In Conversation with Tony Visconti

“We don’t have enough geniuses making records anymore”

“I thought record producers were horrible people”

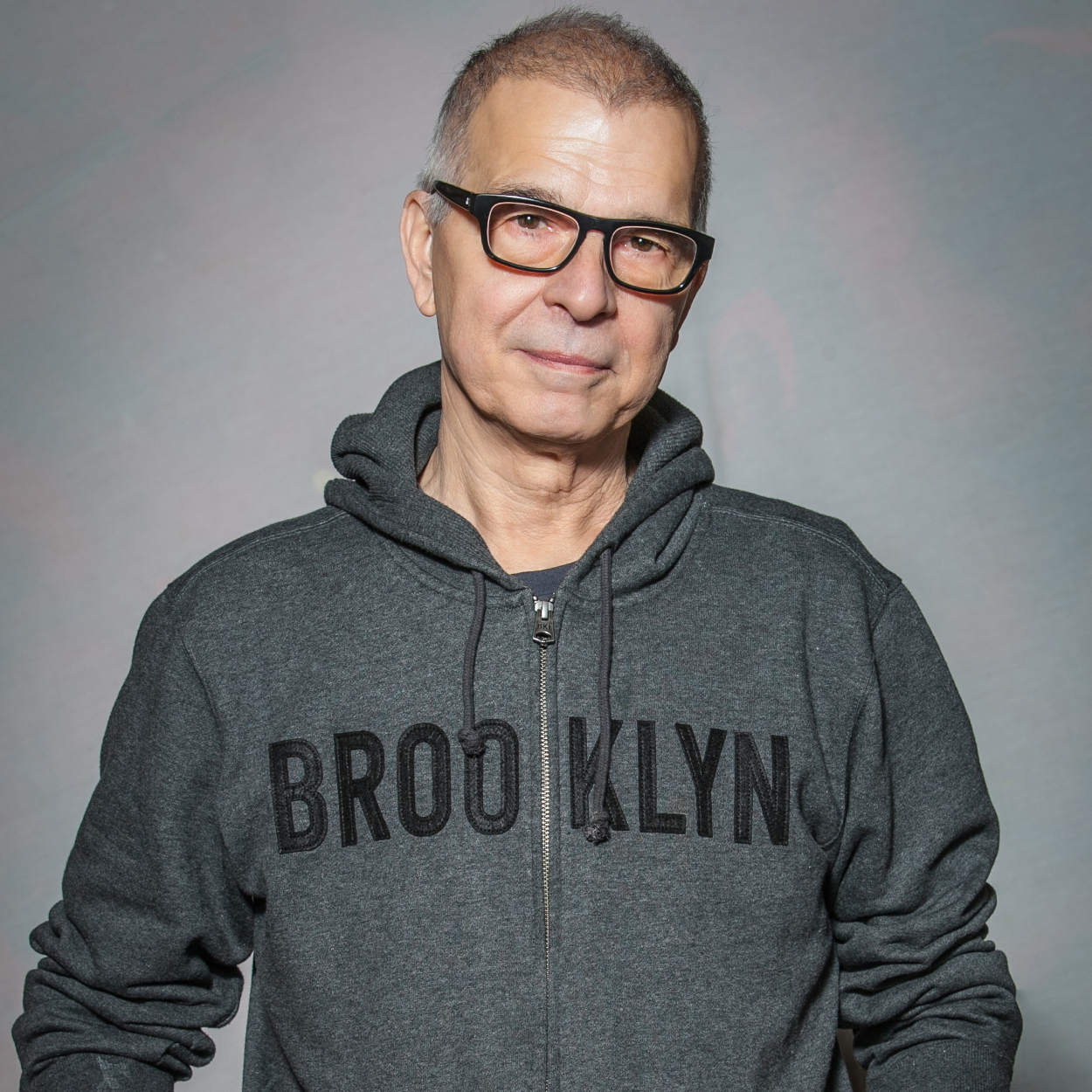

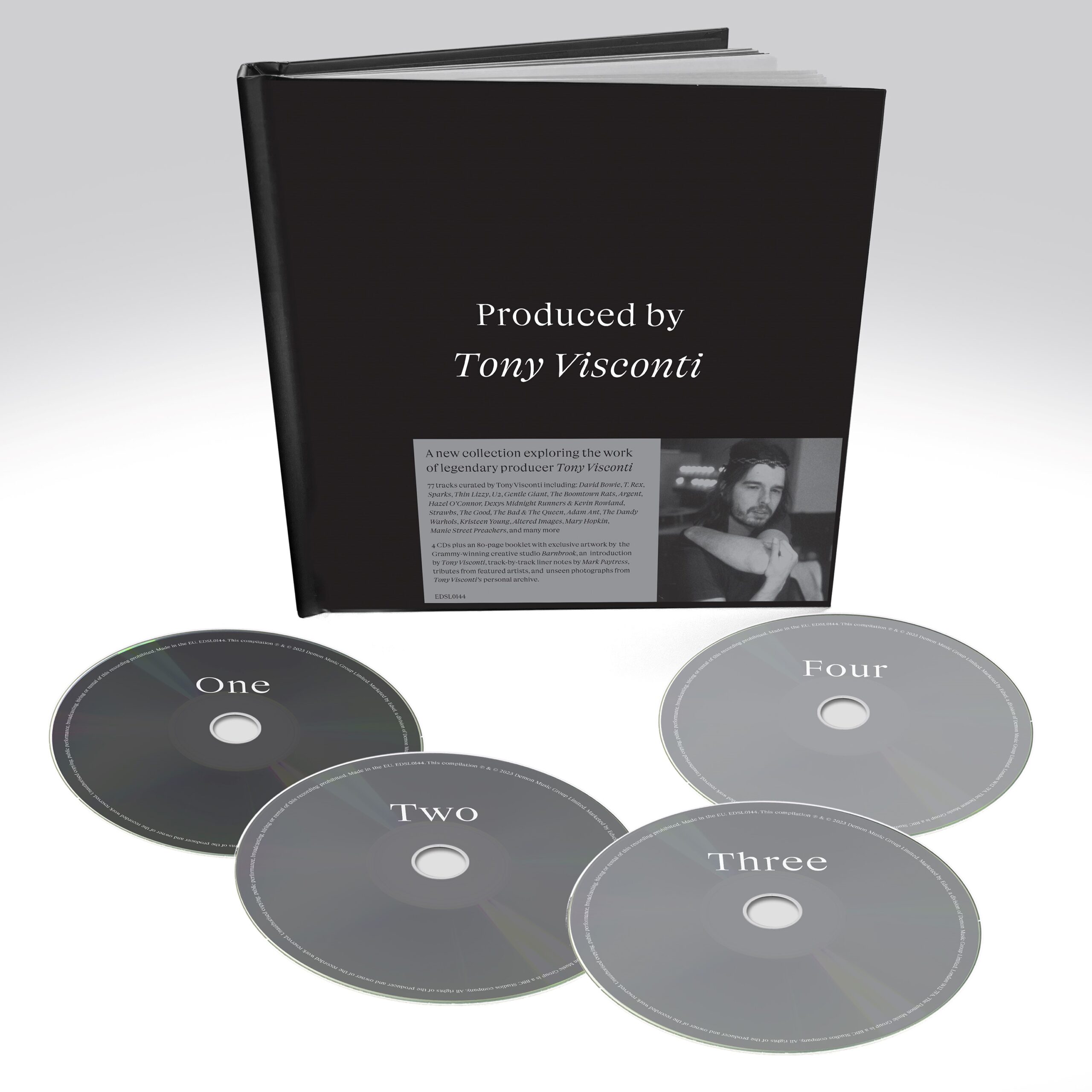

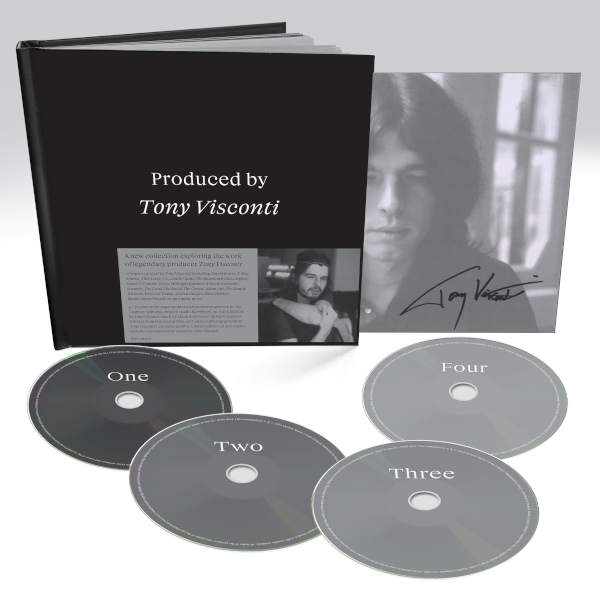

Legendary producer Tony Visconti sits in his New York City studio looking unfeasibly youthful for a man in his late Seventies. He’s Zoomed into talk to SDE about his new box set which spans the producer’s entire working life and features famous material from David Bowie, T.Rex, U2, Joe Cocker and many more…

SDE: We’re here to talk about Produced By Tony Visconti, your new box set. There’s so much music: five and a half decades, with an amazing array of artists and genres, across the decades. Are you pleased with your life’s work?

Tony Visconti: I’m very pleased with my life’s work. I’ve worked over five decades, and I’m still working! The music I produced in every decade was different from the last and then the next one to come. I’m pretty happy that this set is a little overloaded with the 80s. That was a fertile decade for me.

How did you cope in the 80s with all the technology, like the Fairlight and sequencers? Did you enjoy that aspect of it?

Yeah, I realised quite late in the 70s, that if I don’t get into the technology, I’m going to be seen as a dinosaur. So, I got into the technology and I had full blown digital studio. I linked it up with my analogue machines. I went high tech, I had a good technical staff, and I was pleased that I moved into the 80s gracefully.

The role of a producer, within the industry, is quite well understood and established, but to the public at large, maybe it’s a little bit of a mystery. In your own words, could you explain what a producer’s role is, in a studio?

Well, a record producer is somewhat like a film producer. Inasmuch as, I will arrange everything from the beginning; I will hire people, like if I need a musical director. Of course, I’ll need an engineer, I’ll need a studio. So I organise all that. But the other role, the major role, that a record producer plays is he or she is more like a film director. So I roll my sleeves up in the studio and I get involved with the group’s music and their ethic. I want to know what they’re trying to achieve. Unlike a lot of producers who have a ‘sound’, I have no sound. I want to know what the group sound is, and I want to embrace it and embellish it, and make it stick to the wall [laughs]. All those things.

It’s very interesting you mention about not having a sound, because I was going to ask you about that. Jeff Lynne is a good example of a producer who has what you might call a signature sound, for example the drum sounds on the records he producers tend to sound quite similar.

