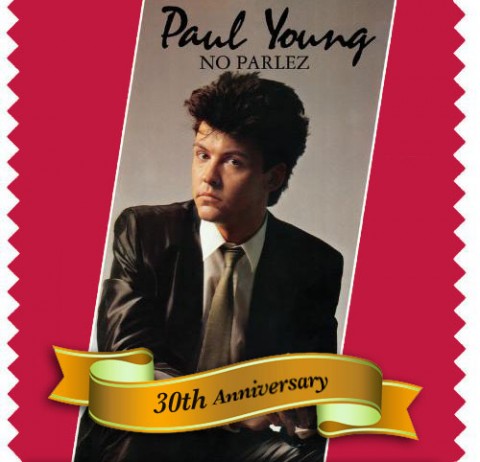

Happy 30th Birthday to “No Parlez” / Laurie Latham interview

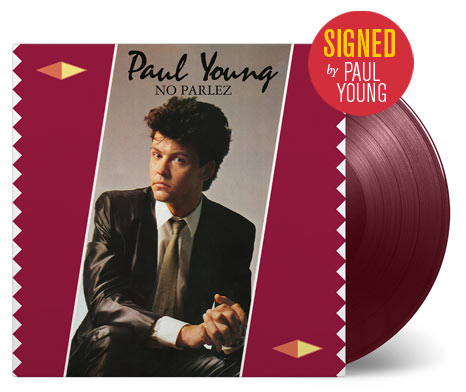

Paul Young‘s massively popular debut album No Parlez is 30 years old today.

The record reached number one in the British album chart and featured three singles that reached the top five in the UK top 40, including number one Wherever I Lay My Hat (That’s My Home).

As a way of celebration, we are publishing today an exclusive interview with No Parlez producer Laurie Latham about his work with Paul on his debut album, and the follow-up The Secret Of Association. The interview was to have been published in the booklet of Cherry Pop’s Remixes and Rarities compilation, but unfortunately space restrictions meant we could only include an excerpt.

Laurie Latham interview

SuperDeluxeEdition: How you look back on working with Paul, you must have fond memories?

Laurie Latham: Very fond memories. It was just one of those things where you had a look of talented people and it all gelled. It was great.

SDE: How did it come about that you ended up producing No Parlez?

LL: Mark Pinder, the drummer, who was a close friend of Paul’s, had done work on various projects with me before – playing drums on things that I’d done, including a post-punk thing called The Vampire Bats From Lewisham. We did quite a lot of messing around with extended mixes, and what have you, and when Paul was looking for someone to collaborate with, Mark suggested me. It wasn’t a trial as such, but the first thing I did was [work on] a demo of a song they’d done called Sex and basically I did an extended version of that. Paul liked it and we got the green light from CBS to do three or four tracks. Paul always insisted that was the best demo version, but it got lost somewhere.

SDE: Didn’t that demo end up on the No Parlez 25th Anniversary reissue?

LL: Did it? Ooh, maybe it did. I remember it went AWOL and Paul was rather upset that he couldn’t find it. Whether it’s the actual one, I don’t know.

SDE: Did you tend to edit seven-inch versions down from an original extended mix?

LL: What tended to happen was that some tracks were obvious singles, and they would get mixed and then go out. Often I would then maybe do a twelve-inch version, but we’d often like the twelve-inch version so much better than the seven-inch mix that we’d done, we would then cut that down more to make an album track. So some of the album tracks, certainly on No Parlez, are the twelve-inch version edited down – Love Of The Common People, for sure and Iron Out The Rough Spots. It depended on what order things came and the release schedule. It’s that thing where you’re freed up to do what you want [when working on a twelve inch] and you get all the happy accidents.

SDE: Can you tell us about I Was In Chains on the cassette of The Secret Of Association. Why was a long version created?

LL: I can’t remember [laughs]. I know it did go on for a bit, that track! The initial idea for that was to have a hybrid Sly & Robbie / Simmons drum type groove, with this folky feel to it. I remember I phoned up The Chieftains and tried to get them to play on it, but they wanted a ridiculous amount of money and they also wanted points [a royalty] so that was definitely out of the window, so we just improvised.

SDE: So there weren’t any discussions with the record company, where they told you to edit down I Was In Chains for LP and CD?

LL: There probably were, but I don’t recall any. To be fair to the record company, they gave us a lot of freedom when it came to the albums. With the singles, they were obviously a bit more careful, and a bit more opinionated.

SDE: With the odd exception, such as the US Mix of I’m Gonna Tear Your Playhouse Down, were all the extended mixes done by yourself?

