the demo where, when we couldn’t reproduce what was on the demo, he re-sampled it and stuck it in there. And it seemed out of context in a sense man, it was like ‘yeah, theoretically, all we’re doing is re-creating this thing again and the theory is, it should be same. And because we’re in a bigger and better studio with a bigger and better producer and a bigger and better budget, it should be better’, but it wasn’t. And there was a lot of resistance within the record company to Wishing I Was Lucky as well. I think it’s easier in hindsight, isn’t it, you kind of point the finger and so I’d say I think we were all trying to get to the same place.

SDE: What did they think… why were they resisting that? Because I would have thought that was the obvious first single, what were the record company thinking then?

GC: Well they just didn’t think it was accessible, they just didn’t think it was going to get played on the radio and they didn’t think it was a strong enough song… we went down and had lots of meetings with them. And I remember one specific meeting where we took, what we felt, was the finished song and said “Look, you’ve got to listen to this, you’ve got to listen to this” and they never. That was the point of kind of no return really where there was a fall-out between the way it got A&R’d and management and us and the way that we saw us and the way that they saw us. I don’t really know what they thought we were, because, as I say in hindsight now, Wishing I Was Lucky … I think it’s one of our best songs because we meant it, do you know what I mean? It’s like it’s true man. And as they say, usually when it’s the truth, it’s usually your kind of best stuff and I think it’s one of our better songs. I’m not sure if it’s the best, but it’s certainly up there and I think, as an introduction to who we were, I thought it was perfect.

SDE: You guys were proved right in the end because it was obviously quite a big hit. But when you were talking about the A&R side… it not working out with Dave Bates, who’d obviously worked with Tears For Fears and people like that, did that relationship break down when he was trying to get you to work with John Ryan [US record producer who’d had success with Animotion]?

SDE: You guys were proved right in the end because it was obviously quite a big hit. But when you were talking about the A&R side… it not working out with Dave Bates, who’d obviously worked with Tears For Fears and people like that, did that relationship break down when he was trying to get you to work with John Ryan [US record producer who’d had success with Animotion]?

GC: Well yeah, there was a whole lot of things, it wasn’t kind of one particular thing that broke our relationship, there were lots of disagreements in the way that we should have been presented. And the fact of the matter was, even at that time, if you remember, Tears For Fears were making huge, big … there was that big production, wasn’t there, Frankie, Tears For Fears, Songs from the Big Chair, all those. So we came in with what was our ‘massive production’, which was basically a demo of a song we’d recorded in Edinburgh and I think for a lot of people, that obviously became quite a sticking point. Don’t get me wrong, if you look at some of the Tears For Fears records man, they’re really, really brilliant, ground breaking kind of production and really great songs. So in a way, no one was right and nobody was wrong, it was just it was our call, wasn’t it, it was our shout because it was our band.

SDE: And also, things take so long to develop. I mean what sounds great in ‘85/’86 isn’t necessarily going to be right for ‘87/’88, is it?

GC: Well in those days, it moved fast and the technology moved fast and so that’s the thing, it’s happened over 30 years, the little circles have got smaller and smaller, but in the ’80s you were in that technology-driven studio environment. The technology was being driven by guys like Trevor Horn who want the big sound…

SDE: So let me ask you this then, because what happened next seems to contradict everything you’re saying, but whose idea was it to do ‘The Memphis Sessions’ and go off with Willie Mitchell, then? Because that seems like the opposite to what you kind of should have done.

GC: No listen, I think that was just a kind of …

SDE: Was that band-driven? Was that you guys saying “We want some heart and soul in our music”?

GC: Yeah, it was. You’ve got to remember as well, we get asked “Who do you want to produce you?” and we’re all sitting kind of looking at each other, but did we say “What’s a producer?” because you don’t want to be in the record company kind of asking the wrong questions man, do you know what I mean? And we were sitting going “What the fuck is a producer do?” and so, of course, you go back and look at all the records you like and Willie’s name kept on coming up. And somebody, our publisher, Jill, had said “Well, there’s only one way to kind of find out about these people and let me put the phone call in.” And, of course, she phoned them up and she said “Look, he’s quite open to come and at least meet you” so of course, to ask 21 year old guys “Do you want to go and meet this legend, this soul producer, in Memphis, in his studio?” it was like ‘yeah, we want to work with Trevor Horn, but fuck, Willie Mitchell in Memphis sounds a wee bit cooler to me man’.