I’ve got two sounds of mine that I’m involved with that are very identifiable, and I would say they are as much as my sound [as the artist’s] .When Marc Bolan and I worked together it was our sound. He could only go so far, technically and musically and I supplied the rest with the strings; the mixing; the engineering; backup vocals – when Flo & Eddie weren’t available, I did backup vocals with Marc – so that’s my that’s my sound. I’m 50% of that sound. With Bowie, whenever I worked with him, the two of us were autonomous; we made decisions together. Sometimes he would override mine or I would override his, so it was very cooperative. And all the Bowie records I produced, from Space Oddity to Heroes and onwards, that’s much very much a collaboration and I have to say, that that’s my sound too. Some other artists I work with, I put maybe a little more of myself into it, if they just have good songs, but no real ideas. I’m never at a loss for ideas! I mean, my brain… I wish I could stop it sometimes, you know, I just keep thinking and thinking. But that’s how I would describe the role: we are, in the sense of films, a producer, we organise it, and then we’re like a film director, we direct the artists.

Musicians and singers are frightened when they get in a studio

Tony Visconti

Film directing is a good analogy. Some people say if you can ‘see’ the direction then it’s getting in the way. In other words, you shouldn’t notice it. Do you feel the same about music production, that maybe people shouldn’t be noticing the production, necessarily?

That’s a kind of a goal. But because they don’t spend as much time in the studio every year as I do, musicians and singers are frightened when they get in a studio, they’re a bit trepidatious; all kinds of things are going on in their heads. And I can see that. They say a producer has to be a psychologist, and I never took a degree in psychology, so I’m not going to say I’m a psychologist, but psychology is obviously a good tool, if I can read what they’re going through. And I try to understand, what a particular pain is, in the whole process and what their strengths are. I like to find the strengths and build them up, give them confidence. And if I have to step in, I’ll suggest a chord change, or a melody change – with permission, I won’t force it on them – you know, “maybe this will sound better?”. And they’ll try it and they say, “good”, or they’ll say “rubbish”. I’m very flexible and I’m very compassionate as a producer.

When you take on a job, do you insist on hearing the songs first? Do you want to understand the quality of the material that you’re going to be working with?

That helps a lot. I would love to hear the scraggiest demos they have, it doesn’t matter. They don’t have to be slick. Although in recent years, people now have studios in their laptop. They send me like these enormous [and sophisticated] demos. And sometimes we just take them and put them into my Pro Tools. And we just build up the demos, because they’re so good. But in the old days, demos were pretty nasty. They were just sung into a cassette player and so you had to build up on something that was very, very basic.

When artists seek you out and try and get you to produce their record, what do you think they’re looking for? Do they just want some of that Bowie/Bolan fairy dust? Or are they after something specific?

Well, having had all these great records with Bolan and Bowie, of course, I get called and it’s like “give us some of the fairy dust”. And as I said just earlier, the Bowie and Bolan sounds are pretty much part of me, as well. That’s my bass playing, sometimes, it’s my string writing, it’s my backing vocals, my ideas. So when they want to get a Bowie or Bolan sound, they’re getting me; I was there, I did that stuff. Not everyone wants that, but the people who do, we can do it. To make a glam-rock track nowadays isn’t a bad thing. People are still going for it. Nowadays, it can sound more like a pastiche, but if it’s a good pastiche, it’s sellable. Fans will appreciate it. You know, I love to go the other way and do something completely opposite. Like I get some singers who are a soloist who are very dramatic. And they need they need everything and they want a big string section. I was very attracted to Elaine Page a few decades ago, because my goal is to work with the greatest singers I could find. They have to be really great if I work with them, because you can do more with a great singer; they’re more flexible. You could suggest things and they’re capable of going out of their comfort zone and trying their best. Elaine Paige was so good to work; with I made four albums with her.

I was going to ask you about that. Yes, four on the trot in the 80s

Yeah, I’m working with a West End musical singer! She wasn’t very tall, but her voice was huge, absolutely huge. And she loved to be directed; she wanted direction. One of the first things she said to me when we started working together was “I don’t suffer fools” and I said “Well, you won’t suffer me, so don’t worry about that!”

Sometimes with a band, where you might have five, six members in the group, you’ve got the baggage of keeping everyone happy, but I guess it simplifies things when you’ve just got one vocalist?

Yeah. When you have a five-piece band, you’ve got five producers as well, and you can see what happens when that happens with the infamous ‘Troggs Tapes’ when it just goes south, from almost the first minute for the next half hour!

Tony, you’re a very accomplished musician, yourself. You can score and arrange strings and all that kind of stuff, which is an amazing talent on its own. How important has that been for you? Do producers need to be musicians or understand music themselves?

Well, in my case, I am musically trained, and I learned to write scores before I left high school. So I was writing scores at 16 years old. And I was taken under the wing of the head of the music department, a lovely man called Dr. Silberman. And he gave me private lessons as well; my parents couldn’t afford to send me to a university. So this was it. Shortly after I left high school, I was writing arrangements for people, always remembering the lessons of voicings that Dr. Silberman taught me. My idol is this day is Beethoven but also George Martin. Beethoven was a very accomplished musician, but he was never was in a recording studio, but George Martin used all of his musical training, and it didn’t hurt, to have that kind of a background. I don’t have to impose that upon people, but when I’m called upon to help them with their backing vocals, that comes from my musical training background, I know a lot about this stuff, without coming down heavy on them, you know. And a lot of people know that I have this and they want it. So it depends. I’m flexible.

There’s a couple of tracks from Badfinger, although they were called The Iveys for the first number, ‘Maybe Tomorrow’. That’s a lovely song, one which I’m amazed wasn’t a bigger hit at the time. You were in the middle of that 1968/Apple Music/Beatles vibe. You were there when that was happening, which must have been extremely interesting.

