Wings drummer Denny Seiwell on Macca’s Ram and the ‘Ram On’ anniversary tribute

Denny on his love for Ram and why he left Wings

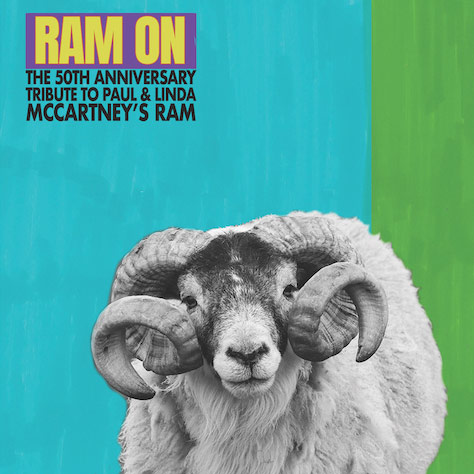

As recently reported on SDE musician and passionate Paul McCartney fan Fernando Perdomo has masterminded what has turned out to be a fabulous tribute version of Paul and Linda McCartney’s 1971 album Ram. The album is covered in its entirety and features various guest vocalists and musicians with a core team consistent across all the tracks. One of those is the original drummer on the Ram album – and subsequent Wings drummer – Denny Seiwell! SDE caught up with Denny recently and he tells us about the Ram On project, his time in the Paul’s band and the Wings reunion that Paul seriously considered…

How did you get involved in the Ram On project? Did Fernando Perdomo contact you directly?

I met him at a show, five or six years ago and then I keep bumping into him and he was really a sweet guy. Then Denny Laine asked me to come down and just sit in and play with him, and I said “sure, I’ll do that”. Fernando was there and we started talking. He says: “I recorded ‘Too Many People’ and ‘Some People Never Know’ in my home studio. I finished the tracks but I didn’t put drums on them. Would you mind coming up and playing drums?” I said “Yeah, what the hell”. I thought, “let me see if this kid’s good or not”, you know. So I went up and I was blown away. It took me all of ten minutes to do two songs, you know.

We remained friends, and about a year later, he called me up and he said “Do you know it’s 50th anniversary of Ram? Let’s do the whole album!”. I said, “Well, yeah, I think so, but before we do anything let me call Paul, let me see how he feels about that”. So I called Paul and he said “Yeah, go ahead, have fun”. So it seemed we got his blessing and then I talked to his people at MPL [McCartney Productions Limited] in New York to make sure that we didn’t, you know, crush anything that he was planning and that [there were] no conflicts of interest.

What do you think makes the Ram album so special?

I know what was really so special about it: Linda put a foot up his arse and said “You get up, we’re going to New York, we’re going to make a record, you can’t just sit up here at the farm in Scotland…”. It was that Beatle break-up that was causing all the angst in him. I just think that some emotional part of his life was coming out in Ram and in the music.

What were your preconceptions, because at that point in time McCartney, that first solo album was the only non-Beatles music from Paul that people really would have heard. There must have been an element where you didn’t really know what it was going to be like, the music that he was making?

Sure, I had no idea what it was going to be like. But as New York session players, that’s what we expected. Every day when we went to work it was a clean slate, you didn’t know what you were going to be doing. They are paying you handsomely and they expect you to do the job, do it quick and do it great! So I mean, when we started hearing the material we were saying “Oh my God, this is not another typical album that we’re going to do, this is going to be very important in the history of music”. So we gave it our best, I must say, and Paul gave us a clean slate to do anything that we wanted – and he hired me for me, he didn’t hire me because he wanted to tell a drummer what to play. He only asked me to change one part that I came up with on Uncle Albert and that was the only time – even in Wings, he never [did].

But to be honest, I like the way Paul plays on the McCartney album, he’s a really interesting drummer. So when I did the audition, I kind of went in to how he or how Ringo would play it. So when I’m hearing the song for the first time on the Ram album, I’m thinking “Well how would Paul play it if he was drumming it?”

Paul is a master when it comes to the multi-part song with different sections – particularly on the Ram album – so there’s quite often different tempos, different feels going on within three or four minutes aren’t there? Does that make it particularly gratifying for a drummer?

Yeah, yeah, yeah. In the past I used to do shows up in the Poconos mountains and the Catskills where you’d have a dance team and a comedian and the dance team would have this music that went all over the place. So I was well versed in that, and like ‘Uncle Albert’ that was done in one pass, that wasn’t broken up in ‘Uncle Albert’ and then ‘Admiral Halsey’ later. Same with ‘Back Seat’ and a lot of those tracks… ‘Little Lamb Dragonfly’, ‘Get on the Right Thing’, all of those songs were done as one take even though they had several tempos, we just learned them, remembered them. Paul would set the tempo on whatever instrument he was playing.