And so yeah, it was an about-turn and I think it was an amazing thing to do. Never in our right minds was it ever going to kind of go out there and be the release that Mercury were going to go with, because they just felt … Willie has techno-fear. And I remember Dave Bates coming to the session and throwing around things, he said “What you’ve got to do is, you’ve got to strike the tape with SMTP and, of course, Willie is just kind of looking blankly at him, like “Look man, that’s not really how I make records, you know.” And Dave is trying to kind of bring it into the 80s, Willie is kind of steeped in the 70’s, he’s got techno-fear, he’s not used to any kind of level of technology… we didn’t even use click tracks man, it was just a case of ‘one-two-three-four, go’.

Now that, in me, at that time, we’d went in and worked with a couple of big producers and this was a complete breath of fresh air. Yeah, maybe, at the time, you could look at it and say “Oh, it was quite a backward-looking album really, when you think of all the technology that you had and you made that album.” For me, I think the test of time is that we now look back on that album and it’s got a sound, for me, we made a lot of albums but that was a true album in as much that we made it in six weeks in the same studio. It can be argued that it’s one of the few albums that we actually made where, when you talk about albums being made in the one place with the one producer at the same time and mixing it and putting it out there, then that was kind of completely finished and topped and tailed in six weeks.

SDE: And I’d always assumed that the band all loved that and the record company said “We’re not releasing that”, but the book seems to suggest it wasn’t quite as clear-cut as that and you maybe were a bit more divided within the band, some of you loved it, some of you thought ‘it’s good, but it’s not going to work as our first album’.

GC: Aye, I think that’s fair to say. I’ve skimmed the book so I’ve kind of got a look at what we were saying there.

SDE: Because Marti, in particular, I think what I took from what the book says was that Marti kind of really liked it, but the rest of you might have been a bit more unsure as to whether this was commercial enough.

GC: Well, I would dispute that fact man, that Marti stood there on his own saying “Hey guys, this is great man.” I think, just for the record, I loved it and I think what I was trying to say maybe in the book … and it just depends how it’s been interpreted, I would say that he thought there’s no way that the record company are going to release this because it just doesn’t have that Capital FM, ’80’s kind of radio sound, and I stand by that with him. As I said to you there, for me, it’s the only album we ever made in terms of we made it at the one time, I love that album.

I’m biased, because I can see the value in doing something like that, that wouldn’t necessarily equate to commercial viability. I can understand why a record company would say “Do you know what, we want a nice, big shiny product that’s going to go out there” other than trying to kind of lay the band down as a credible R&B kind of set-up man, I can see why they wouldn’t buy into that. For me, it made perfect sense to do Popped In Souled Out and then release the Memphis sessions as The Memphis Sessions and if we’d had the success that Popped In Souled Out had, you would have a lot more ears on it, with the Memphis thing …

SDE: And that’s what ended up happening in the end, didn’t it?

GC: Yeah, exactly.

SDE: But it’s crazy though, when you think about it, and I guess it’s just a reflection of the money in the music industry in the 1980s, but they kind of sent you out there. How long were you out there for, six weeks or something?

GC: Yeah, six to eight weeks, it was a couple of months man.

SDE: So that’s, obviously, an investment. You come back, they go ‘this hasn’t really worked, let’s do something else’. Obviously, they haven’t got a bottomless pit of money, but they were willing to spend more money. It’s almost like the more they invest in you, the less likely they are to drop you because they’ve spent so much money.

GC: [laughs] I think you’ve got a good point there. Now yeah, there were elements of being dropped and you kind of thought that …

SDE: Were you worried? When you got back from Memphis and they said “We don’t like this”, were you thinking ‘oh shit, we’ve blown our chance here’ kind of thing?

