Arthur Baker on remixing in the 1980s

The legendary remixer/producer tells all!

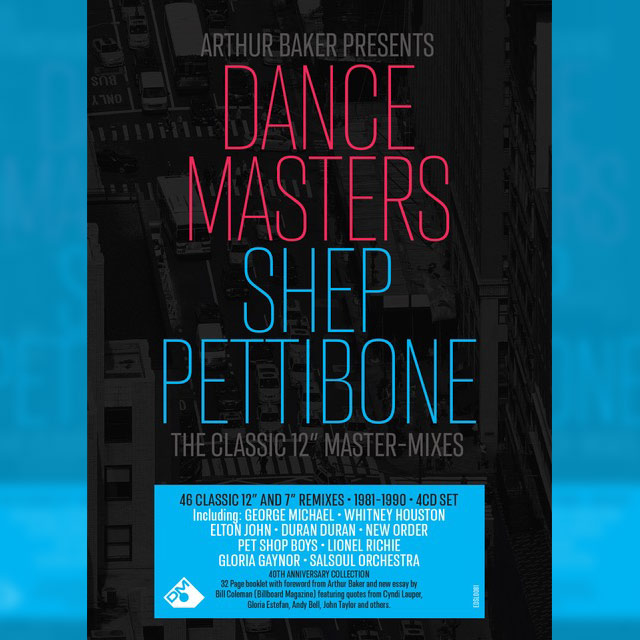

On the eve of the release of the new remix compilation Arthur Baker presents Dance Masters: Shep Pettibone, SDE talks to Baker about this new remix series and takes him back to the Eighties. In a candid and entertaining discussion, the legendary remixer and producer talks about the logistics of remixing, sharing studio space with Shep Pettibone, Bruce Springsteen watching him at work, how much he’d get paid for the big name jobs and whose job it was to buy the drugs…

SDE: Arthur, you’re curating this new series called Dance Masters for Demon Music. There’s going to be a number of collections based around one remixer, and you’re starting with Shep Pettibone. How did you get involved?

Arthur Baker: Well, Wayne [Dickson], who works with Demon Music, is an old friend of mine. And actually, probably around 10 years ago, I mentioned this type of project to Sony. I was like, “You know, there’s all these great remixes who haven’t got the credits that they deserve”. Like John Luongo, Bruce Ford, Shep; all the people that we’re talking about doing now. And the record labels had no interest in 12-inch remixes. I would go to Sony and I say, “Here’s five records I did that you guys now have through RCA, BMG, whatever. And they couldn’t even find them on their system. It was things like a remix of Daryl Hall‘s ‘Dreamtime’, and a Cyndi Lauper one, so there were literally mixes by major artists, and they couldn’t even find the fucking things on their system! And then Wayne did a compilation with John Luongo, a couple years back, which I love. John is sort of a mentor of mine – we were both from Boston, so you know, he was sort of the first guy out of Boston to really make it. And then Wayne called me up and said, “I’m planning on doing a project. And we’re gonna do Shep first, you want to get involved?” And I said, “Sure”. Because obviously, I’ll know all the other remixes. So it’s sort of a cool thing to do, to curate and bring attention to people. Some people who haven’t got the attention, obviously, Shep got a lot, but then he dropped off the face of the earth.

Well, that’s the thing, because there’s there’s plenty of remix compilations around but you rarely ones where it focuses on one remixer. And normally, that’s because it’s such a challenge to licence all the stuff from all over the place.

Well, that was that was definitely my idea 10 years ago to do compilation based upon the remixer. Being a remixer to myself, and I thought it would be really good to do that.