LL: Absolutely, yes. Paul wouldn’t normally be there. With all the extended mixes they had much more sense than to be around, because really you’ve got to remember, we’re talking about tape machines, and sometimes I’d be there for days faffing around, mixing little four bar sections. If you see the master tapes – you probably have – it’s just one bit of sticky tape after another, going past the heads. Paul was fantastic, he knew that I was much better off being left to my own devices, and hopefully something good would come out of it. He had a lot of respect and faith in my creative judgement. Obviously a lot of the arrangements for the song were already done, so I was working with a finished piece anyway. But the arrangements would change. Suddenly the intro would become something that would happen in the middle, for example. So we’re all together for the serious stuff, working on a track for a single, but when it came to the remixes I’d be in the good old Workhouse [studios].

SDE: How long did it take to do the remixes, on average?

LL: It depends. Sometimes I’d do bits, call it a night and come back in the morning. Although it wasn’t our own studio [The Workhouse] – we had to pay a studio bill – it was very flexible. I had the keys to the place and I’m sure we ‘massaged’ the bill to an extent, me coming in at weekends etc. It depends on what period we’re talking about. With the second album we only did sections of it at The Workhouse. We did a lot at Park Gate, down in Sussex, and in Pathé Marconi in Paris.

SDE: Did you regard doing the remixes as fun – an opportunity to mess around – or a pain in the backside?

LL: No, absolute fun and joy. It’s a bit embarrassing listening back to it now, but we were just chucking everything in. Paul is so knowledgeable about music and he taught me an awful lot about certain genres of music and I’d come from a more a left field area and had done a lot of experimental, esoteric stuff, and brought that to the table. So it was a great melting pot of all these influences. Paul always seems to get written out of the history books when you’re talking about people from the eighties, because it was so eclectic and mixed up. It’s not like the Human League for instance, where it’s a very defined style. And the thread of course was Paul’s fantastic vocals. Once you’ve got the vocal on, you’ve got a coherent thread through the whole thing.

SDE: Why is there a version of the Extended Club Mix of Come Back and Stay with ‘scratching’ on it, and one without the ‘scratching’?

LL: I don’t know. You’ve got me there, Paul [laughs]. The whole meter of that track… it’s a bit all over the shop, it’s not something you could really dance to. It’s weird – you’re applying culturally these club-type things, but it’s not really a club record.

SDE: Which recording or performance or song from the first album or second album do you have the fondest memory of.

LL: The track I really like on the second album is Soldier’s Things, which is the Tom Waits cover from Swordfishtrombones. I thought it was a really good arrangement and still stands up. It’s not so over the top as some of the other stuff we’d done. I also like Everything Must Change.

SDE: You’d had success as a producer before, but how good was it having an American number one with Every Time You Go Away? That must have been a real buzz for everyone.

LL: It was. I remember doing the American single release mix at ICP [Recording Studios] in Brussels, [and] spending all night mixing that. I remember carrying that Daryl Hall demo around in my back pocket on a cassette for a long long time.

SDE: Tell us about Man In The Iron Mask.

LL: That was probably the quickest track we ever did. We were working at The Workhouse and I’d been talking to Billy Bragg quite a lot, with the idea of maybe working with him and I’ve known his manager, Peter Jenner, for years. I remember really, just banging it out. I don’t remember why, but I recall there was a cab waiting outside for Paul while we were doing the track. We had to get the vocal finished and he literally ran out and jumped in a car, and went off somewhere! Hence it’s just synths, almost a Blade Runner / Vangelis backing with a soulful vocal on top.

We used the OB-X 8 which was this lovely warm analogue synth. My manifesto which I presented to everybody when we started No Parlez was all these soul clichés that had gone before like Hammond Organ and brass, we’re not going to do. We’re going to mix synths with piano and guitar and unusual instruments, like marimbas. The first thing we ever did was Iron Out The Rough Spots and we got one of these marimbas with an extra octave down the low end and did that bass part on that, and build it all up. We were quite careful about what synths we used; the OB X and we used quite a bit of the old fashioned vocoders, the Korg Vocoder.

SDE: One of the big differences in the sound between No Parlez and The Secret Of Assocation is the backing vocals, because backing vocalists Maz and Kim – ‘The Fabulous Wealthy Tarts’ – don’t feature much on the second album. Was that Paul trying to get back to a more soulful sound?

LL: No, we were in Pathé Marconi in Paris and specifically for Everything Must Change we wanted that Ry Cooder / Bobby King backing vocals type sound. I’d already worked with George Chandler, Tony Jackson and Jimmy Chambers on some Anthony Moore tracks, so we got them in. Basically what happened was that Paul got so seduced by their sound, suddenly we were putting them on everything and the girls were put on the back burner and they were pretty upset about that, to be honest. That was certainly not my intention because I thought it was more unusual, with the girls and the things that they were prepared to try. But the guys were great as well, they were fantastic.

Laurie Latham was talking to Paul Sinclair for SuperDeluxeEdition. Remixes and Rarities is out now on Cherry Pop. Read our interview with Paul himself here.

Interview

Interview

By Paul Sinclair

5