GC: Well, you do think that, but we had a pretty shrewd manager who said “Listen, that’s the greatest thing in the world, if we get dropped, we’ll walk into another deal.” And that was the kind of swagger that we had in a sense man, that we were confident that we’d walk into another deal, because the thing about the two years, we learned to play, we learned how to craft in the studio as well I think. So although maybe the commercial kind of song, we didn’t know if we had that yet and really, I think to Phonogram’s credit, they would … they did have a bottomless pit of money, that was the beauty of the record companies back then, they were slamming money and getting like… and that’s the irony. They never saw what was coming in 10 or 15 years down the line. And so the internet came along, they just never had the nous … record companies were big and dumb man, they had all this money seeping in everywhere, all over the place. And you just felt it’s too big, it’s big corporate conglomerates man, and of course, yeah, we had that hanging over our head ‘are they going to drop us?’ But you know, I think we were too good to let go as well, we were sort of a better version of Curiosity Killed the Cat, you know what I mean.

SDE: And you ended up with Michael Baker, doing quite a lot of tracks with him – how was that? Because I think the work he did with The Blow Monkeys was quite processed; drum machines and all that, and you managed to avoid that and it still sounds quite organic. But how was it working with him?

GC: It was great man, I loved it, I loved Michael as well. Michael was very much from the Wilf Smarties kind of school of thought, he was insane and he ran the sessions like that, he used to sleep under the mixing desk, he wouldn’t change for weeks on end, his clothes. He was eccentric and that’s the kind of guy that you want, that was the kind of guy I liked having around the studio and pulling this record together that was a difficult record to make. So we had the perfect balance because you had Michael who was the eccentric guy who got the vibe and the studio together so as you could play these songs in a way, and then you had Axel [Kroll] who was the kind of cool, German guy who came from a musical background and could arrange songs in a way and present them. And yeah, as you said, the Blow Monkeys, I loved those records, I thought they were great, but yeah, they were very of-the-time, if you listen to them now, they sound a bit thin and a bit 80’s, and you’re like ‘oh right, okay’.

SDE: That’s what I think, but your record doesn’t sound like that and it’s the same producer but he … it must have just been a different dynamic?

GC: He did, that was the clever part, wasn’t it, it was like ‘yeah okay, let’s look at the band’ and if you get real drums and real players and all that, then it’s not going to be too machine-orientated. There was a couple of machine tracks and you can sort of hear them in there, I Don’t Believe (Sonny’s Letter) is a bit … it’s got that kind of electronica, kind of machiney-type thing, you know, there’s a bit of that in it. Also in Sweet Little Mystery, there’s a little bit of … you can hear the sort of 80’s thinness there. But the band’s in there, so that kind of pulls it back, so you were really … because nobody knew what the fuck they were doing back then, you know, you were trying to utilise the technology but not lose the essence of the band, man, that was the trick.

And it brings me round to that… we did a Stock Aitken Waterman version of Sweet Little Mystery and we never put that on there because it did … we had internal arguments about that, because I thought it should be on there, right, but the argument and the band line was it’s too much like Stock Aitken Waterman with a Marti vocal. And I don’t know if I agree with that, I think it should be on there because …

SDE: I can completely understand that argument, but given that you put the John Ryan stuff on there, which isn’t really what you wanted either, I think, just because this deluxe set is going to be the last word on this record, in my opinion, you should have put it on, just for the sake of satisfying the curiosity of the fans. They’d probably listen to it and go ‘yeah, it is a bit shit’ and that’s it.

GC: Exactly, exactly, and listen, I agree with that, I totally get what you’re saying there and I had to…I got stood down man, you know.

SDE: Because you got out-voted, yeah.

GC: Well [pause, laughs] it was a dictatorship, I have to say, that voted me out, you know.

SDE: But how did that even happen anyway? Did someone at the record company just sort that out without even asking anyone at the time? Who approved Stock Aitken and Waterman even doing it, back in the day?

GC: Well, this is what you did, you released a single and you did a 12-inch remix and actually, it wasn’t Stock Aitken Waterman as such, it was one of their programmers.

SDE: Okay yes, probably, Phil Harding?

GC: It was a Phil Harding remix, yeah, it was a Phil Harding remix. Now, believe you me, I even think the record company wanted it because they said “Look man, Phil Harding is a cult figure and you’ll get people buying it just for the Phil Harding kind of remix.” So there was a commercial call for it as well, and these things … and in a band dictatorship, democracy, sometimes you have to tow the line man, so I’m told.

