Mod-Curious: Eddie Piller on Mods and British Mod Sounds of the 60s

Modern life isn’t rubbish suggests the Acid Jazz founder

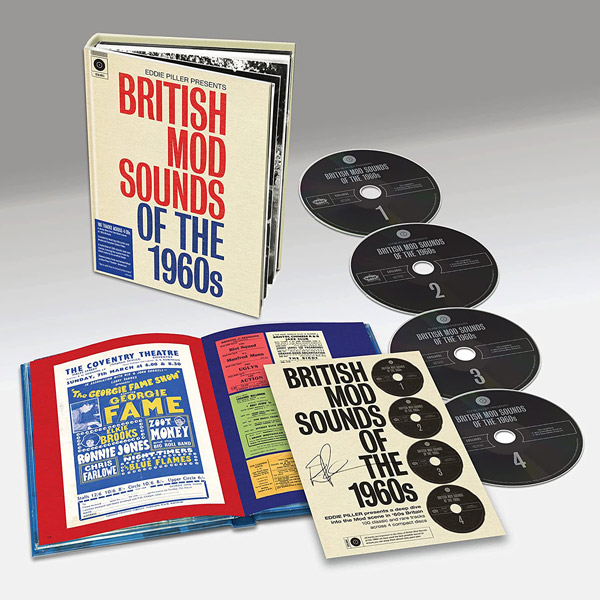

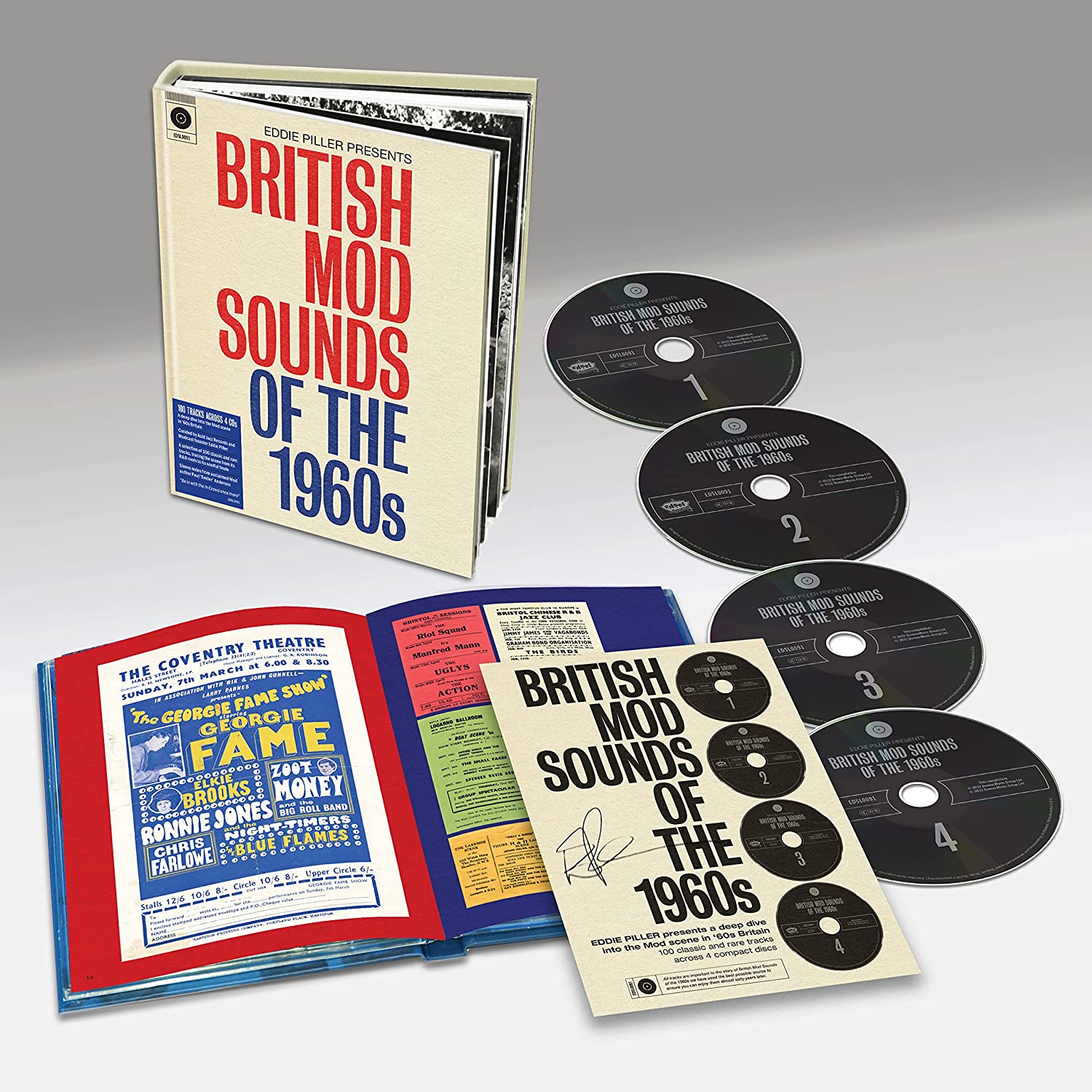

Acid Jazz founder, Eddie Piller, has curated a new 100-track, 4CD deluxe set called British Mod Sounds of the 60s. Released last Friday this set offers a deep dive into the Mod scene in ’60s Britain and includes a selection of classic and rare tracks, tracing the scene from its R&B roots to a soulful finale.

SDE recently caught up with Eddie in a pub in East London to discuss the new release and to try and gain an insight into the Mod scene and mod culture.

SDE: I was born in like, 1969, so I was getting into music in the early 80s – the tail end of the Mod revival. To be honest, I didn’t really know that something else happened previously, for ages – in other words the proper ’60s Mod movement. The very fact that there was a revival, relatively quickly after the original scene happened is quite interesting.

Eddie Piller: Within 10 years…

Exactly. And it’s the usual thing with a new generation of bands, whoever they’re influenced by, as a fan you end up looking back and getting into music from an earlier era. I guess that’s what happened with you, or maybe not because of your mum’s connection to the Small Faces? [Eddie’s mum ran the Small Faces fan club].

No, our inspiration was Buzzcocks, The Jam, Generation X. And what made us wear Parkas… we liked punk music, but didn’t want to be punks. I didn’t even know my mum did the Small Faces fan club until after I turned up wearing a Parka and my dad said, “Why are you wearing that stupid coat?”