#ZTT30 / One February Friday

On this February Friday, Rob Puricelli remembers the classic era of Zang Tuum Tumb – the excitement, the intrigue, the posters, the T-shirts and the records. Move with him inside the strange world of ZTT Records…

Who then, devised the torment?

Some would have you believe that the 1980s were a decade of decadence and poverty, two social polar opposites created by Thatcher and her cronies. Some would have you believe that it was the decade that style forgot and also the one that gave birth to groundbreaking design. If anything, these statements go to prove that this decade was all about change, diversity and a nation, nay a global society, emerging from gloom, oppression and a desperate lack of creativity.

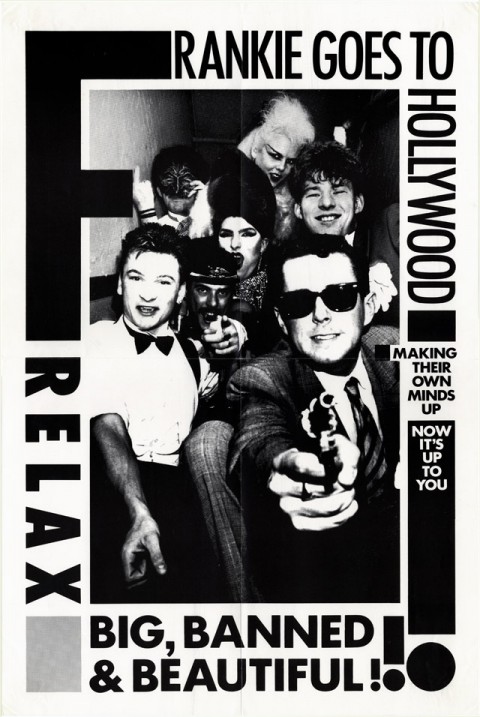

In 1984, when Frankie Goes To Hollywood finally topped the UK charts (it had taken three months from the day of release) with their debut single, Relax, I was 13 going on 14. I was impressionable. I was confused and in need of a fashion to follow or, at the very least, the inspiration to set a fashion of my own. The 1980s were tribal, which was strange as everyone was trying to be different. For the first two years of that decade, I wore a large white stripe across my nose, had braids in my hair. That was followed by burgundy Sta-Prest trousers, college cardigans and loafers. After that, it was red Levi jeans and white boots with a ‘Fame’ logo emblazoned on them and muscle shirts (ironic as, aged 13, I had little muscle mass on my scrawny arms). But for a while, in 1983, I felt a bit lost. Puberty had long since kicked in and the refuge that music had always provided was not quite enough anymore. I flitted from one synth band to another until one October Monday, when a fledgling UK record label released a record that would forever change pop music – those that listened to it and those that made it. That might sound like a grandiose statement, and one tinted with a hint of rose. But it really did. And, more importantly, so did the label that released it.

Zang Tuum Tumb.

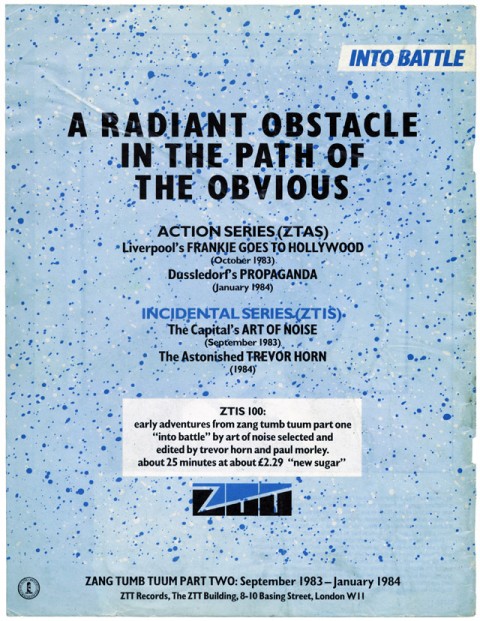

Just read that again. Say it out loud. Go on… a few more times. It makes no sense. It’s nonsense. But it intrigues you. And if you’re a thirteen year old impressionable kid, it bothers you somewhat. However, it also has the potential to empower you. If you can figure out what it means, you’ll have one up on the other kids in the 3rd year common room. Moreover, for a kid like me, seeing the ZTT adverts in the music press of the day, they created an even more tantalising air of mystique. We all want to be clever. Or smart. Or both. Especially when we’re kids. Exclusivity and oneupmanship on the playground is a matter or life and death as far as kids are concerned. And it was no different in 1983, moving rapidly into 1984. I was more than a little disappointed when I discovered it was a series of onomatopoeic words to describe the sounds of a machine gun, written by Italian Futurist, Marinetti. Although I did pride myself on having heard of Marinetti, only because he gets name checked in Animals & Men, a track by the first incarnation of Adam & The Ants on their Dirk Wears White Sox album.