SDE: Just before we talk about ‘Wishing I Was Lucky’ being a big hit and all that and then the explosion of success you had, tell me about [guitarist] Graeme Duffin. What have you got against him being a member of Wet Wet Wet? [laughs] Because it’s always been ‘Wet Wet Wet plus Graeme on guitar’, how come he was never a member of the band?

GC: Well, it’s one of those things, isn’t it, it’s one of those… we went to Memphis and we used the guy from Memphis, so I think, at that time, and you’re going back 30 years, we were pretty much… Graeme was the guy, the ‘go-to’ guy in Glasgow and we went to him, he played the gigs, he was part of the band. But it just felt like we were going to get a new guitarist all the time …

SDE: But he ended up hanging around for a long time.

GC: Well that’s the thing, isn’t it, he always says that “I’m the new guy and I’ve been here for 35 years, man” you know what I mean?

SDE: But was he quite relaxed about it? Was he ever petitioning you, saying “Come on, make me a member”?

GC: He’s not that type of guy that would … he just doesn’t have that kind of ego that would force himself upon us. And I do feel that it’s the one thing that, out of everything, it should have got addressed properly and he should have been kind of brought into the band and been a full member. At the same time, I think as well, Graeme had a young family back then… he was a good bit older than us, he didn’t come from the same area. So in a way, even back in those parochial days in Glasgow, if you come from the other side of the river … it’s not unlike the way London is, I guess. If you’re north of the river man, you very rarely venture south and if you’re south, you very rarely go north man, do you know what I mean? So although we stayed ten miles apart, it was a big kind of chasm, and yeah, it should have been addressed and he is a member, whether we like it or not, he is part of the band man, no doubt about it.

SDE: Tell me about appearing on ‘Top of the Pops’ for the first time, because is that like proper sort of childhood dreams coming true? That must have been amazing.

GC: Of course it is man, we were recording the album and, of course, the single is climbing the charts and that’s boyhood dreams as well, you’re like ‘oh my God’, it’s now two years after signing a deal, things are rosy in the garden. And just to top it off, the record company say that you’ve got Top of the Pops. If your record moved up the charts three consecutive weeks in a row or something silly like that, then you got Top of the Pops and we went in… I can’t remember, I think we went in at number 39 and they said “You’ve got it this week.” And you knew that if you went on Top of the Pops, millions of people were going to suddenly see you man, your face was just going to be public property.

We went on Top of the Pops and we were in the BBC, the ‘doughnut’ studio in White City and it’s just like this unbelievable experience. We do the dress rehearsal and Whitney Houston is there singing I Wanna Dance With Somebody and you’re tapping a wee finger on the microphone in time to the music and we’re just all fucking blown away, we’re just all fucking can’t believe it. The record company have brought four bottles of champagne in and suddenly we’re on this crest of a wave and it’s like ‘right, let’s see where this takes us guys’.

SDE: And you ended up going on the show, like, six or seven times in that early period. You must have been bored by the end!

GC: Not at all man, we were just happy… you’re sort of thinking as well, at that time, the average length of a band’s career in the charts was like three years man, you know… so in the back of your mind, these niggling doubts that I spoke about in the beginning of the interview, you’re like ‘this is our one and only hit single maybe’ do you know what I mean? Yeah, “Do you want to do Top of the Pops?” “Absolutely” “What again?” “Yeah, absolutely man.” You just don’t know when it’s going to end and if you come from the west of Scotland, there’s this mentality that you’re always… I always thought something is going to sabotage this, something is going to happen and it’s not going to happen.

And I thought ‘maybe we’re just destined not to happen man’ because there were lots and lots of bands that never happened, better than we were, and maybe had better songs than we did, do you know what I mean? And also it wasn’t beyond the realms of possibilities that, for one reason or another, it wouldn’t happen.

SDE: And were you living in Scotland still at the time? Were you going up and down to London, like a yo-yo?