. And it took The Buzzcocks and The Jam to get me into being a Mod. And the only reason was, I didn’t like punk kids. By 1979 they had become a cliché with the Kings Road tourists, Sid Vicious jackets and haircuts. I was younger than the average punk, but wanted to be different. And my whole generation picked on the Parka, as a piece of iconography, purely to say, “We’re not them”. Because the music is the same. If you listen to The Chords and The Undertones, they’re kind of the same. But The Chords were Mod and The Undertones were punks. So that’s basically how and why it started from my perspective, in the early days, of early 79.

And for those bands you were getting into, like anyone who is serious about music, you read interviews with them, they talk about the groups that inspired them and that’s how you joined the dots and made the connection

You’ve just summed up in that one phrase “joined the dots”. It’s absolutely what happened. We didn’t know anything about being a Mod – nothing. Nothing until so we tried to find out and it was hard in those days. There are a few sociological books by people like Stanley Coen, there was the Quadrophenia album with the photos in the middle, the ’73 issue with the picture book of the Mod kids with the target, but there was very little to tell us what to go on. And the one thing we weren’t was like original Mods – were were just like punks in Parkas. That’s what we got called.

We were just like punks in Parkas. That’s what we got called.

Eddie Piller

So what would be the difference be between being an original Mod and whatever you were? I think of a lot of people understand the fashion and the look and the style more than they understand the music, because Mod music probably doesn’t exist, it’s the music that Mods liked.