ZTT seemed mysterious. Its messages were wrapped in enigmas and smothered in intellect. The imagery was sometimes vague, sometimes amateurish. The fonts were big and bold or, conversely, tiny and almost illegible. It seemed that wherever space existed on a page, there was room to fit in another obtuse quote, another bizarre line, a swear word or credit. And then, of course, there was the music. One could be forgiven for thinking that with all the artistic and cerebral pretensions of the marketing, the music might be equally aloof and unfathomable, appealing probably to the creative elite and cognoscenti. That was until, in the case of Relax, you heard the pounding bass line on every quarter beat of the bar. Oh my, this wasn’t hard to work out. It didn’t need a degree to understand the primeval, rhythmic pounding. Far from it. This was simple stuff. This was designed to appeal to ones very primordial core. It was raw, essential, life affirming, life imitating, sonic candy. The snarling vocal, the innuendo of the sound effects, the quirky backing vocals, the cutting synth lines, the massive space in which all these sounds resonated and interplayed. This wasn’t complicated stuff for the ears. This was elemental.

For some years previously, independent record labels had become the driving force in music. It was on these labels that one found the best, most raw, most relevant artists. Labels run by the bands and the fans, who saw it as a way of expressing their collective voices. Through the music, through the handmade sleeves with their hand drawn artwork and through the low level distribution, the angry youth, long dismissed and forgotten by successive and brutal governments from both sides of the house, had found a way to make themselves heard, and in turn, make themselves relevant once more. Being on an independent label was cool. Running one was cooler and I’m guessing that’s what attracted Paul Morley to it.

Paul had long written about music in the NME as one of its Manchester based journos. He had made a name for himself as verbose, opinionated, witty, sarcastic, caustic and pompous. Overall, he got you thinking and he got people talking. And he’d witnessed, first hand, the birth of the greatest and most ridiculous, yet astounding, and enigmatic indie labels ever. Factory. A label who gave its artists free rein and 50% of everything; who indulged in artistic pretentions and had a roster of enormously diverse artists. In 1984, I had barely heard of Paul Morley, and yet it was his words that were puzzling me, drawing me in and guiding me to a bright, musical light.

And the man behind that musical light was a man who I had previously fawned over when I first encountered him as the lead singer of Buggles. I didn’t realise it back then but those silky production skills were to blow my tiny mind just a few years later. I’ve got books, both historical and academic, on his skills and prowess, that I have repeatedly read. I’ve watched countless documentaries. I’ve even been in the same room as the man when he’s given Q&A’s and lectures in person, yet I still can’t figure out what it is that he does that makes everything he touches turn to sonic gold. He has this uncanny ability to create immense space in a mix, allowing every element to breathe. But he does ‘it’, whatever ‘it’ is. And he did ‘it’ back then too, and I guess Paul saw ‘it’ and saw how ‘it’ could change the way music got made and how ‘it’ would be consumed.

Of course, with two masters in their respective fields, there had to be the sensible, realistic and calming influence. That was Trevor’s wife, and businesswoman, Jill Sinclair. She kept their wild imaginations in check and ensured that work got done and out of the door in order to keep things going. But we’re not here for a history lesson. Received wisdom usually takes care of that. There are many tales of legendary status that surround ZTT, its artist roster and its business practices. I’m not here to indulge in that, nor rewrite history a further time. No, I am here to share with you what it was like to be a consumer of all things ZTT. Because I was their target market. I was representative of the youth demographic that the pop music they produced was aimed at. I was sucked in to the hype, the silliness, the seemingly exploitative nature of their actions and incidentals. Let me get back to the label, and the culture of the ‘indie label’ back then. Because they don’t really exist any more. And it’s important that we understand them.