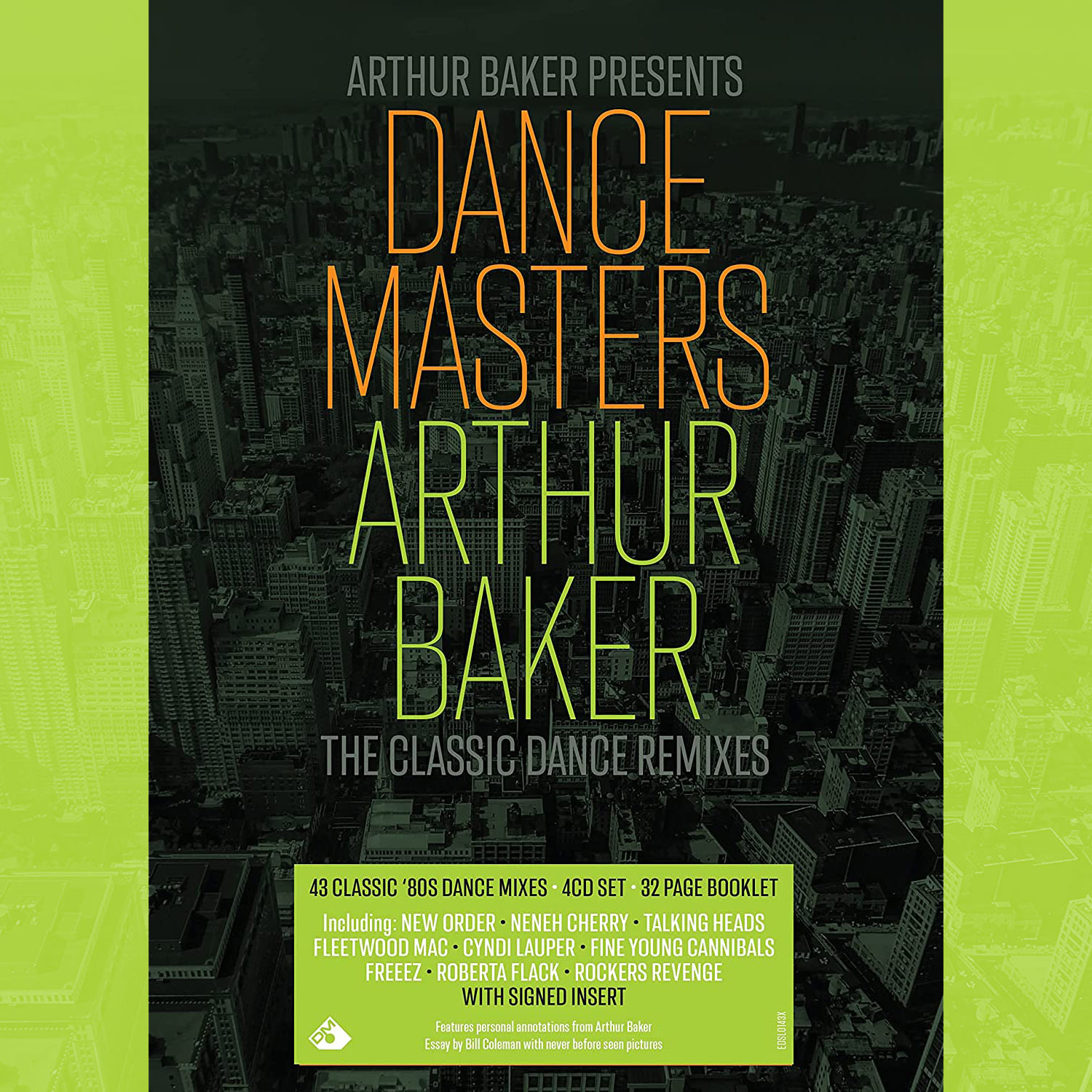

Is there is going to be one with all your remixes as well?

Yeah, there will be. I think probably number three.

So with this Shep Pettibone collection, did Wayne do the nuts and bolts in terms of putting it together? Were you involved in terms of creative input and picking tracks?

Oh, yeah, I did. I did. But I I’d have to be honest that on this one Wayne did a lot of work. But I mean, a lot of the remixes for the project, were actually mixed in my studio, that’s the other thing. Especially the earlier ones like 1983, ’84, ’85. A lot of the real poppy ones – I’d hear those over and over while Shep was working on them.

So what studio would that have been?

It was Shakedown Sound, my my studio in Manhattan. And Shep worked there for like a three-year period. He did all his records there. So I was actually there while a lot of those mixes were being done.

The 1980s was this golden age for the remix, wasn’t it? And New York was the epicentre for DJs, with all the clubs.

Oh yeah.

You guys were kind of like pioneers in a way…you, Shep, Jellybean and the like.