How did those songs sound in the studio at the time? Because my understanding is that Paul did all the bass overdubs later on?

Correct. There was only three of us, Paul playing either guitar or piano, and he’d sing a guide vocal. [David] Spinozza or Hugh McCracken, one at a time, were the guitar players, and me. So he based all of his bass parts off of my bass drum beats that I came up with. So the fact that I saw this as a way we’re going to work and I knew I had to really be careful on the parts that I came up with because it’s going to influence the way Paul comes up with his bass parts. And he loved working like that. So yeah, I’ve never heard any of the tracks. When the record was over he sent me a little box of the Ram album and my doorman said “Here is a box of records that are here for you”. I went up and I put it on the turntable and I was just blown away to hear the whole thing, you know, it was pretty amazing.

And tell me the story about your drum kit – I was blown away by this story of how, you know, the drum kit was a Beatles drum kit. Tell me that story!

I don’t know if it’s [true] Ringo says it isn’t, but I think it is. This place in New York is going out of business and they had a Ringo or a Beatles display I guess, and they had a Ringo Starr drum kit in there, a black Ludwig kit. And they said it was taken from the Shea Stadium concert in New York and that’s how they got it. And so they had this auction and my buddy who runs a drum shop in New York, he called me up, he said “Hey, I’m going to this auction, they have the Beatles drum set from Shea Stadium. I’m going to go get on it, I don’t really want all of the drums, I just want the snare drum, would you be into”? I said “Sure, I’d love to have it, but it’s probably way above my head, financially”. So he goes to the auction, he calls me up, he says “I got it, I got the kit and you can have the two tom toms and the bass drum”. I said, “Okay, how much?” “300 bucks”, I went “Oh my God”. So I ran down there and I gave him 300 bucks.

So Paul calls me, between the audition and the first session, he calls me up and says, “I’d like to hire you for this Ram album”. So I show up on the date and I had my drums in the drum booth. Paul comes in, he goes “Hey man, you ready to go and then he looks and does a double-take on The Beatles drums. I used them, with my dad’s snare drum for the whole album.

That’s pretty amazing. So the bass drum had ‘The Beatles’ written in it?

Of course, yeah. I sold the drums back to the guy because they weren’t great; I could make them sound good but they weren’t an overall great sound, but I kept the head. And then I heard that one of those original seven heads went for $2 million over here. And I started looking for it, I couldn’t find it.

When people cover records, quite often the mindset is, “we have to do something different” because they think there’s no point like trying to replicate it perfectly. But Fernando has just spun that on its head to a certain degree, because all those parts are replicated in quite a lot of detail. Did that surprise you?

Well no, that was my role. You know, we figured having the original drummer and playing the original drum parts – that’s a basis that you can’t go wrong with. And Fernando was very fussy with a lot of the guitar parts, he’s really great at that. Getting the same sounds and the same parts and you know adding a little bit of our own thing, without taking away from the original spirit of Ram. And really the hardest part was saying no to some great vocals. He would bring in three or four people to sing the same thing and then we’d go through it and I’d choose one, not for namesake, who might sell more records… none of that. It was like who has the spirit of the record? I don’t care how much they sound like Paul – although I’d like it to have that delivery and cadence that Paul had. So I would say “Yay or nay” on a lot of the important vocals and that was my role.

Even though there are different vocalists for each song, the album has a consistent tone and feel, doesn’t it?

Yeah. Between the two of us I think we did an exemplary job, especially going through lockdown. He would make a mix and send me a rough or three or four different roughs and he would say “What do you think?” And we’d talk about it and we would pick the best one or sometimes we would ask people to redo something, make it a little bit different… It really came out well, I’m very proud of it.

One of the things that comes across to me is how Paul’s vocal range at that time, was immense. His vocal talents were off-the-scale really. And I think for any singer to try and match his range, it’s going to be a challenge isn’t it?

Yeah, absolutely. You couldn’t replace his vocal. I mean this record [Ram On] is really good but ah, the vocals are great but there’s not a Paul McCartney. But I’m telling you when we found Timmy Sean to do the vocal on ‘Monkberry Moon Delight’ and Dan Rothchild [‘Too Many People’], and some of the other people, like Adrian Bourgeois [‘Dear Boy’] it just blew me away.

