Luke Haines on The Auteurs

The SDE interview

The Auteurs were a British ‘indie’ rock band whose 1993 debut album New Wave was lauded in the press and was runner up (to Suede’s debut album) at the Mercury Music Prize awards in 1993. Fronted by singer and songwriter Luke Haines, the band would go on to record three more albums in the 1990s with Haines occasionally taking a left turn for side projects such as the Baader Meinhof album in ’96 and forming Black Box Recorder with John Moore and Sarah Nixey, whose debut England Made Me was released in 1998.

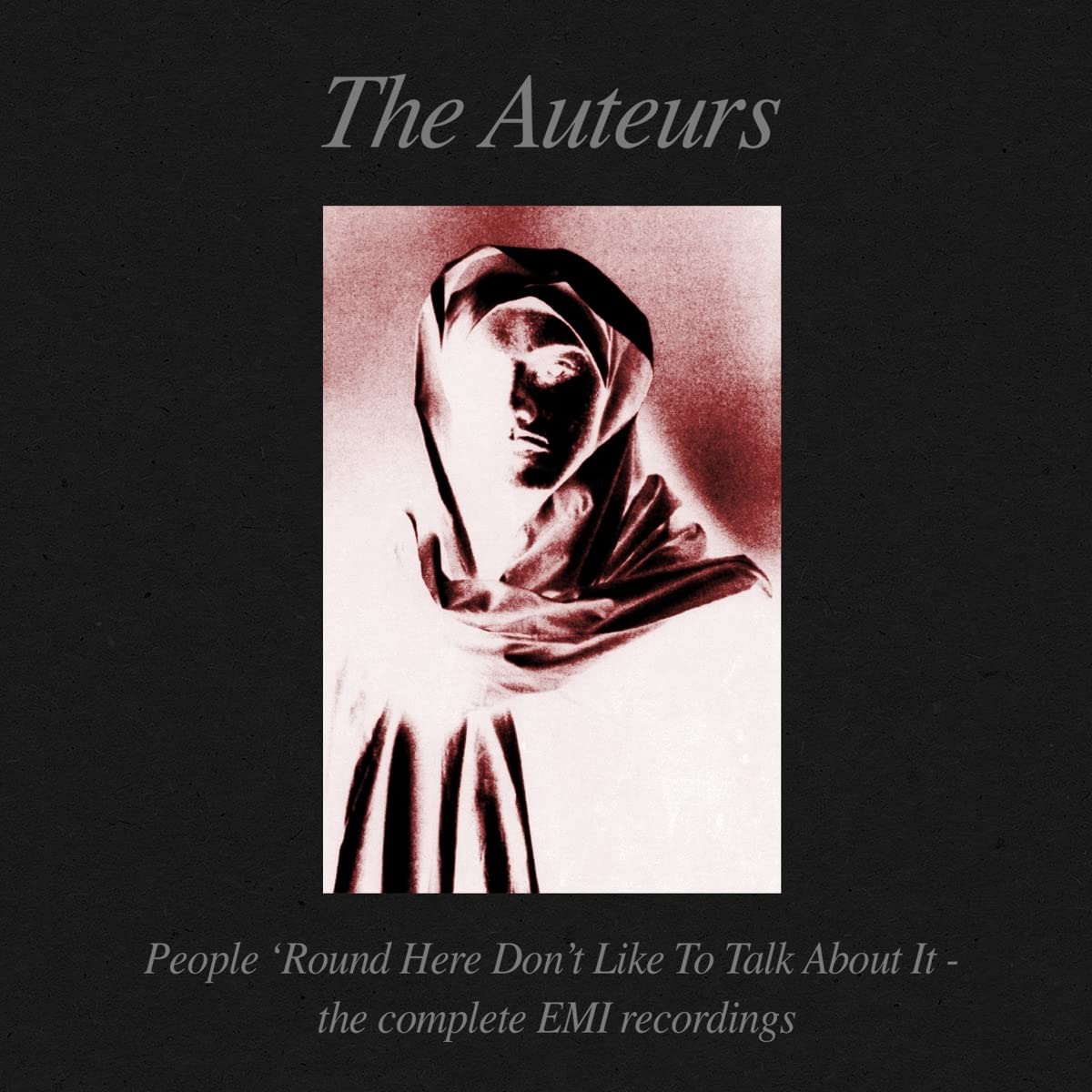

Last month, Cherry Red issued a comprehensive 6CD Auteurs box set called People ‘Round Here Don’t Like To Talk About It: The Complete EMI Recordings, which brings together all four studio albums with a wealth of bonus material, the Baader Meinhof record and Das Capital a semi-orchestral collection of re-recorded Auteurs tracks that Haines put out in 2003.