There was a generation before us. We were sort of second generation because in the 70s, they were they were remixers like Jim Burgess and Luongo. They were DJs who were actually doing disco mixes in the 70s. And I’d say Francois [Kervorkian], he started in the 70s. I mean, my first record 78/79, so I guess I did too, but what made the ’80s different was that technology became different. So you could easily do remixes and change things with drum machines, whereas earlier, no one would do overdubs on remixes. I would say John Luongo was one of the first – if not the first – because he put percussion on. He’d worked with this guy, Jimmy Maelen and he put whistles, percussion, not not much keyboards, but he would add percussion, you know. And then a lot of the other guys started doing that. That’s sort of a turning point, I think.

But you guys took the remix out of the disco genre and took it into mainstream pop/rock.

Oh, yeah, it did change. In the mid-70s everything became disco. So they would do disco mixes. Some of them were amazing and some of them were crap. But towards the end of that Luongo did the percussion, and then when we started, it was just it was a continuation of what he had started. Because literally, when I went in, I always wanted to add stuff to it. Other Guys, didn’t. You know, other guys would just work with what they had. Shep started adding things.

How would you get commissioned to do a remix in the first place?

They come to you. The record label. It wasn’t the artist. It could be anyone from a marketing person to like, a dance A&R guy. There were many different ways it went. For instance I’ll get specific because it’s, it’s an interesting story. I got a call from Michael Ostin, who was the head of A&R VP at Warners, asking me to come in – he had a track for me to play. And while I was going in, there was a guy there who was the head of dance promotion. This was ’86. And I went in, I heard the record. It was ‘Big Love’ by Fleetwood Mac. And Michael Ostin said “Do you think you could do anything with it?”, and I said, “Yeah, yeah, I think I can make it a number one dance record”. I heard it right away. I walk out and the head of dance promotion is there. He says “Oh, what did Michael want to talk to you about?” and I said, “He wants me to remix Fleetwood Mac’s ‘Big Love'”. He was like, “That’s not a dance record”. I said, “Well, I’m going to make it one”, and it did become number one. But that was a situation where the A&R guy [Michael Ostin] had seen me on TV in London, after I’d done the Living in a Box remix, he saw me talking about how I had made it into a hit and he said, “When I heard that, I really thought you could do that with ‘Big Love'” and it and it worked out.

So it would be things it would be like that, or your manager would get a call from the label. “Can you do this?”. They’d send you a cassette, you’d listen to it. And you’d either take it or not. I passed on a few biggies, I’d have to say…

Care to name any names?

Okay, I passed on Tears for Fears and ‘Shout’. Because it was a really downtempo and back then, with the technology, you really couldn’t speed things up in a usable way. But Steve Thompson and Michael Barbiero did a great job on it. So that’s one that’s probably the main one that that got away. But then, you know with [Cyndi Lauper’s’] ‘Girls Just Want to Have Fun’ Jellybean did the first mix and they didn’t use it and then I mixed it and they used it.

Did the labels know what they wanted, when they asked you to remix a track?

No, they didn’t really know what they wanted. Well, some did, if the A&R guy was a DJ, or an ex-DJ, some of them were more tuned in and they were more specific. But then others were all just, you know, “make it danceable” or they’d ask you to “do what you did on that other record, for my record”.

Because I imagined the goals might be things like, “we want it to be played on the radio” or similar.

No, it wasn’t even about the radio back then, it was about “we want Bruce Springsteen to get club play”. Or maybe get played on WBLS, more of an urban radio station. So they’d want like rock to go urban; urban to go, you know, indie [laughs]

I think that would be something many people in the UK don’t necessarily realise and that’s how American radio is very segmented.

Yeah, totally different. The UK, back when I was having all my hits, back in the ’80s, it had a national radio station. You know, America never had one. I mean, the closest that came to having a national radio station was when MTV was really big. Because that was a national radio station. That’s why it was such an interesting thing. Because it took the place of a BBC Radio 1, you know, it was it was more that everyone would watch this one station, whereas in England, everyone would listen. Then they’d all watch Top of the Pops, which I always thought was super interesting, because you have the your grandmother, young kids… everyone’s watching Top of the Pops. So it was so powerful, and, you know, really cool. It was great.

So okay, you take on a remix job. What would you normally deliver, as a matter, of course? Was it like three or four versions – a dub mix, a 12-inch mix, etc.?