Linda aside, you’re the only person in Wings that worked with Paul, before becoming a member of Wings.

Yeah.

So to a certain extent you knew what you were letting yourself in for. When Paul said “Would you like to join my band?” You’d had that experience of working with him in the studio. You could compare and contrast the two things: being a session musician; working with him in the studio and then being a member of his band. How did those two things compare?

I wasn’t a member of his band. This is the way he went at the time. So first of all he called me up for a vacation and said “You and your wife come on over and we’ll hang out a little bit at the farm”. And he brought – Hugh McCracken was over as well and he was finishing a tour with Gary Wright. So Paul said “You know, I miss my old band, I’m thinking about putting a band together, shall we put a band together?” And I go “I’m in”.

And Hugh said, “I can’t”. He didn’t tell them why but over time I found out that he had a previous marriage and he had young kids. When I told Paul this, just a couple of years before Hugh had passed away, it really made all the difference in the world. So [anyway], I went home, I went back to New York and Paul said “Okay I’m bringing Denny Laine over, let’s come over and form a band”. It wasn’t “Paul McCartney and Wings”. He wanted the band to be known as “Wings”.

And after we brought Henry [McCullough] in and we went on the road and we did the University tour, the European tour and then the British tour, we had really become a band, band, band. It was a different head from being a session guy and I enjoyed that. It was a different way of thinking about the music.

Why did you say yes? I know if Paul McCartney asks you to work with him, it’s probably hard to say no, but weren’t you enjoying life in New York as a session musician? Why did you want to be in a band?

I’m sorry, sometimes you have a great time in the studio and the other times you go to work and you’re polishing a turd, you know. I mean, sometimes the stuff you are asked to do isn’t that great.

I was grateful that I was called on so many times. I was making good money but the difference between Paul McCartney and just doing an ordinary session man job… there is no comparison. Paul was the musical genius of the time, you know, and I respected everything about him. And I never met anybody with that much talent and we hit it off so perfectly. That’s why he said “Are you interested?” I said “Hell, yeah, count me in”. And we were going to go with Hugh McCracken and Paul Harris, we were thinking about this anyway. Paul Harris on piano – there was no talk of Linda yet.

After Hugh had left and went back to the States and I came home to New York, he called me up and he says, “Yeah, I think I’m going to have Linda play piano”. That was a bit of a shock, I must say, because she doesn’t play piano. But he says “You know, the stuff that I need a piano player to do, I can teach anybody to do and I’ll make sure that she can do her part and I’ll find simple parts that really work for the songs”. And I trusted him so much musically that I went “Great, whatever, that’s fine”.

But did your relationship change from when you were together working on Ram to when you were in Wings?

Exactly the same. Paul and I could just look at each other without saying anything, we had communication, you know. And Linda was doing her best, you know, God bless her, she really did her best. He would teach her nice simple parts and you know, at the end she had really advanced her skills on a piano and her singing as well. She became a very integral voice of the Wings sound.

When Ram came out originally, it received mixed reviews, didn’t it? Paul must have been disappointed about that. Did he ever talk to you about it?

Yeah, we were all a little disappointed but, you know, I believe it was just jealous people, complaining about him breaking up the Beatles… talking out their butt holes, you know. I really think that they weren’t listening to the music or they wouldn’t have missed that much great music, you know. And you’ve got to remember if our critic, if he writes [that] everything’s good, he’s going to be out of work in no time at all. A critic needs to find something wrong and write about it.

I’m sure Paul hated me for many years

Denny seiwell

What about that university tour? It’s exactly what he was talking to John Lennon about when they were doing Let It Be in early 1969: getting back-to-basics and going out on a small tour. Paul obviously got a big kick out of that university tour, but was everyone else enjoying it as much as he was?

Oh my God, yeah, it was the most fun we ever had as a band. I don’t think any of these iterations of Wings after this one had the kind of fun we did because we were really breaking the ice and we had a 12-passenger Transit van, wives, kids and dogs, and a little truck with our gear in it, two roadies, and we just set out not knowing where we’re going. We’d stop at a university and say “Can we play here tonight?”. It was the best, right. At the end of the night we’d sit with the kids with a money box and we’d pass it, one for you, one for you, one for you, you know these pound notes. I think it cost 50 or 75p to get in the show. It was great.

With the Wild Life album there wasn’t that layered complexity that there was with Ram. Did that surprise you or were you expecting it because you were a new band?