Yes, I say that in the in the prelude to the sleeve notes of the box set because you can’t describe Mod music because you have so many different types. You have real Mods in bands, like Small Faces, The Action and Fleur De Lys; you have session musicians in bands that make Mod music; you’ve got black guys in bands that make soul music… I mean, the only real definition of Mod came from The Who’s first proto-manager, Peter Meaden, which was that Mod living, or Modism, is an aphorism for clean living under difficult circumstances. He’s basically the only person who’s ever managed to explain what Mod is, other than Paul Weller. And Paul Weller’s not very clear on it, to be honest!

What does he mean by that?

We don’t know. It means nothing, but it means everything! We don’t know. Clean living under difficult circumstances. Who knows what that means?

To me, it sounds like if you haven’t necessarily got a lot of money but you can still turn out well on a Saturday night…

In the early period of The Who Pete Townshend talks about Mods. Dressing smart like a bank manager… and that’s basically what he got from Meaden. Townshend was very eloquent about Mods at the beginning, but he turned his back on Mods quite early. So you know, we didn’t find out any of this shit out until afterwards; we were just kids who identified with other kids who dressed the same as us, whether it was at football or at gigs. And then, when we realised that at gigs, we could go and see kids that look like us, that’s what we did. [Mod revival group] The Purple Hearts are a good example. Purple Hearts were a year older than me, and I was 15 the first time I saw them in the West End. It’s very difficult for a group that are 16 or 17 years old to be patronising to their audience. And they weren’t. We just felt like they were us, and we were them. It’s a bizarre thing that will never happen again, because music is created by people like Simon Cowell. The main thing to remember about Mods is that it was a reaction to the over creation of punk by the likes of Bernie Rhodes and McLaren – there were no Svengalis in the Mod world, these were kids 15, 16, 17, setting bands up. And by June 1979 there were 100 bands that went around saying we’re a Mod band. They might not know have know what Mods were, but they knew what they weren’t. And what they weren’t, was punk.

We just felt like they were us and we were them

Eddie Piller on Mod revival group Purple Hearts

When did the word ‘Mod’ start getting bandied around then? Was that in the late ’50s?

I’ve written a few books on the subject, and the first time I could discover Mod used in the press, was in The Daily Sketch [British tabloid that ended in 1971] in a music feature about The Flamingo Club where the journalist went to see a jazz group. At that time, in Soho, you had two kinds of people involved in jazz: you had ‘trads’, and ‘moderns’. Moderns got shortened to Mods because that was modern jazz and trads were into traditional Jazz from New Orleans, you know, Acker Bilk with that hat… Mods had Tubby Hayes, Pete King and Ronnie Scott, you know, so the, the split between the two types of jazz, with the kids playing in Soho, first came around in late ’57, early ’58. And so these kids that were modernists – because they’re like modern jazz – gradually became mods, and because mods were always changing, after modern jazz came, the British blues boom, with Alexis Korner and Cyril Davies and all these sorts of people. The next wave of Mod was them playing blues, and then from there you had Rhythm & Blues, with offshoots like Merseybeat, Brumbeat and all that kind of stuff. And then you had soul music. And that was the thing that we defined ourselves by: soul music. And the first exponent of soul music in Britain was probably Georgie Fame. Possibly. Certainly, the first exponent of Ska. Georgie Fame took West African musicians, West Indian musicians and married them to the best of the British brass sections and soul musicians and created probably the archetypal Mod sound.

Yeah, it’s interesting, but quite confusing because there’s so many different strands of music in one thing. When you think about other movements, you know, Punk, Shoegaze, whatever, it’s it’s very much one thing but I guess that’s what the new box set is about – highlighting the different strands?

Mod music is really whatever you want it to be. And no one will ever agree. It could be British Ska, it could be Jamaican Ska, it could be R&B, it could be Freakbeat, but it could be Psych could be Soul. It’s because the music wasn’t fundamental. The philosophy and the attitude was fundamental. The one thing that went through the middle of all of it was the concept of moving forward, attention to detail, clothes, music… Things like scooters, Italian suits, all that stuff, they were kind of periphery things that defined Mods, but they weren’t what Mod was about. The most famous iconography of Mods is the Parka. The Parka was there to protect your clothes. But we didn’t know that in 1979. We just saw all these pictures of kids wearing Parkas and we just though we must wear Parkas. We didn’t have suits underneath them.