That came a bit later. The more people did those, the more they expected them. But the label would want a really safe version and then you’d want one where you could do more. So going back to Living in a Box, the mix I did that I first turned in, it was it was not experimental exactly, but it was just like, the kind of mix that I would like to do. I dropped the drums out at one point and just had the bass line, and I’ll never forget because Peter Edge – who’s now Pete Edge and is now a huge person in the industry years later [currently CEO of RCA Records] – he was like, “Oh, you got to take that out. Because if you don’t have the kick [drum] in, people won’t be able to keep dancing”. So I had to take that out, but I put it in on the dub. So the dub has all the big drops and stuff. Now obviously, all that shit’s in every fucking pop record, they take out the drums…

Tell me about the logistics, because you were mentioning technology had improved and you had drum machines, but I imagine it was all still analogue multitrack tapes, back in 83/84?

Yeah, but we were getting drum machines and syncing up with SMPTE [timecode generating system] you were able to sync up a drum machine basically, and you could make a click track. So that all happened in 82/83. But I would say most of Shep’s mixes on this project were after that.

But what I’m getting at is that they would have to duplicate the multi-track tape and then physically send it to you.

Oh yeah, they give you a copy of the multi-track, so you could erase whatever you wanted. Or you could make another copy, which is what we used to call ‘slave’ copies, which isn’t a very PC now, but you’d have a clone. But then, I’d say 1987/88/89, around then, that is when people started throwing the song out and you know, just sampling the vocal and doing that. Most of the mixes Shep did, he kept the full song.

I much prefer the classic treatment where you maintain the structure of the song

Yep. You know, I do too because you keep the song and it’s about the song. But, you know, there’s obviously was a place for both of them. But the people who are better at the other ones couldn’t really do the ‘song’ ones. But then again, Todd Terry did some great ones using the song as well, like [Everything But The Girl‘s] ‘Missing’, so he did quite a few that were great in both ways.

Were the record companies getting permission from the artist? You mentioned Fleetwood Mac. I wonder if they would have been on board with having their songs remixed?

Lindsey Buckingham wasn’t on board. What happened was, with ‘Big Love’. I actually met him. You don’t really usually meet the artist, with remixing, it’s not common at all. But I was in LA, I had to go pick up a copy of the tape at his studio, which was in his house. So I went and he played it for me, and it was great. You know, it was really cool; he’s a great guy. And as I took it away, I said, “Do you have any suggestions? Anything you want me to do?” and he said, “No, just do your thing”.

So when I went in [to listen to the multi-track], and there was a great Stevie Nicks vocal on there that wasn’t really used on the original. But it was on the tape, so I think it ought to use it. And then I did take his bass off and put like a house bass line on. I assume he wasn’t happy with this bass going missing and he wasn’t happy with his ex-girlfriend getting the lead with him. When I finished it, the record label loved it, but said “You know, we got to send it to the group”. And Lindsay didn’t really want her vocal on it, you know, it’s supposed to be his lead. So I ended up doing like, again, a dub with her vocal – he didn’t care about that. And, you know, the new bass line sort of made the mix, with the piano. ‘Big Love’ was probably the first house remix of a rock record. I can probably say that 100 percent, because house had just started with 1986/87.

They were obviously quite happy with those now, because they included all those remixes on the Tango in the Night reissue box set.

Yeah, yeah, they did. And I was happy with those remixes. And ‘Family Man’ – both of them.

So Arthur, tell me, how long would these remixes take you to do?

It really depends. Some would be really quick and you’d just do it. But what happened was, the more drugs you did, the longer they would take! So if you had no drugs, you wanted to get out of there quick. If you had a lot of drugs, you’d stay there for days. If I’m being honest, it would be like a party in the studio. Once we started getting bigger budgets and more time, and because I own my own studio, I could keep the mix up for a day or two.

The more drugs you did, the longer the remixes would take

Arthur Baker

Same with Shep, I’d let him keep the mix up. So we’d be in there. He’d been doing his mix, I’d come in, we’d hang out in the studio, and then he’d lose the plot a bit and I’d say “You can leave it up and come in and finish it in the morning. But I had the luxury of having my own studio, you know, so it was it was definitely a different time. Like on The Rolling Stones remix of ‘Too Much Blood’ [from 1983’s Undercover] that I did. I probably have 20 reels of parts. I still have all the tapes of that.