GC: Yeah man, we were flying about, life was fast and we were here, there and everywhere and it was great, when we went back to Scotland, you were a sort of fucking folk hero up there man, in terms of ‘local boys do good’, we were kind of loved and hated in equal measure. For everyone that loves you… and I think that’s just the way life is, isn’t it, no matter what you do, if you do something and put your head above the parapet man, people are going to love you for it and people aren’t going to love you for it, that’s just a simple fact of life. Having that working-class background, it kind of saved us in a way, it put a perspective and a spin on it for us that you were like a fluke man, you know. You kind of try and strive and sort of get there and then you sort of have this good kind of grounding because you’ve been brought up by good people and I think that’s safe to say about everyone in the band. We had good people around us, our parents and brothers and sisters and all that sort of stuff.

SDE: So you didn’t go too crazy then, because…

GC: …No, no, I’m not saying that, no, we did go crazy, of course we did, but…

SDE: Because one thing that’s really apparent is, is just how quickly everything exploded. I mean you did the tour with Elton John, you did the Lionel Ritchie thing, you did some really big things very, very quickly. And mentally, did everyone stay with their feet on the ground, more or less?

GC: What do you think man? Of course we didn’t, no, we were working class guys and we knew in the back of our mind ‘look, this is crazy, this is complete insanity’ but we were milking it for all we were worth man, it was such an amazing time. And you had to be blasé, because fucking hell, Elton John has just came in the studio man, and I say this, it’s lucky we’re not dogs man, because Elton is coming in and our tails are wagging and we’re trying to kind of go “Oh fuck that … alright Elton? How are you doing man?” So all that and you’re trying to not be over-awed by your circumstances and sort of saying “This sort of thing happens every day of our life man, Elton taps our dressing room door and says “Hello”” and of course, you’re sitting there going “Fucking hell man, what the fuck is going on?”

SDE: But does it ever get any better than that? Because obviously, you did have some big successes later on, but did it ever really ever get any better than that initial hit of …

SDE: But does it ever get any better than that? Because obviously, you did have some big successes later on, but did it ever really ever get any better than that initial hit of …

GC: Well, I think you just learn to live with it man, you know, to me, it was always exciting, going and doing Top of the Pops, yeah, but there were times when you’re blasé about it. But when you kind of think about what you’re doing, we were in Capri, we were getting the private jet, drinking Champagne on the way to Top of the Pops, again, you know what I mean?

SDE: Yeah, what’s not to like?

GC: Well, when I look back on that, it almost seems like a parallel universe that you’re travelling in. Because at the end of the day, you go back to your house and you have to be yourself man, and you have to be with yourself. That’s the difficult part, is stepping off of that fucking mad roundabout that’s swirling around at speed and trying to acclimatise into some sort of normality, and that was always going to be the difficult aspect of it.

SDE: How do you view the record, 30 years down the line, I mean as an album? You’ve obviously got quite a bit of distance between now and then.

GC: Aye, it’s a really good question because I kind of fluctuate. Sometimes I think I can see things that I wouldn’t allow to happen today with the songs, but as a standalone piece of work, I think it’s great, I think it’s a pretty good introduction. And really, the way we were thinking about it was, when I speak to the lawyer that did the record deal back then, he said “I remember doing this deal and sort of thinking ‘wow, these guys have got a lot of money spent on them and they’ve signed a big deal’ blah, blah, blah. Okay, they’re making an album, but if this album doesn’t make it then at least they’ve got a chance of making another album and maybe that might hit.”

That was the kind of mentality and I think, to an extent, I think we thought that as well, that maybe it would go out and be received well and then you would go on tour and then you would be a working band and then it would take time. But as you said, that all got pre-empted in the space of like six months, because it was just like this tidal wave man, where you’re just like ‘my God man, this has just taken off’. I think because Glasgow had the City of Culture thing, suddenly we were poster boys for that, so that kind of pushed us on there and so all these kind of little things came together at the one time.

SDE: But the thing about it was, it was sustained, wasn’t it? Because you didn’t have one big hit and then have two or three minor hits, you had three or four big hits in a row.

GC: It did man, it did.

SDE: And the record company must have been delighted, in the end, that their investment in you, in terms of the time and those two years trying out different things, it all kind of came good, didn’t it?