Was there as much of a movement originally, compared to when the revival happened?

Yes. In the 60s, it was new. There’s a very interesting quote from Pete Townshend, when he’s on the stage doing Quadrophenia for the first time in America and he said, “Mods to you was probably just Swinging London and Carnaby Street, but to us it was so much more”. And you understand what he means because in America, there was Mods, but it wasn’t the way of life where the bank clerk would dress better than the bank manager and take pills and go to Brighton and start smashing things up. In America, it was about Swinging London and Carnaby Street – it’s a very different thing. And the reason being, it was a working class reaction against the status quo, which was enabled by the American concept of the teenager, which first came around in the mid ’50s, in America, and was an import over here, which led to Teddy Boys, Rockers, Trads and then Mods. And because Mod was always adapting – whereas the others were so stuck with a small number of influences – Mod lasted 50 years, because it was a progressive, ever-changing moment.

Things that are Mod and things that aren’t Mod… there’s not necessarily that much between them. And I’m thinking of The Beatles, for instance, because, they went from wearing leather jackets, and having quiffs in their hair, to dressing in suits and being quite smart. They came down to London, they were they were influenced by Skiffle and American R&B. But no one would say they were Mods…

You have perfectly touched upon the dilemma of Mod. Beatles and Stones: Beatles, not Mod. Stones, Mod. Although with the exception of Charlie Watts, and maybe Bill Wyman, The Stones wouldn’t have called themselves Mods, but the reason they are regarded as part of the Mod Pantheon, from our perspective, is because they play proper blues. They chose blues at a time when mods were into blues. Whereas with The Beatles, Merseybeat is great and lovely, but it’s just that The Stones were darker, dirtier and deeper. But I should, at this point, say there is a great quote from Sonny Boy Williamson, when he was backed up by British bands on his first British tour. He said, “Wow, these British boys want to play the blues so bad. And yeah, they do play the blues, so bad”. We wanted to do it, but we couldn’t do it.

This British Mod Sounds of the 1960s box set has 100 tracks on it. That’s a lot of music. What kind of rules or boundaries did you set when you were looking for what to include?

Some of those boundaries was set for me, by what I could licence and what I couldn’t. Some companies won’t licence product, so [that’s why] The Who’s not there. Van Morrison’s Them is not there. I even spoke to Van Morrison and said, I want to put ‘Mystic Eyes’ on this record and he said – this is the genius thing – he said “Is Cyril Davies on the box?” and I said “Yes, he is” and he said “Alright, you can have it”. Trouble was, when it came to actually getting the licence included, there were so many hurdles to jump, I couldn’t get it. But the fact that Van was prepared and aware of the fact that Cyril Davies was a Mod… [was amazing]. You know, he was a sheetmetal worker from up north, who played amazing Rhythm and Blues harmonica – that’s Mod!

Putting the licensing restrictions to one side, were you just choosing your favourite Mod records from that era?

No, that’s a good point. One track per band. And believe me, it would have been very easy to have more than because some of the bands were out and Mods…

…Although you’ve snuck Rod Stewart on there twice?

Three times! He’s on Quiet Melon, there’s Rod and PP Arnold and there’s Rod Stewart as a solo artist. However, they’re all different projects. What was the criteria? ‘Would Mods have liked it?’ That’s it.

It’s interesting, because Rod is obviously a big name, Bowie’s on here, Elton (Bluesology) etc. Do you think there was an element of them jumping on a bandwagon that would hopefully carry them somewhere else, or do you think that was a genuine love of that music, from those artists, at that time?

That’s a really good point and no one has ever asked that question before. What I think is that the zeitgeist at the time, which went from Skiffle to Blues to R&B to Soul, I think all of those kids that ended up in those bands grew up through that. There was nothing else for them to like. You know, trad jazz ended up in a cul-de-sac with nobody playing guitar, and this was about guitar, mainly. Lemmy is on this box set [The Rockin’ Vickers] and I think, all of these people, if they hadn’t done what they did, rock wouldn’t have happened. Proper rock wouldn’t have happened. And that’s kind of pretty obvious, I think.