In the beginning, you’d edit as you would go, because you had limited studio time. So you’d actually do a version, your 12-inch mix would be edited, you do the edits there. And then you take a couple of reels of passes and then mess around with that for the dub. And and then once it became computerised, you’d put the main pass in the computer, and then you could take a pass, spit it out and have one with a higher vocal, lower vocal, background, you know, you could do all your passes, which you would you have the engineer do, you wouldn’t have to do that once you put it all in. So it was changing with the technology, actually.

I always think of you, you know, on your own, running around like a wizard in a studio. But was that the reality? Did you have a team of people helping you?

I always had an engineer, and an assistant to make tea, or do the drug runs, or whatever [laughs]. But we always had that. And, you know, usually I’d have like one musician, who’d come and do overdubs. I mean, that’s a like the standard team, of remixing. And then later on, I had the editors to edit. But the whole thing with the editor, it was more about not wanting to sit through all the passes that I had done [laughs]. So I’d let the Rascals, The Latin Rascals, do it. Or Junior Vasquez, who was my editor for a while. Or Victor Simonelli… any of those guys. I’d say, my early remixes where we did the edits, right while we were doing it, were some of the better ones because I didn’t I didn’t throw control away to people cutting tape, you know? I would like really do it in the studio and just get it done.

How did the budgets work for these things? Were the labels throwing bucket loads of cash at you? Because they had to pay you to do the remix, but, presumably, they also had to cover the studio time?

Yeah… I mean, when I owned my own studio, I was laughing because, you know, they’d give me an ‘all in’ budget and I’d keep 95 percent, or 90 percent of it, you know? Probably the biggest budget I got was I think Paul McCartney [Baker remixed ‘No More Lonely Nights’], where I got 25 grand or something, The Stones was probably 25 grand. And while the engineer made decent money, it wasn’t anywhere near that money. And you’d pay a keyboard player $400 or something. So I probably made like, 22 grand, you know, because it was my studio. When Shep did his remixes in my studio, he had to pay three grand a day for studio time and all that.

I’m glad you mentioned Paul McCartney, because I’m a big McCartney fan. And of course, you did the ‘No More Lonely Nights’ remix

[Laughs] Yeah, I won’t say it’s one of my better works, you know.

Well, can you can you shed a little light on the process around that specific example?

Well, it was more like, you know, he offered a lot of money, and I love the Beatles. And I got that song. And I had to deal with the song. And it wasn’t like I could sample one line of the song and do a house beat. I had to sort of keep it somehow in that vein. I’m sure it will be on ‘my’ Dance Masters box set. There’s some remixes you do strictly for the money, if it’s a lot of money. I mean, in the beginning, I did none of those. I just did things I really loved that I could do something with. And then at some point you do a few that you do more for the money rather than it being about what you think you could do with it. But I always thought I could do something with a with a song. I thought I could do something with anything. If it was a song I couldn’t stand to hear, then I wouldn’t do it. Because there’s nothing worse than listening to a song over and over that just does your head in.

I always thought I could do something with a with a song. I thought I could do something with anything

Arthur Baker

The Springsteen remixes I did I’m really proud of because they were all three really different types of mixes and songs [Arthur Baker did multiple mixes of ‘Born in the USA’, ‘Cover Me’ and ‘Dancing in the Dark’). And I think they all did what they were meant to do. He was happy with them. And and and they still sound good. I got death threats for ‘Dancing in the Dark’ on the radio, someone was like, “Someone should kill that guy!” on the radio on one of the rock stations like K-Rock or something. The guy said “Bruce can’t possibly know that this is happening”. But actually, Bruce was in the studio with me, he actually came to the session Bruce. We were in the Power Station [studio] and the lost power and the AC went off so Bruce just went out and bought the beer!

And would you get paid more money for doing these bigger names like Springsteen and McCartney?

Yeah, for sure. Of course. Because I would also do remixes for newer groups and artists. I was doing a lot of UK groups when I first made it over there, I got bombarded. I came over in 87 and I had never been over. And then literally the first one I did was Neneh Cherry, which did really well and then Living in a Box did well and then living in a box. So after that I got tons of work and I was remixing everyone for a time.

Why would people come to Arthur Baker instead of Shep Pettibone or Jellybean. What were they after? What were they looking for?