GC: I think they were. Obviously, when things are starting out, there was shaky ground that we walked upon with the record company, but I think once we get out there and once we’ve figured out who we were and once the public figured out who we were… I think Mercury were really good to us as well. I think it was a good match man, you know, it was a good pair-up and seemed to work really well. I guess there’s all that pressure for them as well. No matter who you are, if you have a major record release, it costs them a million quid to set up the promotion, to set up the record, to set up everything properly, they will be spending the best part of a million. And when you’re spending that sort of money, then you’ve got to make sure that you give it every possible chance, I think.

SDE: What about the process of going back and getting together with everyone and working through the old tapes and putting together this re-issue? How involved were you and did you enjoy that process?

GC: Well, you know, it’s a bit of a love/hate, because it does flag up a lot of stuff, it brings a lot of stuff back to you man, you know, and don’t get me wrong, most of the memories were like what we spoke about, the meeting all the profile people and all these fantastic things it seems to create. But there’s obviously other bits that weren’t so good and I listen to some of these old songs that… you know, when you’re starting them off, sometimes they’re not the greatest of songs man. We’re at the coalface, do you know what I mean? And everybody’s hearing the end product and the end result of all the manifestations of all the different kind of incarnations of the songs… so we’ve kind of gone back and exploring that.

Some of it was great and some of it … like that John Ryan stuff, that was a bit painful to listen to, for me, because it was kind of … I must admit, I played it to my son and he’s like “Oh dad, that’s brilliant man, why didn’t you release that?” and of course, he’s a child of the 90’s. So he looks at the 80’s like this kind of halcyon period, do you know what I mean, and he’s sort of grown up with Never Gonna Give You Up with Rick Astley and stuff like that.

SDE: But why was that specifically painful though? Was John Ryan trying to do computerised bass and all this kind of stuff? Was it just an unhappy time because you felt sidelined or something?

GC: Aye, I mean basically, this was a classic ‘let’s get a producer and make the record guys’ and ‘hey listen, you don’t even need to be there because I’ve got this big phone book here and I can phone…[anyone]” “Hey, who do you guys want to sound like?” that was his question to us when we first met him. Even in my arrogance man, that was an alarm bell ringing for me, what does it mean here? Who do we want to sound like? I thought it was quite … you know, even then, and I think I say this in the book, it was like we were copying people, we were trying to copy Al Green, getting it totally wrong, but ending up with something kind of totally unique in the process man.

So even back then, I kind of remember ‘oh yeah man, we’re sort of trying to copy Otis Redding here, but we’re nowhere near it, but we’re getting something that maybe sounds like us’. So with that John Ryan stuff, I just remember being in the studio and being put in the position where he’d wanted to produce a song that we had called I Remember and he reckoned that that was our big song. And I remember, in the conversation with the record company, with John Ryan in the background and me on the phone to the guy in the record company and the producer listening in to my conversation, and Dave Bates is saying “I know it’s kind of hard for you to talk, but is this working out?” And I’m trying to be diplomatic at the same time as well, it’s kind of knowing that this is all wrong in my head, this isn’t really working. And it was like he was a phone book and if you wanted to make a record like a Frankie Goes to Hollywood or something like, you know where you get the boys in, then that would be the guy that you would maybe go to. But for somebody like us who was like … yeah, we wanted to be part of that process, we wanted to be part of making the music and making an album and making the records and writing songs, you know, and being part of the production, but it just seemed to me that… yeah, you’re right, I was being sidelined. And, of course, you imagine that coming back to the record company ‘oh, the fucking bass player is on the phone here fucking saying that this producer isnae right, the guy who thinks he’s the producer in the band’, do you know what I mean? So I could see …

SDE: But they must have, in the end, respected the feedback from you and the band. They didn’t sort of say ‘tough shit, if it’s not working, we’re not going to try another person, you’ve got to work with this guy’.

GC: Yes, to our credit, you’re right, you’re right, they did respect the people’s opinions in the band and they account for a lot in these situations. Because I think if anything, and this applies to any band I think, that they know what they don’t want to sound like, do you know what I mean? They might not know what they want to sound like, but they know what they don’t want to sound like. And so in terms of that, I was trying to kind of flex a muscle there, but you’re right, they did, they did take it onboard and they did respect us and they did think that we were in a madness, that there was a sort of method there. So yeah, fair play to them man.