Yeah, because four or five years down the line, Bowie’s got long, curly hair and singing ‘Memory of a Free Festival’.

But fuck me, Bowie’s Mod stuff is good. There was a sea change and the sea change came about with British songwriters. They all did covers but then suddenly you have people like, Townshend, Marriott & Lane and Ray Davies writing, anthemic British songs about British working class life. And that’s when it changed. So there is more before that and more after that, but that’s what made it change into what it became, in about ’65/’66.

What happened to the original Mod movement? Did it just naturally fizzle out with a lot of these bands that never made it through to the end of the 60s?

I think it split into three. We had, I suppose, what were called Hard Mods, which became known as Skinheads in ’66/’67. We had the psychedelic bands, I mean, Pink Floyd were a massive Mod band and I tried to licence them. They did a fabulous Bo Diddley track, but of course you can’t get anywhere near them, especially not the Syd stuff. A lot of those bands went from Mod R&B/Soul and Mod power-pop, I suppose, to psych stuff, heavy stuff and became hippies. And then you had the people that stayed as Mods, and I suppose the main group like that was Love Affair who were are on the box set and who had a number of number one, I think, with ‘Everlasting Love’. Probably the last Mod hit record in ’68. So it kind of fragmented, became uncool, and disappeared underground. But it didn’t just disappear underground in the north. It carried on and changed. There was always Mods up until ’73 in the north, and then they became Northern Soul boys.

So what’s the relationship between Mod and Northern Soul?

Northern Soul sprung from the Mod sound. The idea of rare soul music played in a discotheque, by the likes of Roger Eagle, or Guy Stevens, became the main face of Cool Mod. Small Faces and The Who became Teenybop Mod. I hate to say it, but you see the Small Faces after ’67 and you’ve got 1000 teenage girls screaming – that is not cool. So I think, if anything, Mod disappeared with the fashion for Carnaby Street the Swinging London but it’d be more realistic to say it went underground,

I guess that’s the nature of a movement, isn’t it? It lasts for a certain amount of time, goes away and then might be revived, like Mod was in the late 70s.

I think the changes in youth culture got faster and faster and faster and Acid Jazz [the label] experienced this. Acid Jazz as a scene, was quickly replaced by Britpop, a year or two years later. But everybody who likes Acid Jazz didn’t like Britpop – it’s a different type of music. So Acid Jazz became Trip Hop, Trip Hop then merged with what was called hardcore, and Drum ‘n’ Bass, and became Jungle… So everything constantly evolves. The thing about Mod is, it always looks relatively cool. It’s hard to explain, because it’s not a constantly changing fashion, it’s a philosophy that can be applied to any aspect of your life. Paul Weller was eloquent about it. Mod is: ‘What socks do I put on today?’, ‘What books do I read?’, ‘Where do I go for breakfast?’ You know, ‘what coffee do I have?’ That’s Mod.

Do you feel like that every day?

Yeah, of course I do [laughs]. But I suspect that many of the fellow travellers on the path, do. And the thing is, it gets frozen in aspic, like anything. If you were 21 or 22 when you discovered Mod and you like this particular stuff, you’ll like that forever.

Especially in terms of the fashion. It seems to be something where it’s it’s easier to hold on to it, as you get older.

Why is that? Have you thought why that is?

Probably because it doesn’t involve wearing a cape and having long hair.

New Romantics at 50 look like sad old blokes in kilts and make up. Mods at 50 look like cool blokes. You can’t be a punk or a New Romantic at 50, because you look shit. But Mod? You can dress like a Mod. There’s a really cool guy called Jeff Dexter, who was one of the first Mods in London, he taught the Quadrophenia people how to dance, he produced America, you know, the best British folk band of all time. He’s a legend. He’s still a fucking Mod, and he’s got to be in his late 70s. Mod is not for Christmas, it’s for life [laughs]. That’s a terrible fucking line…

If someone buys this compilation, there’s 100 tracks, four CDs, they get the nice booklet with your intro, but at the end of the day, they’re listening to the music, they’re not thinking about scooters or wearing Parkas or whatever it may be. So what do you hope that people – who are maybe new to the whole 60s Mod thing – what do you hope that they might take away from listening to this music? What is it going to give them?