I think in England, they came to me at that point, because I’d been really successful as a producer. I’d had all those records out like New Order, Freez, Rocker’s Revenge. They all came out in a short period of time and I’d never shown up in the UK, so it may have been that, but in other cases I don’t know. I would hire Shep before me! [laughs].

Shep Pettibone had great ears and was much more meticulous than I was.

Arthur Baker

As as I say somewhere in this box, that his ears were like radio ears. He had great ears and he was much more meticulous I was more of a punk remixer… I wasn’t that guy. I would have liked to have been that guy. But that was just wasn’t me. I did a lot of those early rock ones, but then you know, Shep was doing Depeche Mode, but a lot of the things he did, he did after me. So I did New Order then he did New Order. I did the Pet Shop Boys, then he did the Pet Shop Boys. So people who were into me, like the Pet Shop Boys would also have been into Shep, and the same with New Order.

The Pet Shop Boys is an interesting one, because you did ‘In The Night’, which is a great remix, and you also remixed ‘Suburbia’, but those never really came out in the UK. How much did you keep tabs on your remixes after the event? So for example did you get pissed off when it it only went to promo stage and not full commercial release?

I may not have known about it in that case, but you want your mixes to do well, obviously. When ‘Living in a Box’ became a big pop hit, I think my remix had a lot to do with that. And that was great. And it got me the Fleetwood Mac gig, you know, so it’s sort of it’s more like promotion. They promote your work. And then obviously the one that we probably won’t talk about, because it was years later, was my remix of ‘Spaceman’ by Babylon Zoo. I mean, that was the biggest selling remix of all time; still is, I think. So you know, you’d like them to do well. I mean, you don’t want it to not come out. I did a John Cougar Mellencamp remix that never came out. I don’t even have a copy of it. It was it was pretty good. But he was sensitive about what, for whatever reason.

One of the things, like with the Pet Shop Boys, I’ve noticed is that bands like to move with the times, don’t they? So they won’t stay with one remixer?

Oh, yeah, for sure. They will. Yeah, they’re very trendy. They worked with Danny Tenaglia. They were they were like Madonna. Madonna is the same way. She would find the hot person and work with them. And she she did that for many years.

Do you miss the miss the 1980s? Do you miss that golden era where you were running around like a maniac just having fun?

Well, I’ve been living in that time, for the last two years making this movie [Arthur is helping to make a documentary] so literally, my life is sort of immersed with Rocker’s Revenge and talking about the Eighties [laughs] Yeah, I miss it. If you could go back in time for a week and do all the things we did back then, it would be great. It was a great time, and the music was great. And the clubs were amazing. I mean, you can’t even compare clubs, then-to-now. There were like 20 clubs in New York that were multi-thousand [occupancy] and rocking clubs. I mean, now there’s none.

Did you ever test drive any of your remixes by nipping down to the local club and getting them to play it?

Oh, every single one! It’s funny, because as I said, I’m making this movie and and I used to bring them to the Fun House famously, as you see in the New Order video [for Confusion], that’s me, taking the reel-to-reel to Jellybean to play it, and that’s what I would do. I’d go to the Fun House, go to Danceteria even before it was done. I’d bring a tape or a cassette and have Freddie Bastone or Jellybean play it. I’d come in with something, they’d like to listen to it for a second and they play it right away for me! You don’t have that now. No one does that anymore.

That’s amazing. So even before you’ve given it back to the label, you’re checking out the reaction…

The label wouldn’t even heard it. This is when I’m still working on it. This is a work in progress. Testing the sound and testing reaction of the crowd.

So you might make changes based on how it goes down?

No, you would make changes. The thing is now, a lot of DJs are such idiots, they’re like afraid to test their tracks. You know, you ask “are you playing that out yet?” and they’ll say “Oh, no, it isn’t ready”. I’m thinking well, maybe you’ll find out that it is ready. If you play it in a crowd. You know, they’re all really afraid, which Jellybean wasn’t. He knew what I was going to give him was going to be right for him. He’d listen to a bit of it, not even all the way through. And then, you know, then he did a lot of mixes with me, so it was it was good.

Would the with the labels ever reject anything and say “this isn’t what we wanted?”

I went for many years without having a rejection, I have to say. It was like a couple of years. I think the first one that got rejected was the John Cougar Mellencamp.

But you would still get paid for that? I mean, you hadn’t done anything wrong, as such.