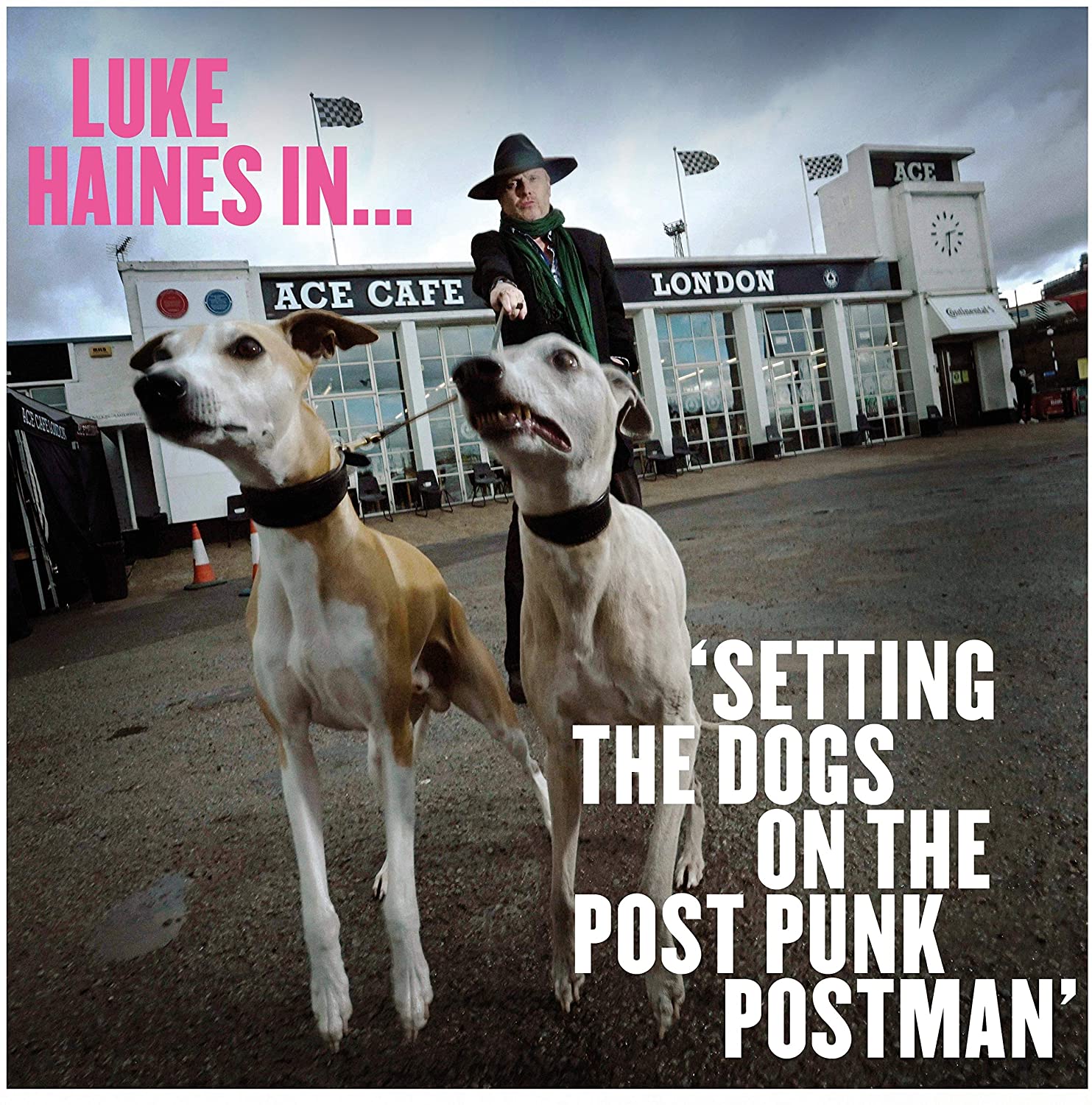

Luke remains as prolific and busy as ever, having recently issued a second collaborative album with R.E.M.’s Peter Buck [All The Kids Are Super Bummed Out] which he toured with Buck earlier this year, but he found the time to sit down with SDE in a north London pub to discuss the Auteurs output and the new box set…

SuperDeluxeEdition: Where did your musical talent come from? Did you learn the guitar in your bedroom as a kid ?

Luke Haines Yeah. I didn’t have musical parents and they didn’t really actively like pop music; they disapproved of it. My mum had me when she was about 30, in 1967, and they were the generation where the ’60s passed them, a little bit. The two pop records they had, apart from stuff like Perry Como and Matt Monro were ‘She Loves You’, the Parlophone single, and ‘Hey Jude’. You wonder what happened in the intervening years…

So when you when you were older and you were at school, what were your ambitions?

To be in a rock and roll band. From about age 13. Ludicrous.

Obvously lots of people have that ambition, but you actually did it.

I wanted to be in a rock band and I wanted to be an artist, because my dad was a graphic designer. He started off through art school and all of that and it sounded really attractive. And when I was young I was quite good at drawing and painting and all of that.

Did you go to art school?

Yes. I was probably the last intake at the free arts school and I did my foundation, like all good rock and rollers do [laughs]. But then I promptly abandoned art for many, many years.

But did you get lots of support from friends and family or did people think you were a bit mad and needed to go out and get a proper job?

Yeah, they thought I was a bit mad…

Did you have a period where you were just doing normal jobs?