I don’t know! [laughs]. No, let’s be serious. Here’s a bizarre thing that happened to me at the weekend. I’m in a pub, and a kid, about 16 or 17 comes up to me and says “I just want to say this: You look fantastic” [laughs] and I’m just down the pub, you know? And he goes, “Are you a Mod?” And I’m 58, he’s 17. I said, “Yeah”. And he tells me that he’s watched Quadrophenia, he loves The Who, he’s done this, done that and he wants to be a Mod. I don’t know why or how it happens. It’s just something that happens, to maybe one in a hundred people.

The journey some of the artists on this box set make is very interesting, because a lot of people think of Tom Jones, they obviously think of, ‘Delilah’, ‘It’s Not Unusual’ and they think of him singing in Vegas in the 70s, hanging out with Elvis. But you don’t necessarily think of Tom Jones as a Mod and that’s what’s great about his collection, I suppose. A lot of it is like reframing what you might think about certain artists. Most Bowie fans know, or are aware of, the ’60s stuff, but many people don’t realise that before ‘Space Oddity’ he had five years where he was doing all sorts of stuff.

The best thing, and I’ve looked into this greatly, was that when Steve Marriott got thrown out and his own band – Steve Marriott & The Moments – and Bowie gave up with the last of his three Mod bands, they were going to set up a band called David and Goliath. Can you imagine how cool that would have been? Steve Marriot about 5’2″. Bowie, what? 5’10”? But unfortunately for Bowie – or fortunately! – Marriott met Ronnie Lane. And that was it. I’m a massive fan of Bowie. I mean, Pinups? When he’s at his peak, he’s gone: “I’m going to do a tribute to all the fucking Mod bands from the 60s that I used to love”. That’s a massive Mod album.

This box set is almost like an alternative route through the 60s, if you never went that way in the first place. If you were into the big, mainstream stuff.

We couldn’t get The Stones on here and we couldn’t get the Andrew Loog Oldham Orchestra, either.

Are there any bands now you think of as Mod?

Miles Kane. Jake Bugg actually started off as a Mod, but the thing is, in the industry, these kids, these bands do well, if they’re mods because there’s still a massive latent underground Mod scene. And they come out and start playing that music. But the industry says, you don’t want to be tied to that particular thing. It’s like The Strypes , I think they were signed for 250 grand, they’re a band of 14 year old Mods from Ireland, signed by Elton John’s team, and the first thing they said was you don’t want to be Mods because it ain’t gonna work. And what happened? Nobody was interested afterwards. Miles Kane was probably the last successful Mod artists and he was 10 years ago. But there are Mods in other spheres of life: Martin Freeman, Sir Bradley Wiggins…

Hiding in plain sight! [laughs]. Do you think this box set might turn some people into Mods?

What it could do is give people like that kid I met in the pub, the Mod-curious somewhere to start, because this is probably the ultimate Mod compilation.

Is there going to be a part two to this?

It’s going to be called Down The Rabbit Hole: What Mod Did Next…

Thanks to Eddie Piller who was talking to Paul Sinclair for SDE. British Mod Sounds of the 60s is out now as a 4CD deluxe set, a 6LP vinyl package and a 2LP ‘highlights’ offering.

Compare prices and pre-order

Various Artists

British Mod Sounds of the 1960s - 4CD signed amazon exclusive

|

|

||||||

Compare prices and pre-order

Various Artists

British Mod Sounds of the 1960s - 6LP vinyl amazon signed version

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Compare prices and pre-order

Various Artists

British Mod Sounds of the 1960s - 2LP black vinyl

Compare prices and pre-order

Various Artists

British Mod Sounds of the 1960s - 4CD standard edition

Tracklisting

Eddie Piller presents British Mod Sounds of the 1960s Various Artists / 4CD edition

-

-

CD 1 (or sides A, B & C in the 6LP vinyl set)