It was fabulous. I went into Apple, they had an open-door policy for a while, and you had Hells Angels walking in and all kinds of people. One day, I walked in to speak to one of the Directors [of Apple], it was maybe about The Iveys, and the door opens and George Harrison casually walked in, sat in another chair, and he just crossed his arms and he listened, you know, and I just thought “Wow, that’s George Harrison!” [laughs]. But if you walked around Apple, you’d eventually see every Beatle. 3 Saville Row, I’ll never forget the address, it was such a cool way of doing business and being so open about it. It backfired though and they eventually had to put a lock on the door, but it was a great time.

Paul McCartney gave ‘Come and Get It’ to Badfinger, and he was a mentor for them for a little while, wasn’t he, but it occurred to me that when he got you to work on the orchestration for Band on the Run a few years later, that was because he would have known about you through this period. He must have been aware of your skills and what you could do.

Partially. He was aware of that, but he double-checked by phoning me. He was a T. Rex fan and he said “Those string arrangements, they’re really good. Who wrote them?” I said, “I wrote them”. He then asked if I could read and write music and I said “Well, yes, I can. Because I wrote them!”. And he goes, “Okay, well, I’ve got this little project and maybe you could come over to me”. So I went to his house a few days later, in St. John’s Wood, and then we started together working on those arrangements, for Band on the Run.

George Martin got a little upset when I was doing those ‘Band on the Run’ orchestral arrangements

Tony Visconti

But would you ever pitch for a job, Tony? Or do you just think, “if they want me they’ll ask”? Because I was thinking about that with Band on the Run, because Paul had got back from Lagos, and he had all these tapes and recordings and you could easily have taken a bit more of a production role on that record. I know Paul’s an accomplished producer himself, but was that something you thought of suggesting or hinted at?

It was in the air. We talked about it. He was definitely trying to be known as a producer. His first experiment was ‘Those Were The Days’, with Mary Hopkin. And he did very well. That’s an incredible production; it’s really great. So I don’t think there was enough space for me in his productions to be a co-producer, or anything like that. He saw me as an arranger, which was good, because I really enjoy that role as well. I know, George Martin got a little upset when I was doing those arrangements. He assumed that he was always going to write arrangements for the Beatles. Even when they were solo.

That’s interesting. He would have orchestrated Live and Let Die before that.

When George and I finally met, we got on. We had a great lunch at some recording studio in North London. I had a few meetings with him, and he was charming. He was really a great guy.

What about the commercial aspect of producing? In the heydays of the 70s, and the 80s, were you thinking about how many millions the album might sell and how much money you might make? When he worked with Madonna, Nile Rodgers ended up making a lot of money, because he brokered a great deal. Everyone needs to make a living and everyone enjoys seeing their songs go to the top of the charts. How much does that influence you?

Well, you know, I see it is an art first. But secondly, it’s always been my business since I was about 17 years old. When I started, I played a wedding and I got paid. I liked playing music, and somebody’s paying me for playing music. When I went into the recording business, obviously, you read the newspapers, and you see that if you sell a million records, and you have a percentage of that, that’s a big windfall. So I was attracted to that part as well because it creates a sustainable career in life. For me, I’m able to have a family – or two; I’ve had two families – and so the commercial aspect is important. But I’m a bit of a snob, so it needs to be on my terms. I can’t I can’t copy the style [of someone/something else]. A lot of labels will look at the top five in the charts and they’ll ask you to produce something like those top five – I can’t do that. So, my experience is that records that come out that sound very unique, something you haven’t heard before, they also sell well. And in my case, you know, T Rex and Bowie and a few other people I’ve worked with, we’ve come out with some pretty wild sounds and they’ve gone to the top of the charts too.

Talking of David Bowie, I think there’s four selections on CD boxset but none on the vinyl which I understand is down to licensing issues.

Yes.

The four songs you have included are ‘Young Americans’, ‘Memory of a Free Festival’, ‘The Man Who Sold The World’ and ‘I Would Be Your Slave’. What informed that selection, because there were many great songs to choose from and there’s nothing from the so-called Berlin Trilogy?

I worked very closely with Demon Records, they made a lot of selections, which they put to me. I looked at the list and they said you can take anything off or put anything on. The problem is my memory is pretty selective these days, I can’t remember everything I’ve recorded. Someone said to me, the other day, “You left [British Afro Rock band] Osibisa off the box set”. Quite honestly, I forgot that I recorded them! [laughs]. I didn’t remember. I mean, I think my manager has a list of my recording history, but I was so busy during this period, I just was very happy that they made the selections. And then I took some off and I added quite a few, as well.

You had such an amazing experience working with David Bowie in the 70s. And then later on, of course. In the early 1980s, he moved on to work with Nile Rodgers on the Let’s Dance album, of course. I’ve read that you were you were a little bit upset at the time, but do you think that was the right decision? Or do you still think he made a mistake and you should have produced that album?

No, I think I think he made the right decision because he told me that he wanted that elusive number one hit American hit [‘Fame’ did actually get to #1 in the USA, of course]. So David wanted Nile for that. And it was so good that I spoke to David and I said, “Well, I guess we’re not going to work together anymore. But good luck. Congratulations. Let’s Dance is a big hit”. I personally never liked it. It’s just not David Bowie.

It was interesting, because whatever you think of that record, it turned him in a slightly different direction for the next half a decade or so, which is probably the more important fact about Let’s Dance. He seemed to go off course, a little bit, by his own standards anyway.

Some of the tracks, I love. I love ‘Modern Love’. That was a good track. It wasn’t a bad album in any way; he just did something different. We didn’t always work together, which was a good thing. Because over my career, I’d do a few albums with other people, a David Bowie album, then I go and work with other people. So he had every right to work with other producers. What happened, when we came together again, was that we’d learned more stuff from the people we’ve worked with. I haven’t counted, but I’m sure I produced over 20 David Bowie albums, when you put the live albums together and the reissues and bonus tracks. I’m pleased… I mean, I produced one of his first and certainly his last, his last four in fact, in this very room [Tony is in his Manhattan studio], I’m sitting in, we did the finishing off of those last four albums.