No, I’ve never had a proper job in my life. Never. I went to music college after I left art college. I studied music composition, guitar and piano.

That’s quite a surprise, in a way…

You wouldn’t think so… [laughs]

No, not for that reason [laughs] but I just didn’t have you down as someone who went that route of learning properly, how to read music etc.

I liked the sound and the feel of the acoustic guitar but then I got corrupted, quite early on, by electric guitar. My dad bought me a cheap electric guitar. He was quite encouraging. I was doing things that he maybe wanted to do. He didn’t want to play the electric guitar but he liked the creative arts and he was really pleased when The Auteurs had a hit album.

That’s good. He got to see some success.

Yeah. And I bought him a television. I couldn’t afford the house [laughs].

Were you writing songs from an early age? Do you have tapes of songs that might not be the best…

Unfortunately, yes. I was writing bad songs probably from the age of 15.

Were you recording them into a dodgy cassette recorder?

Yeah, in bands we’d do demos. I was good at getting bands together.

Did you do lots of gigging then?

We did gigs, but not lots. It wasn’t like I was on tour or anything.

You didn’t seem to be interested in music technology in any way which comes across from those first Auteurs albums. When people are starting out, especially when they haven’t got a proper band, the normal thing is to get a sampler, synthesiser, drum machine etc.

No. I was before that time. It wasn’t till my mid-20s that I had a Portastudio and that seemed quite technological, for the time.

How hard was it to get a band together? Was that relatively easy thing to do?

For The Servants [Luke played guitar in David Westlake’s late 80s indie band], it was always really hard to keep the band going. You can never keep a drummer, or bass player, for long. They usually go and join Felt. Lawrence even asked me to join Felt – he’s probably forgotten that – but he asked me a long, long time ago. He’ll probably deny it!

In the sleeve notes for this new box set, you are quite lighthearted about how easy it was to get signed and have an album out…

It was! The first Auteurs album was incredibly easy…

But why? Was it just that people recognised the quality of your songwriting?

I think with five years in The Servants I learned what being in a band entailed. I really liked a lot of stuff I was on, the stuff I recorded with Dave – and I still record every so often with Dave, if he asks me, he’s a good friend – but there was a lot of sitting around, not doing very much. We’d record a song in a studio once every three years and put it out 18 months later and then go to Switzerland to promote it a year after that! I decided I was going to give it one more shot. I wrote my best songs, learnt to use a Portastudio, and just got a scratch band together: my girlfriend at the time Alice [Readman], who played in the dying embers of The Servants, learnt to play bass. So there was two of us, that’s good! She thought of the name, and then an old school friend [Glenn Collins] on drums.

What about the cello? Because James Banbury’s cello became almost a signature sound.

He came in after the first album. He recorded on three tracks for the first album, I think, but as a session player. I wanted a cello, [but] I didn’t know I wanted a cello, so I was recording these low backwards sounds on the piano… and the producer said, “I know a cello player” and that’s where he enters [laughs].

The thing that comes across clearly, especially from the 4-track demos which you put at the end of this box set, is that it’s all in your head, the arrangements, and you knew exactly how you wanted it to sound. I’ve been reading this new Paul McCartney book called ‘The McCartney Legacy’ that covers the early Wings years and Paul starts out saying how they are going to be a proper band with equal contributions, but then everyone gets really pissed off with him because he’s telling them exactly how and what to play. How was it in The Auteurs? Was it always obvious that you were the boss?

Yeah… Because that’s what happened in The Servants. David could have very specific ideas about what the lead guitar – i.e. me – should be playing, and at first, I was a bit put out by this, but then I kind of got into it, and I thought “this is good” because he had really good ideas and I enjoy the company of people that are kind of on the same wavelength. Bands don’t have to be democratic.

How did The Auteurs get signed? Did you just take those demos to Hut [the record label]?

No. I was just like phoning up people asking for gigs. On the strength of those demos, they very reluctantly gave me a show; third on the bill. A lot of people who went on to become ‘names’ in the music industry, were very dismissive of those demos… I mean, they were very badly recorded. Then Jon Eydmann, who was at that time the manager of Suede, called up and asked if we wanted to support Suede. They’d heard the demos and simultaneously I’d send tons of them to a label called East West. They sent them all back to me! I’d sent about 20 demos. But they were thinking of signing Suede to a major deal and so they told me Suede had picked up my demo, played it, liked it, and said to their manager “could we get this band to support us?”. This was Jon, who’d seen the live review in the NME and we away. It’s like one of those weird, mad things that you always hope is gonna happen. Suddenly the phone started ringing…

Were you good having to work with ‘suits’ and people in record labels? In your books you’re quite dismissive and jokey about that aspect…

Well, we weren’t The Replacements, put it like that. It wasn’t like a suicide mission from day one. There were things I knew we had to do. But we got really lucky because while all these labels were hovering around, by that point we had a manager who was an alright manager. He fronted the whole of the first album, paid for it all, we’d recorded it all before a label signed us…

That’s interesting. I didn’t know that.

Yeah, yeah, so basically, he just went around the labels with a finished album and said “here you go…”.