- The High Numbers – ‘I’m The Face’

- The Bo Street Runners – ‘Bo Street Runner’

- Cyril Davies & His R&B Allstars – ‘Country Line Special’

- Tom Jones – ‘Chills And Fever’

- John Mayall & The Blues Breakers – ‘Crawling Up A Hill’

- The Koobas – ‘You Better Make Up Your Mind’

- John’s Children – ‘Desdemona’

- Shyster – ‘Tick Tock’

- Billie Davis – ‘Wasn’t It You’

- The Hollies – ‘Bus Stop’

- All Night Workers – ‘Tell Daddy’

- Kenny Lynch – ‘What Am I To You’

- The Frays – ‘My Babe’

- The Shots – ‘Keep A Hold Of What You Got’

- Mike Stevens & The Shevelles – ‘The Go-Go Train’

- P. Arnold – ‘(If You Think You’re) Groovy’

- Dusty Springfield – ‘Little By Little’

- The Poets – ‘Wooden Spoon’

- The Muleskinners – ‘Backdoor Man’

- Jimmy Winston & His Reflections – ‘Sorry She’s Mine’

- Rod Stewart – ‘Good Morning Little Schoolgirl’

- The Yardbirds – ‘Over Under Sideways Down’

- Bluesology – ‘Come Back Baby’

- James Royal – ‘A Little Bit Of Rain’

- The Rocking Vicars – ‘It’s Alright’

-

CD 2 (or sides D, E and F for the 6LP set)

- The Fleur De Lys – ‘Circles’

- David Bowie – ‘Can’t Help Thinking About Me’

- Georgie Fame & The Blue Flames – ‘Sweet Thing’

- Small Faces – ‘Don’t Burst My Bubble’

- Tony And Tandy – ‘Two Can Make It Together’

- Jimmy James & The Vagabonds – ‘Ain’t No Big Thing’

- Episode Six – ‘Put Yourself In My Place’

- Geno Washington & The Ram Jam Band – ‘Michael (The Lover)’

- Dog Soul – ‘Big Bird’

- The Organisers – ‘The Organiser’ (feat. Harold Smart)

- Rod Stewart & P.P. Arnold – ‘Come Home Baby’

- Wynder K. Frog – ‘Henry’s Panter’

- The Alan Bown Set – ‘Emergency 999’

- The Soul Agents – ‘Seventh Son’

- Timebox – ‘Soul Sauce’

- Harold McNair – ‘The Hipster’

- The Spencer Davis Group – ‘High Time Baby’

- The Zombies – ‘Gotta Get A Hold Of Myself’

- Manfred Mann – ‘Don’t Ask Me What I Say’

- The Top Six – ‘I’m A Man’

- Love Affair – ‘Everlasting Love’

- Madeline Bell – ‘Picture Me Gone’

- Cliff Bennett & The Rebel Rousers – ‘Good Times’

- The Beazers – ‘Blue Beat’

- The Penny Blacks – ‘I’m Coming Home To You’

-

CD 3 – (or sides G,H & I in the 6LP set)

- The Syndicats – ‘Crawdaddy Simone’

- The Attack – ‘Magic In The Air’

- The Kinks – ‘She’s Got Everything’

- The Clique – ‘Ooh Poo Pah Doo’

- The Truth – ‘Who’s Wrong’

- The Artwoods – ‘I Take What I Want’

- The Creation – ‘Makin’ Time’

- The Sorrows – ‘Take A Heart’

- The meddyEvils – ‘Ma’s Place’

- The Birds – ‘How Can It Be’

- The Eyes – ‘I’m Rowed Out’

- The Sneekers – ‘Bald Headed Woman’

- The Untamed – ‘My Baby Has Gone’

- The Quik – ‘Bert’s Apple Crumble’

- The Move – ‘You’re The One I Need’

- The Mark Four – ‘I’m Leaving’

- The Gods – ‘Garage Man’

- Waygood Ellis – ‘I Like What I’m Trying To Do’

- The Nocturnes – ‘Hay, That’s What Horses Eat’