Joe Cocker’s version of ‘With A Little Help From My Friends’ is on this collection, and that’s obviously an amazing track. What was your involvement with that particular song?

Well, for my first year in London, I was Denny Cordell’s apprentice, and assistant. I didn’t really know how to produce records, until I worked with him. He didn’t know how to arrange things [although] he was a good vocal coach, a good band coach and he was charming. He had a lot of charm. The first strings I wrote for him was for The Move. And then with Joe Cocker, he wanted some brass and some help with the backing vocals. And so, I was always at his side. I’m an Assistant Producer on that track, although I’m not credited and I wrote brass for the entire song, but he wanted the brass only to come in during the fade out. Also, I mixed that record which I’m not credited for.

I was in the Top of the Pops studio audience in 1984 when Adam Ant performed ‘Apollo 9’. That was quite exciting for me, but what was it like for you to work with him on that record and the album?

It was great. I had a lot of people tell me that so and so is a problem. They told me Elaine Paige was a problem, and we got on like a house on fire. [They told me] Adam Ant was a problem, and we got on like a house on fire. He was a charming man to work with. He was smart, I could see immediately he was smart and very focused. He was very, very sharp. And was also okay with me making suggestions and changing things around a little bit. I got his confidence very early on. But there was nothing difficult about him. As far as I was concerned, I listened to him, he listened to me. And we had mutual respect for each other.

That’s a very 80s sounding record. When you’re working on those kinds of productions, was there ever a little bit of you thinking, “I prefer the classic sound of 60s or 70s rock”?

No, I always move on. I know that there are certain qualities of 60s and 70s rock that you could always use, cautiously. But you don’t want to imitate it, you don’t want to recreate the decade, it’s gone. I wanted to be an 80s record producer, definitely. I didn’t want to be seen as a dinosaur. And I learnt the technology, the language. And one thing that was really on my side, I was very prolific in the 80s because my studio in Dean Street was almost a closed shop. I was recording so many people as a producer, we almost never had any time to sell to other producers. So in that decade, you see people like Altered Images and Hazi Fantayzee coming walking in through the doors… My studio was like a Hit Factory, it was fantastic to have that facility, and not having to worry about booking studio time – it was my studio.

Where did that work ethic come from? It is a crazy amount of artists that you’ve worked with and albums you’ve produced over the decades. What instilled that work ethic in you?

What’s that expression, “Make hay while the sun shines”? It was it was a very good decade for me and I already had a good track record. I was attracting younger people to come to work with me and I think it was vital that I work with younger people. And also, the crossover band was Thin Lizzy from the late 70s to the early 80s. I was I was working with them and I always loved them and I thought I wouldn’t be a good match for them, but I made three decent albums with them that charted and did well for them too.

Morrissey said, “I only want you to tell me two things, whether I should sing louder or quieter”

Tony Visconti

Like Adam Ant, Morrissey is another one of those characters whose reputation precedes them a little bit, but you seemed to work quite harmoniously with him. Unfortunately, there’s nothing from the album [2006’s Ringleader of the Tormentors] on this collection, but how was your experience with Morrissey?

I don’t know why we didn’t get a Morrissey track. It could be that the licence holder said no. Or maybe he’s got plans to release a ‘best of’ Morrissey. I could see that. But again, people said that he’s difficult and to work with and all that, and I remember the first day I went into the studio with him and I went in cold. I didn’t have any pre-production. He’d had a producer already on that album, whom he sacked. And so, I inherited the backing tracks; we didn’t cut new tracks. And I started out with overdubbing guitars and building up the production and he was very bemused by it. He wouldn’t say much; he would sit in a studio and ponder everything that was going down, and he was just thinking very strongly about things. If he had something to say he’d say it in a very nice, soft spoken voice, but he never opposed me on anything. And the funniest time was when we came to doing the lead vocals. We waited until the very end, most of the band is left and he’s front of a microphone, and he said, “Now I only want you to tell me two things, whether I should sing louder or quieter”. He didn’t want to be coached. So by take one, or two, or three, I just said, “I think you could do another one, for me” and he said, “Why?” And I said something like, “Maybe you could give me one with little more energy, just to give me an alternative. So if I do a composite of your voice, I’ll have a few options. You never know, you might, sing a gem, something that’s really great that you haven’t done already”. And when I put it to him like that way, he was agreeable. I think a lot of producers really don’t know how to talk to artists, and he must have had a bad experience. The reason why I think I communicate well, with artists, including the most difficult ones, is because I had a musical career. And I thought record producers were horrible people. I was spoken to in the rudest manner, by some record producers, when I was sitting there playing guitar and singing and stuff like that, back in New York. And I vowed never ever to treat it artists like that. I think that’s why I’ve got a lot of respect from the people I’ve worked with. And there are testimonies in this box that book from people I work with. They’re confirming that I’m a cool guy to work with [laughs].

There’s that story about Nigel Godrich, when he worked with Paul McCartney [on 2005’s Chaos and Creation in the Backyard”] and he put Macca’s nose out of joint a little bit, by saying “this song isn’t good enough”, or something like that. I’m guessing that isn’t the way you work?

Oh, I have rejected songs. Without naming names, I worked with a very big group, and I would say “this song could be better. And instead of recording it right now, could you go home and consider a rewrite some of the lyrics” and the artist took it very well, and the group took it very well. We ended up making a couple of hit records together. Depends how you frame it. You know, you can’t be an [adopts English accent] an arsehole.

Are there any people that got away? Any artists you’d love to have worked with? People that you haven’t ticked off the list?