If you’re the record label that’s quite attractive because you don’t have to pay for all the sessions, etc.

Yeah, and we kept it very cheap, so we didn’t have to get involved with all that thing of “we’ll put you in a studio” etc.

Does that mean you managed to retain ownership of that first album or did they end up nicking it as part of the deal?

They had it for a time, but I now have ownership. I’ve got ownership of all of The Auteurs stuff, so it worked out all right. I have to say, a lot of this is 50-50 luck and judgement. I wasn’t so super savvy that I engineered it. We got lucky that we had a manager who was a bit of a bastard, but not a bastard enough… inasmuch as he didn’t try and pull anything on us. He didn’t steal anything and we got signed to a label, and they were onside…

This was Hut, who were part of Virgin. They were that thing of a major ‘pretending’ to be an indie…

‘Pretending’ yes. People used to get very het up about that.

Did it have a proper indie ethos?

Yes. David Boyd was the main guy and he came from Rough Trade.

The first album was kind of in tune with the vibe of what was going on at that time, but that was presumably just luck, because it doesn’t sound like you were trying to follow any trends. You’re just doing what you wanted to do.

I mean, arrogantly, I prefer to say that the times got in tune with that album. We recorded it in May/June 1992 so none of that stuff we are slightly associated with really existed at that point, although Suede were around…

You toured quite a bit with Suede. Did you feel a kinship with them or a rivalry?

Not a rivalry, no. A slight kinship… I mean, they helped us out. Big time. They didn’t need to. I mean, I think the fact that we couldn’t possibly blow them off stage, at that point, was probably quite attractive. So we kind of made them look good.

So they didn’t see you as any kind of threat, basically?

No, I wouldn’t have thought so. They had Bernard [Butler]. He was an explosive guitarist at that point. I hadn’t seen anyone who could touch him. And Brett was a great frontman. They had it all. They were super, super tight and we were super, super shambolic. Before we supported them we’d only played about five gigs.

Suede were super tight and we were super shambolic

Luke Haines

Brett had that frontman glamour, where he was thinking back to Bowie, Lou Reed or whoever. Who were the people you were thinking back to?

Jonathan Richman [founder of proto-punk band The Modern Lovers], Mark Smith, Robert Forster.

So a very different kind of thing…

Very different. And the stuff that was being thrown back at us when people started writing about The Auteurs, like the Bowie thing – I mean I love Bowie – but I thought that we had absolutely nothing to do with Hunky Dory. I always thought it was more sort of vaguely somewhere between [The Kinks’] Village Green and early Fall. And Television and stuff like that. And The Modern Lovers.

Going back to your first album, New Wave… So you get signed, the album is basically done. What are your aspirations at this point, because you must have been hoping to have a hit shingle and be quite successful…

No, not at all, not at that time. I remember getting called up a few days after the release and someone said, I can’t remember the exact number, but something like “You’re number 14 in the midweek”. I’m like “what’s a midweek?” I didn’t know what a midweek chart was. I said “So that’s like in the independent charts?” “No, no, that’s that’s the big charts. The main charts”. Wow, okay. How did that happen? I just thought it was cool to have an album out and that we did shows and people came to them.

Did the record company articulate to you what they wanted, what their idea of success may or may not be?

No, not really, which is weird.

Obviously, once you’re signed to a record label there’s a certain element of being on a treadmill, and sometimes you read about bands who can’t get off this treadmill and they lose control of their own destiny. Did you think about that sort of stuff at the time?

I thought about that after the second album [1994’s Now I’m A Cowboy]. I realised that we were on the treadmill. For the first album we were touring and that was good. Because I’d wanted I’d always wanted to be in a band…

And have that lifestyle?

Yes. But then it got… I sort of realised I was finding it hard to write songs and the band weren’t always… erm… in terms of personalities, it wasn’t the romantic vision I had. I’m not sure that really exists…

I’m surprised that you said you found it hard to write songs because you come across as being very prolific. The second album followed quite closely on the first, there was a certain momentum happening.

I should say I was finding it harder to write songs. I wasn’t as as prolific as I am now, but I guess I don’t tour as much. Now, at the grand old age of 55 it’s very easy to write songs. I could write could write an album, tonight on the walk home.

Are you still striving for the perfect pop song?

No, I don’t think in those terms.

You seem to be quite very conceptual…

I’ve come to realise I’m an idiot savant. I think I’m very fearful – no fearful is the wrong word – I’m aware of wasting an idea, perhaps because I don’t want to miss an idea. Not because I think it’s gonna be ‘the song’ or it’s going to solve the problems in the Middle East. It’s just like, this is a nice idea for a song. It’s as simple as that.

That first album [New Wave], got nominated for the Mercury Music Prize and you famously nearly won it. And maybe with a bit more luck, you could have had bigger hit singles. Do either of those things bother you, that you didn’t have a top 40 single or that you didn’t win the Mercury Music Prize?

At the time it did, but again, even with the Mercury Music Prize I didn’t know what it was. For the first year of The Auteurs, even though I’d been in a band for five years, I was quite naive about how things worked. And I was quite bratty as well, because I thought, well, you know, fuck this. I’m a pop musician, I’m a minor pop star. So I’m gonna, eek a lot out of it.