When we, when I came back to Scotland, after I went home for two weeks or so, Paul called and he said “Okay, I got Denny here, come on back over and we’ll start learning some songs”. He had written a bunch of songs. So when we were in recording Wild Life, five of the eight songs were first takes.

And a song like Mumbo you can hear it – “Take it Tony!” – you know, we were doing a jam and Paul looks up at the engineer and the red light’s not on, and it’s like “Take it Tony!” [laughs] and he hit the button and that’s where you hear the machine start. Most of that material – it’s only eight songs – that was developed up at the farm in Scotland.

When we got down to Abbey Road and we started recording that stuff, they wanted to do a cover of ‘Love is Strange’ and somebody said, “Well why don’t we do it reggae style?” And so we started fooling around and it was all very impromptu and that record was done in a weekend. The tracks were done in a couple of days, if that long, and then we started doing some overdubs and then we actually took a little time to mix it and make sure that everything sounded good. When we were mixing, sometimes we would be in the studio until four in the morning and you had a ‘fader assignment’, that meant you had to raise or lower some faders [at the appropriate time] and if you blew your assignment, you had to do it again, so it was a band effort, it really was a band effort.

Tell me about that European tour [Wings Over Europe] with the open-top double-decker bus. Now that bus looks crazy. Was it as much fun to be on that bus as it looked from the pictures?

Not really [laughs]. You know, it only went 35 miles an hour. A lot of times, if you had a couple of hundred of miles between cities, we’d be on the motorway and they’d have to send cars from the other end, like they sent like five lime green BMWs for us, brand new BMWs – the bus stopped and we hopped into them, otherwise we never would have never made it in time for the gig. It wasn’t comfortable. It had the mattresses on the top deck so if the weather was fine you could go up there and lay on a mattress. In the South of France it was great but Germany, not that great! [laughs].

But isn’t that an example of like Paul coming up with a sort of crazy idea that sounds fun but in reality isn’t that much fun?

But it was fun, it was great fun. We bonded in that time period. Those two weeks, 11, 12 days, whatever it was, we really bonded as a band. And actually we got better, as the gigs went on, and the band sounded better and we were more comfortable with each other performing live, it was a win/win.

You ended up playing on three albums, including Red Rose Speedway. How did you feel about the progression, in terms of the musicality?

Definitely, the progression was obvious. It still wasn’t up to Ram, but it wasn’t meant to be because it was a band. Even though it was a band, it was still all Paul’s music and every once in a while he let Denny Laine throw something in or he let Henry throw something in. But basically, he was the songwriter in Wings. But the progression was very obvious, it was moving along nicely, you know. And by the time we were doing Band on the Run in Scotland, I mean we had truly become a band. I mean, we had the British tour right before that, and we gelled as a band and it was a good, as Paul used to call it, “A shit-hot rock and roll band”. And so we had all of that other element too, you know, but we could go from ‘Mary Had a Little Lamb’ to ‘Give Ireland Back to the Irish’ to ‘1882’ or ‘Wild Life’. There were so many different styles which is what really made it interesting.

Obviously, you left before Paul went off to Lagos to do Band on the Run, but you were like playing and rehearsing that material in Scotland beforehand?

Yeah. The story… I mean that’s the ugly part but Paul was really adamant about Henry playing a couple of parts the same way every time we performed that song and especially if we’re playing live. Henry is too organic and he was pushed into a corner one day and he said “Oh, fuck you!” and he left. And there were some other problems with the Beatle lawsuit and everything and we weren’t making any money, we were promised all this money that never happened. It was difficult, I must say in all honesty, it was difficult to live with the retainer salary that we were paid.

There was no management, no office, no anything… We were kind of our own and it was a trust thing with Paul and it was all done on a friendship and a hippy handshake, you know. So no contracts or no anything and after a while it wears on you that you’re one of the biggest bands in the world and you’ve got nothing to show for it. And life is actually tough, paying bills and stuff like that when Paul is driving around in brand new Lamborghini’s and buying, you know…

Paul always rolls out the story about how the night before they were due to fly off to Lagos, you left the band. But I imagine that isn’t quite how it panned out.

Yeah, that’s the way it happened. I’m hearing another bad piece of information from one of the members about… well, it was Denny Laine, you know. Henry had already gone and I was trying to convince Paul to postpone recording in Lagos for a month and bring in a new guitar player and get him up to speed so we can go down there and record it the way we rehearsed it in Scotland – as a band. There is a two track of that rehearsal somewhere in the universe. Man, it’s better than the real album because it had that band vibe again; it was really great. I’d pay anything to hear that again.