Well, I was I was lucky enough to meet every Beatle and work with [some] of them in one form or another. I would have loved to have worked with John Lennon. And I think had he lived, that time would have come. I mean, he and Paul were the two favourite Beatles but all of The Beatles had a unique quality – that’s what made them a unique group. It was like four lead singers, four lead musicians, and all that. McCartney… it would be nice to work with him. He’s still around. I might still work with him again, you never know.

You did work with Paul in the 1980s of course, at least a little bit. You orchestrated the single mix of ‘Only Love Remains’, from Press to Play.

Yeah. And I’ve met Paul socially, since then. Mick Jagger threw a big party at his Chelsea home and I had this funny conversation with Paul where he’d come up to me and we talked face-to-face about music and about our families and everything. Then he starts adjusting my lapels on my suit jacket, and then he starts adjusting my tie and he’s dressing me! [laughs]. I found this bizarre, except I know there’s this thing called neuro-linguistic programming which I studied and it’s when you touch people, and tap them and you’re actually putting a slight hypnotic control over them. So I thought, maybe he studied that, he’s very erudite. Maybe this technique works for him. But I knew what he was doing. And I found that a little funny, you know. Awkward, but a little funny. He’s an amazing guy. A friggin’ genius. I love him.

Because it’s to do with production – although it’s not on this collection – I wanted to ask you about working with the Finn brothers, about 18 years ago, for their second album, which [Tony’s version] ultimately didn’t get released. They ended up working with Mitchell Froom and did some more recordings. There’s a song called ‘Luckiest Man Alive’, and your version of that song did appear on a special edition, so fans can actually compare two producers’ work on the same track, which is fascinating and not something they would normally be able to do. This is a long-winded way of saying, what happened with that album? Have you got thick skin? Can you just shrug it off and go, “Oh, well, they wanted someone else”?

Well, you know, I put a lot of myself into that record, I worked very hard making it. And we originally worked with musicians they brought from New Zealand, to play with them. They were okay… It was hard work with them, but you know, they wanted like their ‘music brothers’ with them. But when I was finished with it, it was a quite an organic album. It sounded like a band in a studio, there were overdubs and I liked it very much. But all along, I think Neil… he wanted a real artificial [sounding] record, you know, something like bigger than life very, very controlled. Everything tuned and fixed and tempos fixed and everything like that. So he went on to record with someone else [Mitchell Froom] and it’s not the first time that happened to me, that a record was taken away. A Difford & Tilbrook album was one that was also taken from me. One day I wake up, and they just say, “Don’t bother coming to the studio, we’re going to finish the album with someone else”. Thanks a lot!

It must be hard not to take that personally, because you put all the energy into the record.

Of course, I was hurt. You know, I got feelings.

What do you think has happened in the industry to the role of the record producer today? And is it even a sustainable career for an up and coming aspirational producer in the way that it used to be?

Well, over the years, the role of a record producer has been modified, changed a lot. There were record producers in the 50s and they weren’t even called record producers. It would just be someone in charge of the record. In my generation, the 70s was such a golden decade, because people were making real records and real studios, with great musicians and we didn’t have auto-tune, and the only way you got into the recording studio is by being great. Record labels signed people who were great, they didn’t sign a cute looking person and then fix the voice, fix the image, Photoshop the photos, which came later. With the record industry now, they almost bypass producers completely and go with some young person who is a whiz on the laptop and make their own stuff. They make their own videos. And I think that’s very admirable, but it has less dimensions in it then the organic music does. When you hear it once, you hear it all; the second hearing of modern music you don’t hear anything different or anything new. It’s everything’s repeated, everything is fixed to death. There is no idiosyncrasy in the vocals anymore, unless they do auto-tune on purpose, in the way that Cher made famous.

The 70s was a golden decade. Record labels signed people who were great, they didn’t sign a cute looking person and then fix the voice, fix the image, Photoshop the photos

Tony Visconti

People are still making organic music, and I’m involved in a couple of groups that are doing that, but labels are frightened of that and the labels never had courage. Never ever, in a million years, did labels have courage to break new ground; it happened in spite of them. You get someone like Marc Bolan coming up, or a Bowie. The times now aren’t right for a new Bowie to come out. He would be too radical. You wouldn’t sound like the top 10. And why should he? Why should anyone sound like the top 10? We’ve got enough of those people. But we don’t have enough geniuses making records anymore, I’ll tell you that much.

Is this a cycle that we will eventually spin out of, or are we going to be stuck in it for a long time?

Well, it’s a good question. I can’t predict the future. But I know that the fans, people who buy records, have a low threshold of boredom, they want to hear something new, but that’s not the philosophy of the record labels. There are some labels who are very progressive, and they do sign new people, and they do take a chance. One of the big problems is you have managers and agents who want to get millions of dollars for a signing, they want to get that out of the label. That’s destroyed the business. My advance for making a T Rex album was like £50. But when the royalties kicked in, I made a lot of money from the royalties. You know, some of these deals where a person gets $100m, for making a record, they’re not going to get any royalties from that. That’s it. They’re going to owe the label for like, the next 50 years! [laughs]. That’s a bad business model. If you ran a bank, or any other business, like they were running record labels, it wouldn’t be considered a good business model. It’s not a good business model. So hopefully, there’s going to be some less overburdened record labels, smaller labels, making more money. I think that’s the future of the record business.

But would you encourage someone to want to learn the trade? Engineering and production? Or does that pathway not exist in the same way it did before?