Did you like the music industry? I mean, not all the people working in record labels and PR and stuff are going to be your cup of tea and that is a world that is new to everyone, particularly when they become a signed artist and a successful band.

I think in the early ’90s It was a bit more like the Wild West. I didn’t do anything I didn’t want to do. Although I didn’t really enjoy the videos, I thought it was all a bit… We worked with nice people, so it wasn’t the fault of the directors. But you would come across some really thick people, at points, but a lot of our dealings with the people who were important, were alright. I’d marked myself out as someone who could be a bit bratty, a bit tempestuous, so they tended to be a bit…

Scared of you?

A little bit like that, yeah. Which is kind of all right. It was useful.

Presumably, there was the public Luke Haines who would talk to NME journalists and then a private one, who was different.

Yeah, yeah, of course. I mean, if someone tweets an old interview or something, I never read it, because I don’t want to hear the thoughts of me, aged 25. Would you? But I was smart enough to say interesting, provocative things.

But did that come at a cost? Did you ever pay a price for that?

I don’t know. I don’t know, really. Whilst I was sometimes ‘in character’ somewhat, I still had a very strong idea of what I wanted Auteurs records to be and what I wanted us be and the important thing was always making the records.

So what happened after the first album? The second album had the same producer and the same sound, more or less…

Inevitably, it got a bit more ‘professional’. The reason that I’m sometimes a bit sniffy about the second album, after the fact, is that it did get more professional. We got rid of the original drummer [Glenn Collins], which was partly as a result of a bit of pressure on me and partly – bless him, because he’s still a great friend of mine – partly because he wasn’t cutting it. We got a new drummer who was bit more durable when doing longer shows. The first drummer was great doing 20 minute shows, but would then flag out a bit.

Alice [Readman] learnt the bass. I’m always impressed with people that seemingly learn an instrument relatively quickly and she was pretty good.

She got really good, she had a style and it really worked. [Steve] Albini was really impressed.

What was your vision for that second album? There’s more electric guitars and a few rockier tracks. Did you have any kind of different outlook compared to what you were doing on the first record? I guess there was more money and you could maybe muck around a bit more…

We didn’t muck around. I thought I was trying to hone the songs, make them better and make them kind of broader. I don’t think I had the time to really think it out.

Those first two albums are really the two that are most similar to each other. Even to the extent of the artwork and the whole look of them; they feel like a pair, almost.

Yes, yes, very much so. I mean, in the light of day, now, many many years later – I don’t listen to these albums much, unless I’m doing something like this [the box set] and need to do my homework – but I’m pleasantly surprised. Okay, yeah, it’s kind of ‘part two’, but it rocks more and it sold the most in the US, by quite a lot. It has ‘Lenny Valentino’ on it. That’s one of the few things that the record company made me do, they made me go back and get Lenny Valentino right. So we got it right on the album and it’s a great recording. It’s great record.

The record company made me go back and get Lenny Valentino right. We got it right on the album and it’s a great recording.

Luke Haines

That’s the single where it’s unbelievable that it wasn’t a hit.

It was a bit too early. That was released the same week that Pulp had ‘Lipgloss’ out, just prior to them going really big. They obviously deserved to go big, but I just think that it was a little bit too early. We just missed out by a few places, but the thing is, that song has earned me money over the years. It’s got on many soundtracks.

So after those first two records, do you remember thinking quite specifically about what to do next? You must have been fairly pleased with yourself because…

Not really, no.

Why not?

I thought that, recording-wise, we needed to do something better. I remember being quite fed up with the first album – ludicrously – because I just thought it overshadowed the second album, which is kind of mad. Looking back on the second album now – in a non-career way and just hearing the record – it sounds great. It sounds weird for the time and other worldly… Things like underground movies and all this sort of stuff. People had huge expectations for the second album, chart-wise, but I think it went a couple of places higher than the first album and then the Pulp album at the time [His ‘n’ Hers] I think it went to number one, or something [it actually peaked at number 9. Now I’m A Cowboy peaked at #27, five places lower than New Wave]

So with the third album, After Murder Park, you got in a different producer, Steve Albini, and everything seemed to have a harder edge to it…

It was probably a reaction. Part of it was a reaction against what was going on, which I thought was incredibly lightweight, what is now called ‘Britpop’.

What did you think about Suede and their success, because they were obviously a band that you knew and you would have seen that first record do really well and then they went a bit proggy with Dog Man Star and stuff…

And Bernard left. I don’t really know the album… I know the Head Music album a more because it was a bit more in touch with them, then. I wasn’t really around when they were doing the Coming Up album, but I think their best album is that Sci-Fi Lullabies collection. It’s a fantastic record.

Back to your third record, After Murder Park. Lyrically, you had songs like ‘Back With The Killer Again’, ‘Unsolved Child Murder’… Where was all that coming from?