SDE: So, I have to ask you about the future of Wet Wet Wet. Obviously, Marti has left.

GC: Sure.

SDE: Why did he leave? Was that bubbling under for a while? Have you got any idea of what happened…

GC: Well, I think that’s a question for him really, I think that he’s kind of set his stall out and the fact is, I haven’t spoken to him and I can’t really second-guess where his head’s at.

SDE: Did you play those live shows in the summer? Did they go ahead as planned?

GC: Yes, they did, yeah, that’s the surprising thing, you know. You think you know things and we were going to go out there and play three gigs and it was all going great, I thought, and there was talk of a new album. Marti was here at the beginning of the summer time in my house writing songs with me, so yeah, we have our moments, as we all do, but to do that and sort of step out, I just felt ‘do you know what, I’m a bit disappointed, I’m a bit sad’, but at the same time, I still feel that if he would get off his … if he would fucking stop doing fucking pantomime, then we might have a fucking chance to do something as a band, do you know what I mean. It’s sad and I’m sorry to see him go, but life does go on. I know people will … it’s a difficult kind of perspective to look at, without somebody like Marti in there, but I’m confident that there’s maybe mileage in us yet. And I don’t think it’s time to say ‘let’s hang up the bass and stop’, I think there’s still a little bit to go, and there might be a few twists and turns, you never know.

SDE: But can Wet Wet Wet exist without Marti Pellow, going forward?

GC: I think they can, you know, I think it does. Now, whether it’s to people’s tastes and whether they like that or not, that’s a question I can’t answer, but what I can answer is saying ‘yes, we can and we are’ and that’s a fact, that’s Neil, Tom and I have … we’re waiting for the dust to settle a bit and then we can make a plan and move forward, but you know, look at Genesis, look at Mike and the Mechanics, there’s life after the singer man. So who knows what that life is, but there’s definitely life after the singer.

SDE: It’s just rather unfortunate timing, isn’t it, with this big anniversary and the re-issue and all that. Especially since Marti was obviously involved, to some degree.

GC: Well, this is the whole thing… I can’t really make any sense of it, because it’s not as if this release has been sprung upon anybody, it’s been scheduled in for a long time as well as other things. But listen, first things first, we’re here to talk about that, and listen, I do know we have to speak about that, because it’s like the big fucking elephant farting in the room man. It just seemed that Marti went out on a bit of a limb and said what he said and put it out there and the press jumped on the fact that he’d left the band. And so, aye, I still feel that we’ve still got life, there’s still something to say, musically, and let’s face it, for the last couple of years, Marti has been in more pantomimes than he has been in Wet Wet Wet tours man and as bizarre and banal as that sounds.

It just seemed to me that he wanted to be in a pantomime more than he wanted to be in Wet Wet Wet and so can you compete against that? I kind of think that, without wanting to overshadow the release and the celebration of an album that we made, it’s now come down to a bit of a pantomime, but the fact of the matter is that if he wants to go and do pantos, then that’s up to him man, you know, but I still think that the band has more to offer than a pantomime.

SDE: It doesn’t sound like there was any sitting down, heart-to-heart in a room, it was just like you’ve got the communication that he’s leaving and that’s it.

GC: Yeah, it was that, you nailed it, you nailed it right there, that’s it and that was why I’m … that’s the disappointment really, that nothing was even … there was no consideration for anybody. And it just seems a bit churlish to spit the dummy out and I just don’t understand it, but that’s thing, if nobody communicates then how can you expect to move forward?

Thanks to Graeme Clark, who was talking to Paul Sinclair for SuperDeluxeEdition. The five-disc super deluxe edition of Wet Wet Wet’s debut is out now.