Oh, they still need producers. Everyone’s still needs engineers. Studios in New York are thriving, and I think they are in London, the ones that survived. There are a lot of very skilled engineers who know how to work analogue equipment. People think if it’s analogue, it’s gonna sound wonderful. But it’s the talent on the analogue that sounds wonderful. You still need talent, you need good chops, you need to sing well, play well. But people find out the hard way. Of the 50,000 records that are released a year, only about two percent become hit records, that’s the hard cold fact.

I get the feeling you’re not hanging up your hat, just yet? You’re still busy working and looking forward to the next project?

I’m currently working on two albums. There’s a couple of ones that are coming up in December. And I’m also working in my band, Holy, Holy. We now call it ‘Tony Visconti’s Best of Bowie’ because Woody Woodmansey left the band. Holy Holy was his name. I’m gonna keep working ‘til I drop. I love what I do. Why would I quit this job?

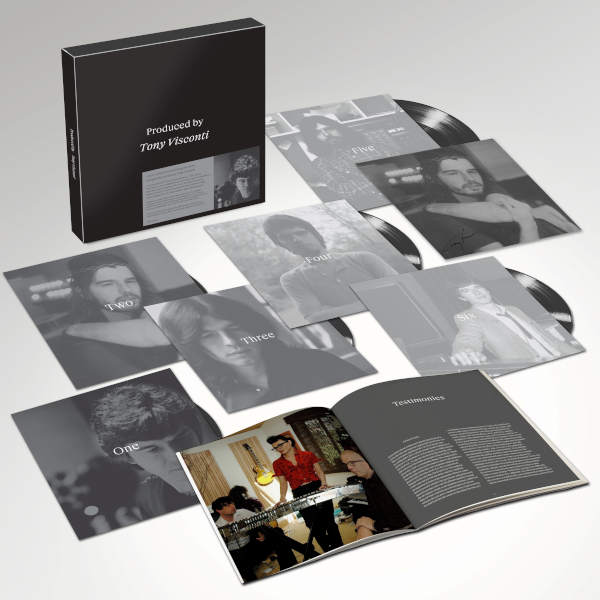

Thanks to Tony Visconti who was talking to Paul Sinclair for SDE. The Produced by Tony Visconti box set is released on CD and vinyl on Friday 20 October 2023.