‘Unsolved Child Murder’ is a true story about a kid in my road who disappeared, when I was about seven and I’m telling that story and the whole thing just started taking a very sort of… I don’t want to use the word ‘dark’, but…

That song was very musical, but you’re not going to have a hit single with that lyric and you would have known that.

I didn’t, I thought in my 20s that anything is viable as a single, thinking with a John Cale, Jonathan Richman kind of mindset. I wasn’t thinking along the lines of Supergrass and ‘Alright’. Supergrass were a good band, but I’d broken my ankle, so I was on a lot of painkillers and I’d spent the year on tour being very untogether and in a very nihilistic state of mind. We hadn’t had a break since the first album and so I went away and wrote those songs and that’s just what came out, this avalanche of… I always get labelled with ‘misanthropy’, and that tends to be from people don’t understand what misanthropy means, but in that case it’s perhaps justified, what happened was a very misanthropic album, a very hard album, came out and it was necessary. It was kind of like ‘let’s clear the decks’…

After Murder Park was a very misanthropic album, a very hard album. It was necessary.

Luke Haines

Did you ever have any concerns about being dropped and having to do something else?

No. I had conviction. I sort of knew that for life, I’m in a rock ‘n’ roll band. I don’t know why I had such confidence in that.

What were the reviews like for that record at the time? Was it well reviewed?

Yeah. It was pretty well reviewed.

How well did it sell?

It sold less, but it still sold, I think. I mean, I think it ended at about number 50. Again, it’s sold quite well in America and we had a good thing in Europe. So it sold enough for us to not be up against it. Someone told me a figure after a few weeks of something like 60,000…

Which compared to today is great

But at the time that was thought of as not a lot. We were in Abbey Road [to record the album] and it didn’t cost much. I think Albini took 10 grand and no royalty or anything. It was 10 grand, plus accommodation, so he stayed in the Abbey Road chateau! We spent ten days in Abbey Road, so the whole thing probably cost less than £40k.

Why did you want to work with producer Steve Albini?

I wanted to work with him on the first album. I mean, things would have turned out a whole lot differently if I’d worked with Albini on the first album. It probably wouldn’t have worked out as well.

What did he bring to the third record?

Attitude. He bolstered my attitude. We became friends; we’re still friends. We were completely on the same wavelength. He got where we were coming from. He got whatever psychic space I was trying to occupy. He made, not concessions, but he took some things from me that he hadn’t done before like recording brass sections and string sections.

What’s interesting about this period is you then recorded the Baader Meinhof album, which is one of my personal favourites…

Me too. After Murder Park had been recorded. The record company liked it! David Boyd was a great A&R man, I remember he said something like “I didn’t sign you to have hit records”, which was like, what the fuck? He said “These are art statements”. I mean, he wanted the records to do as well as they could, but that’s why I never bought into the idea that Hut were some bullshit version of an indie label, because for me they were the perfect version of an indie label. They left me to do things that probably Rough Trade or Mute wouldn’t have done. He was like “You’re the artist. You’ve just got to do what you do”.

I remember buying the Baader Meinhof record at a time and really liking it. I would talk about the album a lot with someone I was working with. He found a book about the Red Army Faction and I became very interested in the whole thing, and understood the lyrics a bit more because of it. How did you become interested enough to want to write songs about it?

I just read a lot, anyway and, at the time, I was drawn to these quite esoteric subject matters. This was before the internet, so you had to go and find the books. I was kind of always into those ideas, not terrorism [laughs] but…

It’s interesting, because it’s pre-9-11 it didn’t have that stigma. And while I didn’t think the characters in the songs were cool, and I didn’t admire the people involved, it was fascinating to understand what would drive people to those acts.

That’s sort of where I was at, with it. Initially I wrote the one song, ‘Baader Meinhof’, probably around the time we were recording After Murder Park and in fact there’s a Baader Meinhof reference in the song ‘Tombstone’. But it could have been on the After Murder Park album and just been a song on that record. But it wasn’t and we had so much time off after recording Murder Park until the release [almost a year between March 1995 and March 1996] so Baader Meinhof got recorded with Phil Vinall, who was the producer of the first two albums and after we did the single [‘Baader Meinhof’] we just stumbled upon this sound. Phil’s friend Kuljit [Bhamra] – who played on the first album – owned a studio in Southhall, so Phil suggested we do it there. We got Kuljit to play on it and once he did, we thought “this sounds brilliant”. It’s just basically acoustic guitar, Kuljit on tons of tablas, mad synth bass and then the most distorted sound I could do. I thought it was a great new sound. I think we added the strings on later, to give it that kind of weird, B-movie feel. We had an Indian percussionist so I wanted Indian-sounding strings. It was just before people started getting interested in Bollywood soundtracks. I just really liked the sound of it and the lyrics seemed to work brilliantly with it, even though they were nothing to do with it. And we just kept on, over weekends for about six months, we just recorded more tracks. And it became this sort of concept. The lyrics became less important, to me it’s more about the sound.

But it was good though. Obviously the album is topped and tailed by ‘Baader Meinhof’ and I don’t know whether it’s a perfect narrative or not, but you feel like you’re following the plot.