Compare prices and pre-order

Wet Wet Wet

5-disc super deluxe

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Popped In Souled Out / Super Deluxe Edition

Disc 1 – Remastered album with bonus tracks

- Wishing I Was Lucky

- East Of The River

- I Remember

- Angel Eyes (Home And Away)

- Sweet Little Mystery

- I Don’t Believe (Sonny’s Letter)

- Temptation

- I Can Give You Everything

- The Moment You Left Me

- Words Of Wisdom

- Don’t Let Me Be Lonely Tonight

- World In Another

- Wishing I Was Lucky (Live at The Wendy May Show)

Bonus Tracks

- Sweet Little Mystery (Live at Capital Radio)

- HTHDTGT (Live at Capital Radio)

- Angel Eyes (Single version)

- Temptation (Single version)

- Sweet Little Mystery (Single version)

Disc 2 – The Memphis Sessions with bonus tracks

- I Don’t Believe (Sonny’s Lettah)

- Sweet Little Mystery

- East Of The River

- This Time

- Temptation

- I Remember

- For You Are

- Heaven Help Us All

Bonus Tracks

- Piece Of My Heart

- Wishing I Was Lucky

- Home And Away

Disc 3 – B-Sides, Remixes and a Number One

- Wishing I Was Lucky (12” Version)

- Wishing I Was Lucky (Metal Mix)

- Words Of Wisdom (Wishing I Was Lucky B-Side)

- Still Can’t Remember Your Name (Wishing I Was Lucky B-Side)

- Sweet Little Mystery (12” Version)

- Sweet Little Mystery (Mista E Mix)

- May You Never (Live / Wet Pack Track)

- We Can Love (Angel Eyes B-Side)

- Home And Away (Demo Version / Angel Eyes B-Side)

- Heaven Help Us All (Temptation B-Side)

- I Remember (Extended Version / Temptation B-Side)

- Bottled Emotions (Temptation B-Side)

- With A Little Help From My Friends (Single)

Disc 4 – Unreleased and Rarities

- The Moment You Left Me (Planet Studio Session Nov 1984)

- Home And Away (Planet Studio Session Nov 1984)

- East Of The River (Planet Studio Session Nov/Dec 1985)

- Wishing I Was Lucky (Planet Studio Session Nov/Dec 1985)

- I Don’t Believe (Planet Studio Session Nov/Dec 1985)

- Words Of Wisdom (Planet Studio Session Nov/Dec 1985)

- East Of The River (Amazon Studios Sessions Jun 1985)

- Temptation (Amazon Studios Sessions Jun 1985)

- World In Another (Amazon Studios Sessions Jun 1985)

- For You Are (Amazon Studios Sessions Jun 1985)

- I Suppose (Amazon Studios Sessions Jun 1985)

- I Can Give You Everything (The Manor Studio Oct 1985)

- I Can Give You Everything (Comforts Place Sessions Oct 1985)

- We Can Love (Comforts Place Sessions Oct 1985)

- Wishing I Was Lucky (12” Gotta Job Mix)

- Wishing I Was Lucky (Instrumental Dub)

- Sweet Little Mystery (Dub Version)

Disc 5 – DVD: Pop It In The Player! Promo Videos, BBC Performances and Snapshots – The Story of Popped In Souled Out

- Snapshots – The Story of Popped In Souled Out – Band interviews

- Wishing I Was Lucky (Promo Video)

- Sweet Little Mystery (Promo Video)

- Angel Eyes (Promo Video)

- Temptation (Promo Video)

- I Remember (Promo Video)

- With A Little Help From My Friends (Promo Video)

- Wishing I Was Lucky (US Promo Video)

- Full Scale Deflection (BBC May 20th 1986)

- Wishing I Was Lucky (BBC Whistle Test Mar 25th 1987)

- Temptation (BBC Whistle Test Mar 25th 1987)

- Wishing I Was Lucky (BBC Top Of The Pops May 21st 1987)

- Wishing I Was Lucky (BBC Top Of The Pops Jun 5th 1987)

- Sweet Little Mystery (BBC Top Of The Pops 13th Aug 1987)

- Sweet Little Mystery (BBC Top Of The Pops 27th Aug 1987)

- Angel Eyes (BBC Top Of The Pops 31st Dec 1987)

- Temptation (BBC Top Of The Pops 31st Mar 1988)

- With A Little Help From My Friends (BBC Top Of The Pops 12th May 1988)

Interview

Interview

By Paul Sinclair

30