Compare prices and pre-order

Various Artists

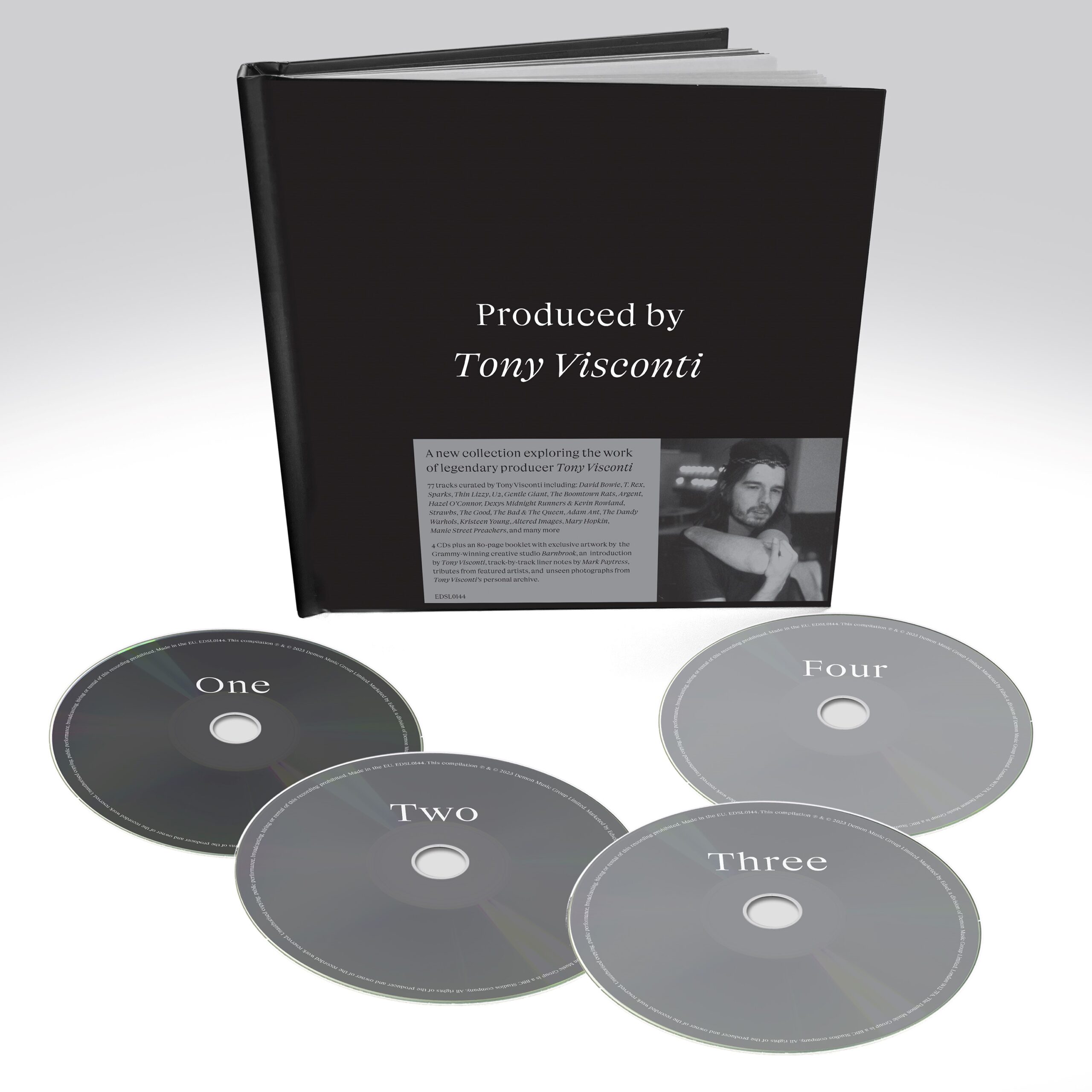

Produced by Tony Visconti - 4CD set

Compare prices and pre-order

Various Artists

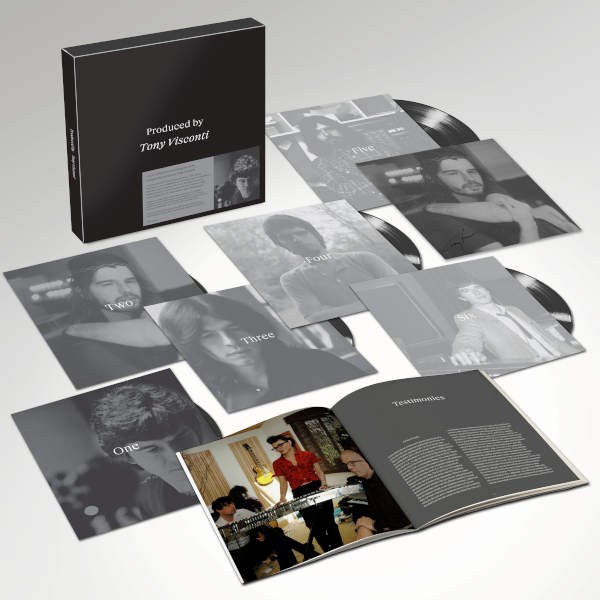

Produced by Tony Visconti - 6LP signed vinyl box

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Compare prices and pre-order

Various Artists

Produced by Tony Visconti - 2LP vinyl

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tracklisting

Produced by Tony Visconti Various Artists /

-

-

CD 1

- Marc Bolan & T. Rex -Teenage Dream [2012 Tony Visconti Master]

- David Bowie -Young Americans [2016 Remaster]

- The Dandy Warhols – Hit Rock Bottom

- Carmen – Bulerias

- Altered Images -Bring Me Closer

- Les Rita Mitsouko – Andy

- Gay Dad -To Earth With Love

- The Dwellers -New Fashion Show

- The Tickle -Subway (Smokey Pokey World)

- Strawbs -Forever

- The Move -Mist On A Monday Morning

- Procol Harum – Magdalene, My Regal Zonophone

- Biddu – Daughter Of Love

- Joe Cocker – With A Little Help From My Friends

- The Surprise Sisters -La Booga Rooga

- The Photos -Life In A Day

- The Alarm -Sold Me Down The River

- Tony Visconti And The Hype – Clorissa

- Perry Farrell & Kind Heaven Orchestra – Pirate Punk Politician

- Kristeen Young – Pearl Of A Girl

-

CD 2

- David Bowie -The Man Who Sold The World [2020 Mix]

- The Seahorses – Blinded By The Sun

- The Damned – Standing On The Edge Of Tomorrow

- Luscious Jackson – Fantastic Fabulous

- T. Rex – Children Of The Revolution [2012 Tony Visconti Master]

- Sparks – Under The Table With Her

- Marc Lavoine – On N’IraJamais À Venise

- Gentle Giant – Nothing At All

- Difford & Tilbrook – The Apple Tree

- The Boomtown Rats – Fall Down

- The Good, The Bad & The Queen – Lady Boston

- Ralph McTell – First Song

- Tom Paxton – The Last Thing On My Mind

- Tucker Zimmerman – Bird Lives

- Tyrannosaurus Rex – Debora

- Tony Visconti And The Hype – Skinny Rose

- Mary Hopkin – Wrap Me In Your Arms

- The Move -Something

- Badfinger – Dear Angie

- Tony Visconti – I Remember Brooklyn

- Modern Romance – Best Years Of Our Lives

-

CD 3

- Stephen Emmer [feat. Glenn Gregory] – Untouchable

- David Bowie – I Would Be Your Slave

- U2 – A Sort Of Homecoming [Live]

- Kashmir – Kalifornia

- Manic Street Preachers – Cardiff Afterlife

- Gentle Giant – Pantagruel’s Nativity

- Mary Hopkin – Streets Of London

- Ralph McTell – Take It Easy

- Tyrannosaurus Rex – Cat Black (The Wizard’s Hat)

- Annie Haslam’s Renaissance – Blessing In Disguise

- The Moody Blues – Your Wildest Dreams

- Rick Wakeman- March Of The Gladiators

- Jon Anderson – All God’s Children

- Zaine Griff – Ashes And Diamonds

- Elaine Paige – Be On Your Own

- Richard Barone – Yet Another Midnight

- Kaiser Chiefs – Little Shocks

- Dexys Midnight Runners & Kevin Rowland – Show Me

-

CD 4

- David Bowie – Memory Of A Free Festival [2019 Mix]

- The Iveys – Maybe Tomorrow

- Junior’s Eyes – Black Snake

- T. Rex – Hot Love

- The Polecats – Marie Celeste

- Adam Ant – Apollo 9

- Phillip Boa & The Voodooclub – Container Love

- Thin Lizzy – Dancing In The Moonlight (It’s Caught Me In Its Spotlight)

- Electric Angels – Rattlesnake Kisses

- Anti-Flag -The Bright Lights Of America

- HaysiFantayzee – John Wayne Is Big Leggy

- Hey! Elastica – Eat Your Heart Out

- The Radiators – Song Of The Faithful Departed

- The Moody Blues -Deep

- John Hiatt – My Edge Of The Razor

- Hazel O’Connor – Will You?

- Strawbs -Witchwood

- Argent -Time

-

CD 1

Interview

Interview

By Paul Sinclair

39