I’m not trying to cop out of the lyrical aspect – I wholly stand by it, I think it’s a good idea – but I wasn’t trying to make any kind of political statement. I think what I was trying to do was make the music sound really cool. Like a pop record!

You could have made Baader Meinhof another Auteurs album, in theory, so why make it a side-project with the band name the same as the album title? You must have known that that would make it harder to find, harder to categorise…

Not really. Again, I hadn’t really thought about those terms. I just thought this is another record and it goes somewhere different.

And the record label were supportive?

I was amazed that they were gonna put it out. They gave me an advance for it, afterwards.

That’s like living the dream. You can write about anything, do anything and people were paying you to do it and releasing the albums.

It seems like it now, but in the 90s it was almost like a day-to-day [occurance]. I didn’t think it was that strange, which might be delusional on my part, but it just seemed like ‘this is the next record’, and we’re doing it. It wasn’t something I fretted about. I didn’t think “I’ve done this and I’m going to get dropped”

Were you pleased to be making a living out of being in a band, being an artist, recording music, and releasing it. Were you satisfied with that?

No [pause]. I still hadn’t made [the album I wanted to make]… although I’d say Baader Meinhof comes close – I think it’s one of the best records I’ve made. But at the time, I thought, I’ve got to do more like this. It’s was actually really hard to get out of the mindset of that sound, because I just thought that was a great sound.

Okay, but that’s an artistic aspiration. What I’m talking about is dreaming of owning a mansion, driving a flash car, having the triple platinum album where you never have to work again for the rest of your life, which I know is a clichéd rock star aspiration. That doesn’t sound like that was something that interested you.

Not really. I mean, when we were doing the Black Box Recorder album The Facts of Life, and we had a hit single and went on Top of the Pops; I felt a bit disillusioned.

What, like you’d blotted your copy book by being in the charts? [laughs]

A little bit, a little bit. But I’m not looking down on pop. Pop’s great.

Putting the whole Britpop thing to one side, the interesting thing about that period in the mid 90s is a lot your contemporaries, or however you want to describe them – like Suede, or Pulp or whoever – they had a moment in the sun where they had a big crossover-type record. And you didn’t really have that, which doesn’t sound to me like it really bothers you that much.

Not in retrospect…

But at the time, did you ever think, ‘it’s not fair..’?

I thought that when ‘Lenny Valentino’ missed the charts by one place [it peaked at #41]. Even if it had been 39…

…You could have gone on Top of the Pops.

No, the thing is, I refused to do Top of the Pops, like an idiot. With ‘Lenny Valentino’, I think in the midweek it was like #30 or something. “Do you want to be on Top of the Pops?” “No!” [laughs].

Do you regret that?

I don’t regret it, no. I don’t think it would have made an ounce of difference to what happened afterwards if ‘Lenny Valentino’ had got to #32. There wasn’t really another big hit single on the album, anyway.

The last Auteurs album was How I Learned to Love the Bootboys, which came out in 1999. So you had After Murder Park, Baader Meinhof, and then England Made Me, the first Black Box Recorder album in ’98. Were you getting bored of the construct of The Auteurs as a band?

Yeah. I felt after After Murder Park we were kind of done. We’d already started what became the Boot Boys album during the Baader Meinhof sessions. 1996 to 1999 is rather like a blur of recording. The dates are always a bit scrambled, because a lot was going on. The Boot Boys sessions were a bit more efficient and they were in bigger studios. That’s the point where Hut were starting to say “can you have a hit, please?”. So eventually I kind of got it together. We went to another label for Black Box Recorder. David [Boyd] was fine about that; an amazing A&R man. The first BBR album came out and was a critical success. Again, it’s one of my favourite albums, and again we kind of found a sound for it. So the last Auteurs album was recorded concurrently. And at the time I thought it kind of suffered a bit because of that… but listening back, it sounds okay.

You were on a role with Baader Meinhof, England Made Me and How I Learned to Love the Bootboys, but it wasn’t perceived like that by many people because it was effectively three different acts.

I think journalists really had a hard on for the next Black Box Recorder album. The Auteurs were seen as the old thing. It’s 1999, it’s the fourth album, there’s no hits on it. But for many years, I’ve always thought that’s a much better record than I ever gave it credit for

So that was the last Auteurs album. Obviously you made the Das Capital album.

I got called in, which was very rare – me and my then manager. And we had the meeting with David Boyd. Back in 1992 the Hut office was this very cool place, on top of the old Virgin building in Kensal Rise. Everyone smoked spliffs, Dave’s hair was really long and he looked like he was in the Grateful Dead. It was great. And as the years went by the the office gradually moved down the building and by the time we got to the Das Capital album it was at the front door [laughs]. Anyway, we had this meeting and Dave had this bit of paper which he showed to us and on it was just a few words: “Auteurs contract to be terminated” [laughs]. And then he said “I don’t want to do this” and he screwed it up and threw it in the bin and said “I’ve got an idea. We’ll do a greatest hits album and just record the songs again”. We were for the chop, so it was a case of let’s get as much money out of the bastards as we can. So you could look upon it as a contractual obligation album, but it was done in the best spirits of like “fuck the company”. I hadn’t listened to that album in ages, but it was the first one I played for the box set and it sounds good. I wasn’t sure at that point what I was going to do, so I wrote a couple of new songs. We had great fun. I just re-recorded not the best songs but the songs that would work well with that treatment.