- The Mojos – ‘Everything’s Alright’

- The Wards Of Court – ‘How You Can Say One Thing’

- Platform Six – ‘Money Will Not Mean A Thing’

- The Silence – ‘Down Down’

- Apostolic Intervention – ‘Madame Garcia’

- The Deejays – ‘Black Eyed Woman’

-

CD 4 (or sides J, K & L in the 6LP set)

- The Action – ‘Never Ever’

- The Carnaby – ‘Jump And Dance’

- The Riot Squad – ‘Anytime’

- The Spectres – ‘(We Ain’t Got) Nothin’ Yet’

- The Mike Cotton Sound – ‘Soul Serenade’

- Sharon Tandy – ‘Hold On’

- Quiet Melon – ‘Engine 4444’

- Ossie Layne Show – ‘Midnight Hour’

- Dave And The Diamonds – ‘Think About Love’

- Fearns Brass Foundry – ‘Don’t Change It’

- Simon Dupree & The Big Sound – ‘Reservations’

- The Habits – ‘Elbow Baby’

- Maxine – ‘A Love I Believe In’

- The Blue Rondos – ‘Baby I Go For You’

- The Mindbenders – ‘The Morning After’

- The Shapes Of Things – ‘Striving’

- Wainwright’s Gentlemen – ‘And That’s Just Like Me’

- The Richard Kent Style – ‘I’m Out’

- Sean Buckley & The Breadcrumbs – ‘No Matter How You Slice It’

- The Afex – ‘She’s Got The Time’

- Syd’s Crowd – ‘Times Are Good Babe’

- Tony Colton – ‘Further On Down The Track’

- The Troop – ‘You’ll Call My Name’

- Razor – ‘It’s A Hard Way But It’s My Way’

- Dave Anthony’s Moods – ‘New Directions’

-

CD 1 (or sides A, B & C in the 6LP vinyl set)

Tracklisting

British Mod Sounds of the 1960s Various Artists / 2LP vinyl

-

-

LP 1

Side A.

- The High Numbers – ‘I’m The Face’

- The Action – ‘Never Ever’

- The Hollies – ‘Bust Stop’

- Small Faces – ‘Don’t Burst My Bubble’

- Georgie Fame & The Blue Flames – ‘Sweet Thing’

- Tony And Tandy – ‘Two Can Make It Together’

- Jimmy James & The Vagabonds – ‘Ain’t No Big Thing’

- Geno Washington & The Ram Jam Band – ‘Michael (The Lover)’

- The Artwoods – ‘I Take What I Want’

Side B.

- Dusty Springfield – ‘Little By Little’

- The Richard Kent Style – ‘I’m Out’

- Bluesology – ‘Come Back Baby’

- Wynder K. Frog – ‘Henry’s Panter’

- The Organisers – ‘The Organiser’ (feat. Harold Smart)

- Timebox – ‘Soul Sauce’

- The Spencer Davis Group – ‘High Time Baby’

- The Syndicats – ‘Crawdaddy Simone’

-

LP 2

Side A

- The Fleur De Lys – ‘Circles’

- Rod Stewart – ‘Good Morning Little Schoolgirl’

- The Yardbirds – ‘Over Under Sideways Down’

- The Birds – ‘How Can It Be ‘

- The Creation – ‘Makin’ Time’

- The Carnaby – ‘Jump And Dance’

- The Eyes – ‘I’m Rowed Out’

- The Kinks – ‘She’s Got Everything’

Side B

- The Mike Cotton Sound – ‘Soul Serenade’

- Mayall & The Blues Breakers – ‘Crawling Up A Hill’

- The Alan Bown Set – ‘Emergency 999’

- The Quik – ‘Bert’s Apple Crumble

- Apostolic Intervention – ‘Madame Garcia’

- Madeline Bell – ‘Picture Me Gone’

- Sharon Tandy – ‘Hold On’

- P. Arnold – ‘(If You Think You’re) Groovy’

- Love Affair – ‘Everlasting Love’

-

LP 1

A type of coat with a hood, often lined with fur

Interview

Interview

By Paul Sinclair

17