But Paul played all of those parts on the record when he went down there [to Lagos] but I said “Get a guitar player”, he said “No, we’ve just got to do this, we’re going to go down and [we’ll] do it. We’ll fix it with overdubs” and I went “Not again, man… we just spent three years becoming a band”. So I’m thinking about that, I hear some more information about the financial end of the situation and I said “You know what, I think it’s time for me to leave”, and I called them up, with a car in front of my place, because I just… I can’t do this anymore. I would have loved to go to Africa, I’m not afraid of going to Africa for Christ’s sakes but I wasn’t going to make another record without an agreement in writing as to what my royalties would be. You know, I’d given enough, you can give so much and then it’s time to pull the plug on it.

Were you calling his bluff to some degree? Did you expect him to sort something out?

That’s my biggest regret that I didn’t sit him down before I did that. It was just like the straw that broke the camel’s back, you know. I heard another bad piece of information but we lived as a family, we travelled as a family, we loved as a family, you know, it’s like hippies, just really all in. And except for this one little thing – and I’d just heard another piece about this one little thing [that gets] bigger and bigger and bigger – and I just said “You know what, I don’t think this is going to be in my best interest to stay”.

It broke my heart, it broke my heart and it’s something that I’ve regretted ever since I did it and I’m so happy that over time Paul and I became friends [again] because I’m sure he hated me for many years but we became friends around 1994 when he played here at the Anaheim Stadium. I said to my wife, I said “Let’s just drive down and see if we can get in”, you know, say hello or something like that.

So we drove backstage and I see a security guy in a golf cart and I said “Hey man, would you just go in and tell Paul that his old drummer Denny and his wife are out back here”. He runs in on his golf cart and he comes out 30 seconds later and he said “Hop on”, and took us right into Paul and Linda’s dressing room and Paul and Linda were there and the kids were there and my wife used to babysit the kids, she went on tour with us, you know. So it was a family reunion, it was great and Linda slipped me the phone numbers so we could stay in touch. She said “We miss you guys, we love you”. And the hurt was over and we became friends again and I helped him with, you know, some stuff like Wingspan and different things that he was doing.

What did you make of the Band on the Run album in the end? Did it surprise you that it became so big? You must have been aware of how good the songs were, I guess, if you had been rehearsing it?

Well I don’t know, it wasn’t my favourite. ‘Jet’ was okay but ‘Band on the Run’ [Denny sings the chorus], I don’t know, just, you know, not what we were going for and it wasn’t my favourite but his music is always like that though. You have to hear it a few times until it sinks in and then you never forget it. But yeah, I made a big mistake there and that’s one of my only regrets in life.

It’s interesting you said that there were some recordings made, because famously Paul had some demos with him, didn’t he, when he went to Africa which –

Yeah, I heard that he had a couple of cassettes just to go down there with, so they had a reference from the original rehearsals, and they were stolen. I’m pretty sure it was a two-track, a Studer two-track running up there in the barn [in Scotland] when we rehearsed and that’s what those cassettes were taken from.

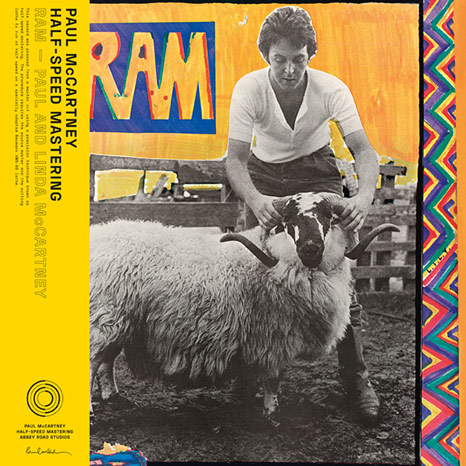

They would be amazing to hear, because when Paul issued the Band on the Run deluxe edition, in 2010, they were not included. Getting back to Ram, where do you think it stands in Paul McCartney’s post-Beatles era? Would you put it at the very top?

Yeah. Oh yeah. The more people that I run into, everybody says “Ram was my favourite record”, period, not just my favourite McCartney solo album, they say “My favourite record”.

You Might Like

Do you think Paul understands what makes that record so great? Because my theory with Paul McCartney is that it almost seems like luck if something is brilliant or if something is not so good – it’s just whatever phase he’s in, whatever mood he is going in. He’s never really, recreated Ram again has he?