Indie labels were more than just a way of musicians and artists to get their work out. As a consumer, they were as important a badge on a teenager’s Harrington jacket as the badge that bore the name of their favourite band. You followed labels like you followed bands. Especially the independents. Independent labels weren’t part of the system. They weren’t faceless corporations, hell bent on exploiting us for every penny of our pocket money or paper round wage. Indie labels were far more than just an outlet. They were an identity. And we latched on to that. Like I said before, the eighties was this beautiful dichotomy of polar opposites, of individualism and tribalism. Each band might have had their own image or style or way of presenting themselves, but every act on the books shared label DNA. Each release had a common aspect to them, united by the brand of the label. It might not be words or pictures but it could be a sentiment, or a series of connecting statements scribbled in the run-out groove. Being a fan of an indie label was akin to building a jigsaw but nobody knew what the final picture would be. Every element connected to every other, even with the most tenuous of links. As time progressed, indie labels became more bold, more adventurous and more influential. There were hundreds of them. Some were bigger than others but all of them shared a philosophy of making and sharing music for the sake of the music rather than the filthy lucre. ZTT were not that different, except they owned one of the most famous and iconic studios in the world, mainly because Chris Blackwell of Island Records sold it to Trevor Horn on the understanding that Trevor would form an indie label and operate it under Island’s banner, and Trevor was, arguably at the time, the greatest music producer in the world. Add to that the words and artistic guidance of, probably in his own opinion rather than that of the rest of us, the greatest music writer of his generation and you had the right mix to make things happen. And boy, did they make things happen.

Relax was the perfect start. Look at the cover, the front of which was illustrated by Anne Yvonne Gilbert, the overall design by XL and you just don’t know where to begin. There are bizarre statements scattered around its unusual layout. These statements are chaptered. Some of the quotes seem deep and meaningful, others downright offensive (to some). Even the band credits give each member more than just a nod to their instruments of choice. And then there’s that front cover. Considered pornographic by some at the time, there is nothing that offensive on show. No dangly or wobbly bits. But it was wonderfully erotic for both gay and straight people. For me, it was the thigh high socks worn by the lady and the fact she clearly had no knickers on. You couldn’t see anything, but like the best horror movies, the thrill was in what you weren’t shown, not what you actually saw. Of course, the lyrical content, the chorus of which was emblazoned on the front cover, left little to the imagination, no matter how coy Holly Johnson was in interviews when questioned on their meaning. But the best bit was going to buy it. I ventured into my local Woolworth’s store, if my mind serves me well, and took it to the counter with equal amounts of excitement and embarrassment. A bit like having sex for the first time. And I still believe, to this day, that those feelings were the intended response that Mr Morley wanted.

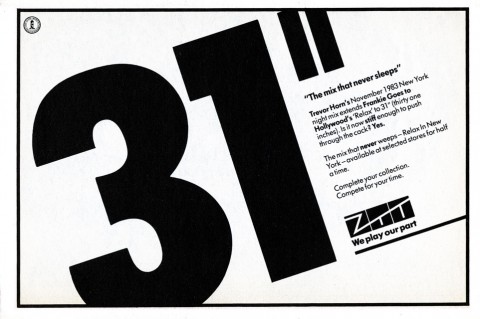

Getting it home, I listened to it and was confused by what I heard. Sixteen minutes of something that sounded like Relax, but never truly got there. I shared the experience with friends and it didn’t take long to discover that there was more than one version. I went and bought the seven-inch so I could at least indulge myself in the actual song and its melody, but the mixes intrigued me. Bear in mind that, in 1984, there was no internet. We couldn’t Google, or pop onto a web forum. We found this stuff out by talking to other friends or the weekly updates in the music press. And it was here that Paul Morley rallied us, his troops. Tantalising adverts that spoke of special versions, unique re-workings and the remix. It was through these advertisements, many of which were designed in conjunction with Tom Watkins’ XL design house, that he made us all collectors. None of us wanted to miss out on what might be a better or longer mix than the one we had just purchased. Yet again, there was this manufactured air of exclusivity where we would try to outdo each other with our mixes, almost like a game of twelve-inch Top Trumps. But it wasn’t just the music that changed, it was the sleeves or the record centres too. Seemingly not content with what had gone before, ZTT found it necessary to rework and remix, improve and move forward, taking us with them, seven or twelve inches at a time. But little did we know that Relax was merely the beginning.