Thanks to Luke Haines who was talking to Paul Sinclair for SDE. The Auteurs box set, People ‘Round Here Don’t Like To Talk About It: The Complete EMI Recordings, is out now via Cherry Red.

Compare prices and pre-order

THE AUTEURS

People Round Here Dont Like To Talk About It - 6CD box set

Tracklisting

People ‘Round Here Don’t Like To Talk About It The Auteurs /

-

-

CD 2: New Wave

- Showgirl

- Bailed Out

- American Guitars

- Junk Shop Clothes

- Don’t Trust The Stars

- Starstruck

- How Could I Be Wrong

- Housebreaker

- Valet Parking

- Idiot Brother

- Early Years

- Home Again

B-Sides

- Subculture (They Can’t Find Him)

- She Might Take A Train

- Glad To Be Gobe

- Staying Power

- Wedding Day

- High Diving Horses

Bonus Tracks

- Housebeaker (Rough Trade Singles Club)

- Valet Parking (Rough Trade Singles Club)

- Starstruck (Acoustic)

- Junk Shop Clothes (Acoustic)

- Housebreaker (Acoustic)

- Home Again (Acoustic)

-

CD 2: Now I’m A Cowboy

- Lenny Valentino

- Brainchild

- I´m A Rich Man´s Toy

- New French Girlfriend

- The Upper Classes

- Chinese Bakery

- A Sister Like You

- Underground Movies

- Life Classes / Life Model

- Modern History

- Daughter Of A Child

B-Sides

- Lenny Valentino (Single Version)

- Vacant Lot

- Car Crazy

- Disney World

- Lenny Valentino (Original Mix)

- Underground Movies (Alternative Mix)

- Brainchild (Original Version)

Bonus Tracks

- Government Bookstore

- Everything You Say Will Destroy You

- Chinese Bakery (Acoustic)

- Modern History (Acoustic)

-

CD 3: After Murder Park

- Light Aircraft On Fire

- Child Brides

- Land Lovers

- New Brat In Town

- Everything You Say Will Destroy You

- Unsolved Child Murder

- Married To A Lazy Lover 8 Buddha

- Tombstone

- Fear Of Flying

- Dead Sea Navigators

- After Murder Park

Bonus Material B-sides And Rarities

- Back With The Killer Again (A Side)

- Kenneth Anger´s Bad Dream

- Former Fan

- Light Aircraft On Fire (Single Version)

- Car Crash

- Buddha (4 Track Band Demo)

- X-Boogie Man

- Everything You Say (Early Steve Albini Recording)

- Tombstone (Alternate Recording)

- Unsolved Child Murder (Early Version)

-

CD 4: Baader Meinhof / Baader Meinhof

- Baader Meinhof

- Meet Me At The Airport

- There’s Gonna Be An Accident

- Mogadishu

- Theme From “Burn Warehouse Burn”

- GSG – 29

- …It’s A Moral Issue

- Back On The Farm

- Kill Ramirez

- Baader Meinhof (Alternative Version)

Bonus Tracks

- I’ve Been A Fool For You

- Baader Meinhof (Confrontation Remix)

- There’s Gonna Be An Accident (Fuse Remix)

- There’s Gonna Be An Accident (Muziq Remix)

- Mogadishu (Dalai Lama Remix)

-

CD 5: How I Learned to Love The Bootboys

- The Rubettes

- 1967

- How I Learned To Love The Bootboys

- Your Gang, Our Gang

- Some Changes

- School

- Johnny And The Hurricanes

- The South Will Rise Again

- Asti Spumante

- Sick Of Hari Krisna

- Lights Out

- Future Generation

Bonus Material B-sides And Rarities

- Get Wrecked At Home

- Breaking Up

- Politic

- ESP Kids

- Johnny And The Hurricanes (Alternate Recording)

- Future Generation (Alternate Recording)

- School (Alternate Recording)

- Essex Bootboys

- The Rubettes (Acoustic Version)

- 1967 (Acoustic Version)

- Some Changes (Acoustic Version)

- Lights Out (Acoustic Version)

-

CD 6: Luke Haines & The Auteurs / Das Capital

- Das Capital Overture

- How Could I Be Wrong

- Showgirl

- Baader Meinhof

- Lenny Valentino

- Starstruck

- Satan Wants Me

- Unsolved Child Murder

- Junk Shop Clothes

- The Mitford Sisters

- Bugger Bognor

- Future Generation

Bonus Tracks

- Bailed Out (4 Track Demo)

- American Guitars (4 Track Demo)

- Showgirl (4 Track Demo)

- Glad To Be Gone (4 Track Demo)

- Starstruck (4 Track Demo)

- Early Years (4 Track Demo)

-

CD 2: New Wave

Interview

Interview

By Paul Sinclair

12