I think it was all the feelings during that Beatle break-up that inspired that whole record. And I believe that’s what made it so special.

Is there any chance of this ‘Ram On’ band ever playing live? Have you guys been talking about doing that as we come out of lockdown and COVID?

Yes, we’re talking about that already. Fernando is just back from a trip to Miami and I believe in the next week or two we’re going to call the guys that live in LA and get together and see if we can come up with something that does justice to the album

An attempt being made and I would be all in for that, we could just – you know, the key cities: New York, Chicago, LA or San Francisco… maybe even go to England.

You must be proud of the finished Ram On album because I’ve enjoyed listening to it so much and it really does evoke the spirit of the original doesn’t it?

Yes, thank you. I mean, I know you’ve got ears, you’re not one of those guys who listens with their eyes. I can tell from the questions you’re asking me that you know what it is and you’ve spent some time listening to the music and we are proud of it, I am very proud of it. You know, and Fernando is talking about doing another cover of the Wild Life album. I don’t care what the critics say, I like it!

I’m hoping that Ram On comes out on vinyl at some point as well.

Well they’re talking about that. If it reaches a certain sales point that we’ll start manufacturing the vinyl. But also there’s a lot of music on it – you can only put 20 minutes on a side with vinyl. So we’re trying to figure out but they’re trying to get it ready for Christmas if it can happen, it will happen.

You’d probably have to leave off the extra tracks at the end, Another Day and the B side and all that stuff…

Yeah. Well if it’s up to me I’d leave off the two ‘Ram On’s because that was just Paul screwing around one day in the studio and he had a floor tom tom, a foot stomp, a ukulele, and he was making radio commercials for the album. That’s what ‘Ram On’ was. So I don’t know if that needs to be on there but I like having ‘Another Day’ and ‘Oh Woman, Oh Why’ included.

Yeah, but Denny, you can’t leave off proper album tracks, there would be an outrage if you did that!

Yeah, that is true [laughs]

Let me ask you one more thing before we go. I don’t know how sentimental Paul is, and we’re all getting older, but do you think, he would ever want to get together with you guys: you, Denny Laine etc. and maybe do something as a nod to the old days or do you think we are past that?

I went to see him right after Linda died, my wife and I went over. We were hanging out and I said “Why don’t we do like a Wings reunion thing for Linda’s food company or some charity or something?” He said “Yeah, it’s a good idea”. And then he said “Get together with some of the guys and see who’s interested”. So I started doing that, I came back and I called him up and said “Everybody’s interested, do you want to do it?” And he goes “Well I’ve been thinking about it and having a Wings reunion without Linda would be having a Beatles reunion without John”. So that was nixed.

Did you ever hear Paul’s reworking of ‘Heart of the Country’? You mentioned Linda and her food company. There was an advert for Linda McCartney’s vegetarian food about seven years ago, and Paul rerecorded the song in a slightly sort of ‘busker’ fashion.

I never heard that. There’s a lot that I missed of what Paul’s done over the years. I have my own life and I was doing all kinds of recording a lot of movie soundtracks, TV shows and what have you, I just went back to the session world and it’s just now, when I was 75, I got signed my first record deal. I had my first deal as an artist and I have a jazz trio.

Thanks to Denny Seiwell who was talking to Paul Sinclair for SDE. Ram On: The 50th anniversary Tribute to Paul and Linda McCartney’s Ram is out now on CD. Vinyl may follow later this year.

Compare prices and pre-order

Fenando Perdomo & Denny Seiwell

Ram On - CD

Tracklisting

Ram On Various Artists / Features Fernando Perdomo, Denny Seiwell, David Spinozza et al

-

-

CD

- Too Many People feat Dan Rothchild

- 3 Legs feat The Dirty Diamond and Durga McBroom

- Ram On feat Pat Sansone

- Dear Boy feat Adrian Bourgeois

- Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey feat Bebopalula

- Smile Away feat Timmy Sean

- Heart of the Country feat Dan Rothchild

- Monkberry Moon Delight feat Timmy Sean

- Eat At Home feat Dead Rock West

- Long Haired Lady feat Rob Bonfiglio and Carnie Wilson

- Ram On Reprise feat Pat Sansone

- Backseat of My Car feat Brentley Gore

- Another Day feat Gordon Michaels

- Oh Woman Oh Why feat Eric Dover and Lauren Leigh

- Too Many People (Slight Return)

-

CD

Interview

Interview

Reviews

Reviews

By Paul Sinclair

23