When Frankie followed Relax up with the magnificent Two Tribes, the variations became more wild and diverse. As did the artwork and sleeve design. With Two Tribes, we moved on from sex education and began to be educated in the politics of the Cold War with Frankie tapping into our nascent political ideals, nurturing our very real fear of hostile nuclear attack. Statistics on the potential nuclear apocalypse sat next to survival tips for when the bombs started dropping. Images of Soviet power were offset by those of overt American patriotism. Little did we realise back then that these images were depicting the same thing. Fierce national pride and a willingness to protect it at all costs, with the rest of us as unwilling victims; mushroom cloud fodder, if you will. The twelve-inches came thick and fast. One version even relegated Two Tribes to the B-side, effectively, making way for the funky Edwin Starr cover, War. Annihilation Mixes made way for Carnage mixes with some Hibakush-ah thrown in for good measure. The mixes on the cassette single aka the “cassingle” (a carrier format whose invention we have ZTT to thank for) were different again. And let’s not forget the video, a Godley & Creme affair that pandered wonderfully to the MTV generation. Rumours whipped around the common room of the existence of even more mixes and who had found them. Many of these mixes were figments of our imagination, as it turned out. As I alluded to earlier, there was no internet. These things had to be bought. They rarely got played on the radio and so, armed with your pocket money or hard earned Saturday job wage, you ventured into towns and cities, to the plethora of record shops, to see if you could unearth these prized gems. And none of this was made any easier by ZTT’s mischievous marketing. Some adverts were for products but some adverts were merely manifesto statements and it was these statements that built on the enigma of the label itself, elevating it far beyond the cottage industry that allowed it to be born and to flourish. I mean, adverts that didn’t actually advertise any product that they were selling? Really? Yup, really. That, as the kids say today, happened.

When the Frankie album finally came to be released, things went up a notch. Big TV ads, voiced by David Frost, proclaimed the arrival of Welcome To The Pleasuredome as if it were the saviour of all pop music (and in my very humble opinion, it actually was). An audacious double album, no less. Releasing a band’s debut album as a two disc affair was a bold move indeed and one rarely undertaken by the big majors, let alone a pubescent indie. The hype was in overdrive and I even snuck out of school at lunchtime to buy it, facing all manner of punishments if caught. I made it back in time to smuggle it into the common room and onto the communal record player. We tucked it into the corner where we hung our coats and all of us formed a human igloo around the turntable as I dropped the needle and the operatic voices and big orchestra hits started to flow. I don’t think that kids nowadays have ever experienced moments like that. I desperately hope that they do, but I’m far from confident.

After the excitement of Two Tribes came The Power of Love, their pre-Christmas No.1 and their record equalling third consecutive UK chart topper. This time, after dealing with sex and war with consummate ease, they decided to tackle love and religion. The song was a love song, the video was a blatant Christmas nativity piece, cynically going for the coveted end of year chart topper, only to be held off by Band Aid. But it didn’t deter us kids, and we lapped it up. Single number four, the album’s titular track (and my personal favourite) fared less well but had similar mix treatments with the rather splendid Fruitness Mix being a personal favourite.

But it wasn’t just Frankie. Some may find this apparent bias unfair, but they were the explosive start and I feel justified in using them as such. They were the initiation to the gang. They got you hooked onto the label and then you just had to look around for more. For example, on the inner sleeve of disc 2 of …Pleasuredome, they had listed some merchandise for sale, with the centre hole of the inner sleeve serving as the order form. Modelling the aforementioned merchandise was Paul Rutherford and a bespectacled, odd looking but definitely attractive blonde woman. Who was this bizarre lady, standing in a duffle bag? Upon investigation, it turned out to be Claudia Brucken, singer in ZTT label mates Propaganda. Their debut single, Dr. Mabuse was released a few weeks after Frankie hit numero uno with Relax. It was also subjected to multiple remixes and was a reasonable hit in the UK. But even though their deserved success was overshadowed by Frankie – so much so that their second single and first album came over a year after Dr. Mabuse – we had to check them out because they were on ZTT. The same could be said of Andrew Poppy. If you had come to me at the age of 14 and told me that I would develop a taste for the works of a minimalist composer, I’d have told you to get lost. But I did, because Mr Poppy was on ZTT. As simple as that.

Propaganda became a firm favourite of mine, for what it is worth. Not quite as in your face as Frankie, but at least we now had ladies to adore and worship. And there were so many ZTT production cues in there to make the music instantly appealing. For example, they used the same percussive element that was found across many Frankie tunes; the hi-hat/cabasa/tambourine part with emphasis on the two and four beat. It generates a shuffle that implies movement, accentuating the important one and three beats essential for dancing. Listen for it in the Frankie tracks Welcome To The Pleasuredome and Two Tribes and the Propaganda tracks Frozen Faces and Dr Mabuse (where the pattern is played more with the drums). Claudia still performs today, is still strangely attractive and still has ties with ZTT. After the disbanding of Propaganda, Claudia teamed up with Thomas Leer, a Scottish musical genius with a Fairlight, and they formed the solitary album producing Act – but what an album. Produced by Trevor Horn’s right hand man, Steve Lipson, who had done most of the production work on Propaganda’s A Secret Wish, the album fused pop and politics with technology and style. Far from commercially successful, the three disc anthology, released in 2004, suggests there was far more potential than that one album gave them credit for.

Frankie returned with Liverpool, less well regarded and incorrectly so. It still has the vibrancy of their first but by now, they were no longer the novelty they once were. Time had passed and others were now following in their impressive footsteps. Liverpool lacked the headline grabbing impact of their first batch of releases and in a world obsessed with always finding the next big thing, Frankie just weren’t that anymore. And, of course, things had started to deteriorate within the band itself. Just watch the video for Watching the Wildlife. Mark looks like he’d rather be up the pub drinking a pint of vomit. The promo for Warriors didn’t even feature the band, apart from some poorly animated stills. They burned very bright and they burned less than half as long.

I can’t believe I have got this far without mentioning either Art of Noise or the Fairlight.

Art of Noise was where ZTT had started, born out of the leftovers of recording sessions for Malcolm McClaren and Yes, where the Fairlight CMI, a wondrous and game-changing computer and musical instrument hybrid device that has been my passion ever since, supplied new sounds and inspiration. Morley took this, added more Italian Futurist leanings (the very name of the band is from an essay by Russolo) and began to propel this shadowy collective of highly skilled and diverse musicians, engineers and producers into the psyche of not only the arty, farty world of pop but also to the kids on street level. Art of Noise, a bunch of well educated, middle-class English men and women ended up becoming the inspiration for hip hop. Sounds ridiculous? Of course! But it happened, and it happened because of ZTT. Because of Horn and Morley, because of Langan, Dudley and Jeczalik. Sadly, like most ZTT acts, Art of Noise went through some changes that saw Horn and Morley leave, followed shortly by Langan, with the remaining members finding more success by signing to China Records and reimagining dodgy fifties based themes such as Peter Gunn or Prince covers with the likes of Tom Jones. For me, Art of Noise had sold out for the big bucks and had become a parody of themselves. Gone was the experimentation and quite frankly, the rest of the pop world had caught up with the once exclusive technology, with Emulator’s and Akai S1000’s coming in at 90% cheaper than the once groundbreaking Fairlight. Thankfully, some years later, after J.J. had quit to become a school teacher, Anne rejoined with Trevor, Paul and Lol Creme, to found AoN v3 and release the superb Seduction of Claude Debussy long player, back on ZTT. Subsequently, there has been a spate of re-issues from the ZTT archives and people are once again able to dive into the surreal ‘music concrete’ of Mr Morley’s initial vision. I guess if any one act on the ZTT roster sums up ZTT, it has to be Art of Noise as it completely represents the daring nature and bravado of the imprint, as well as the pomposity and aloofness of it all, delivered, as always, with a tongue planted firmly in someone’s cheek and a po face.

ZTT, or moreover Paul Morley, also introduced us to the concept of the ‘Series’. It was almost like having mini labels within an overarching umbrella label. Essentially, it was like departments in a store. There was the Action Series, for the hits. There was the Incidental Series for less commercial stuff. Even today, the concept remains with the Element Series. This further reinforced the collectibilty of the label’s output. For someone like me, who sits around halfway on the OCD scale, this is like pouring kerosene on an already raging fire. It’s often been said that the multiple twelve-inch singles, cassettes and videos were merely a ploy to get people to buy stuff more than once, or to help with chart positioning. The latter may have a degree of truth to it, especially as the company behind the UK chart compilation changed its rules shortly after Two Tribes became a nine week No.1 hit. But I never felt ripped off because each release WAS different. They were almost always completely different. Different sleeve art, different tracks and different mixes. We didn’t realise it at the time, but the true art of the remix was being forged, right here. How many versions of a piece could be made that stood up by their own merits yet retain enough of the original DNA to remain familiar? Today, remixes are churned out and barely contain any of the original, besides the track title. But what Trevor aspired to do was create new stuff with the same ingredients. He revisited the song, its elements and spirit and stripped it down to its constituent parts, then reassembled them so that it was new, different and still identifiable. The twelve-inch remix had been born as a way of extending dance tunes for the club scene. What Trevor did was to take that one step further and make that extension interesting, rather then repetitive.

Of course, we mustn’t forget the merchandise. By today’s standards, it was fairly restrained but what self respecting teenager didn’t want a Frankie Say t-shirt? The simplicity of Katherine Hamnett’s design of black text with one word much larger than the rest, on a clean, white ‘Fruits of the Loom’ cotton shirt made Paul Morley’s statements stand out loud and proud. And what statements they were…

Frankie Say Relax Don’t Do It!

Frankie Say War! Hide Yourself

Frankie Say Arm The Unemployed

I scrimped and saved and bought a ‘War!’ shirt, but for the life of me I can no longer find it. It either got stolen by an ex girlfriend or thrown out by my mother. Either way, it’s gone and they’re fetching three figure sums on eBay. I have pleaded with the powers that be at ZTT to release them again, especially in this 30th anniversary year, but my pleadings seem to have fallen on deaf ears.

All of these things were pieces to a puzzle, but it seemed that nobody knew what the final picture would look like. The sleeve notes, the tantalising messages on the spines of sleeves or cassettes, the riddles contained in press adverts, it’s as if we were playing a game of join the dots. They all pointed toward a grand plan, a collection of art that was being assembled and curated at the same time as it was being gestated and created. It made you feel part of it. And I suppose that’s what all great movements do. They make you feel part of something, whether you are fully aware, or fully care about it. Teenagers need to belong to something that their parents don’t. There have been many musical movements, some of which were epic and widespread, others that barely moved off the sofa, but they pass the masses like trains on a station. The brave ones jump on the faster moving movements/trains. For their bravery, they are rewarded with notoriety and excitement. The rest of us play it possibly a little safer and jump on the slow ones, which ultimately last longer, but are sometimes bereft of passion and vibrancy. ZTT, for me, felt like something in between, chugging down the middle, between the two. Frankie, were over within three years of Relax hitting number one. Propaganda were, tragically, over before their criminally delayed first album. Other label mates came and went. But it didn’t seem to matter because ZTT never seemed to be about standing still. It was about expanding the mind and breaking new ground. The sheer diversity of musical styles on the label was sometimes confusing, but it meant that they always seemed to have a relevant act on the books. For the music fan, this was sometimes troublesome because in the past, most indie labels were created on the back of particular musical movements or trends. I give you Two Tone or Mute as examples. But with ZTT, you had everything from pop to soul to classical and hip hop. Morley tried to wrangle them into his blueprint, but by the nineties, the label’s identity had become too diluted and artists simply wanted to make their own music, their own way and on their terms.

But ZTT was a badge I wore with dubious honour. It was a way that I could wear intellectualism on my sleeve, right next to a love of throwaway, mass-market pop. It represented rebellion as equally as it did order and conformity. But then, I guess this is no surprise when you look at the two driving forces behind the label. There was an equilibrium, albeit one that resembled Jekyll & Hyde.

These are my rambling and random thoughts, recollections and impressions of this unique label, its equally unique assemblage of artists and its particular moment in time. The facts may be a little skewed, but the sentiment is as true as can be. To this day, I treasure my ZTT artefacts. I’m not an avid collector by any stretch of the imagination and I rely heavily on the likes of current ZTT label manager, Ian Peel, and his magnificent curation of the ZTT archives, to plug gaps in my collection of remixes and rarities. I’ve nagged him repeatedly to take me to the fabled ZTT vault but I think he knows that if he did, he’d probably never get me out. I still pore over every ZTT release though, sometimes chuckling, occasionally puzzled, always satisfied.

But artefacts these pieces are. They are markers in my personal history and they combined entertainment with education. They spurred me to discover new music and at the same time, research the intellectual references and broaden my cultural knowledge. ZTT, for me, represents a wonderful coming together of artistic concepts that rarely coexisted before, and that, in my humble opinion, hasn’t ever done again since. The label married together the incompatible in such a way that it seemed obvious and natural to do so. From the crass to the classy, from the masses to the minority. Music, visuals, poetry, t-shirts, slogans, manifestos, hit records, massive flops, intelligence, ignorance, gay, straight, asexual, over-sexual. There was something for everyone and nothing for no-one. All done for the sake of the art, but maybe not the artists. Much like the label Morley had witnessed in Manchester, not ten years before.

ZTT. The Factory Records of the South. (only ZTT is still going and they didn’t make a loss on the best selling twelve-inch of all time)

Rob Puricelli – One February Friday, 2014

Reviews

Reviews

By Paul Sinclair

14