Yeah, yeah. I mean, the record label might go, “Oh, can you change this and that”, and I would do it. You know, it wasn’t like I wasn’t being precious about it in that way. Working with someone like [Arista President] Clive Davis, you know, he would really put you through the wringer. I did a few remixes for him and a few productions, and he was really hands on. He would get really super-specific.

I’m guessing you wouldn’t really like people coming down and looking over your shoulder. That would be like, “go away, leave me alone”.

Well, when Diana Ross came in and we were mixing [her 1984 album] Swept Away, that was fun. It depends on the artist. If it was going to be someone really critical… I mean, Springsteen was great. He was just saying, “Oh, so what are you doing there?” And he was really interested. He had never given anyone a multitrack of his shit to go work on without him being there, you know, so that was sort of fun for him. I mean, not many artists would come to the studio – Cyndi Lauper did for for ‘She Bop’ [Baker created the 6.16 Special Dance Mix’] . I mean, I wanted to meet the artists in a way. I wanted to get to know them and maybe work with them and on other things.

Have you got like a massive archive of old tapes that no one ever asked you to return?

Yep! [laughs]. At the beginning of this film I’m making is me and my storage room with all these big tapes and everywhere. That’s how the film starts.

You’ve had a very long working and personal relationship with New Order. You must be proud of that?

Well, we are good friends. You know, me and Barney and me and Hooky are really close friends. They are two. of my best friends. Unfortunately, they don’t talk to one another, so it makes it difficult. I invited both of them to my wedding, about 11 years ago. And Hooky answered first and so Barney didn’t come. But I’ve done tracks with Hooky, I do remixes for New Order and I DJ for both of them, so it’s fine. Of course when I’m with one of them, they do ask what’s going on with the other, but I’m pretty diplomatic.

What do you think technology has done to the, to the art form, if you want to call it that? Because the problem is, it’s so easy to do things. There’s so many options. Has that taken away a lot of the creativity do you think? Or has it made it more creative?

Well, I think it depends on who you’re talking to. Some people, it’s made more creative, who would never have done anything without the technology, and they can use the technology way better than I could. The thing is, I don’t try to stay with the times. I try to do my own thing. I’m making records now the way I have since the day I got my computer when things changed so that I could make records on my own. I haven’t gotten any new technology, literally in 15 years, probably. I’m just using logic, and I just make my own music in it. I may have a percussionist play on top and keyboard player, or whatever, but I’m not I’m not trying to get the hottest new plug-ins.

When I did those remixes, I tried to make the original better and add things that I heard in my head that would make it a better record

Arthur Baker

And when I do a remix, like I just remixed New Order’s Be A Rebel, that’s like a classic remix I would have done in the 80s and a lot of people have said, “Wow, that’s really good. It’s the best one of the 30 remixes, they had done just because you made their original track better”. When I did those remixes, I tried to make the original better, you know, add things that I heard in my head that would make it a better record.

Arthur Baker was talking to Paul Sinclair for SDE.

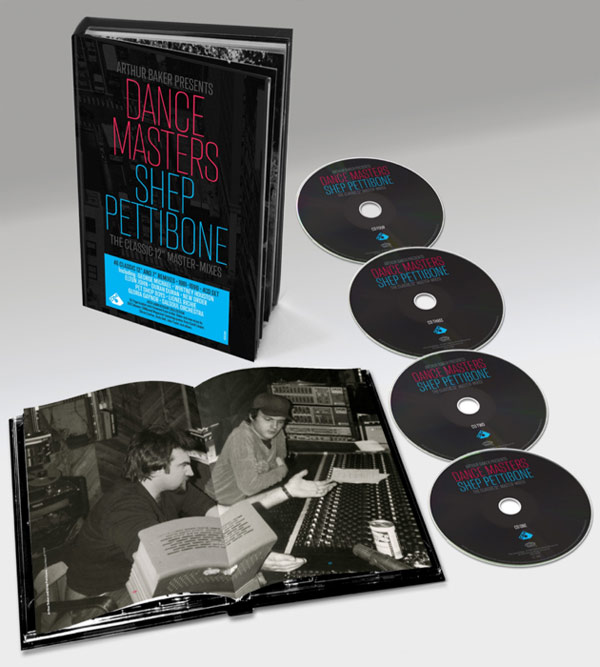

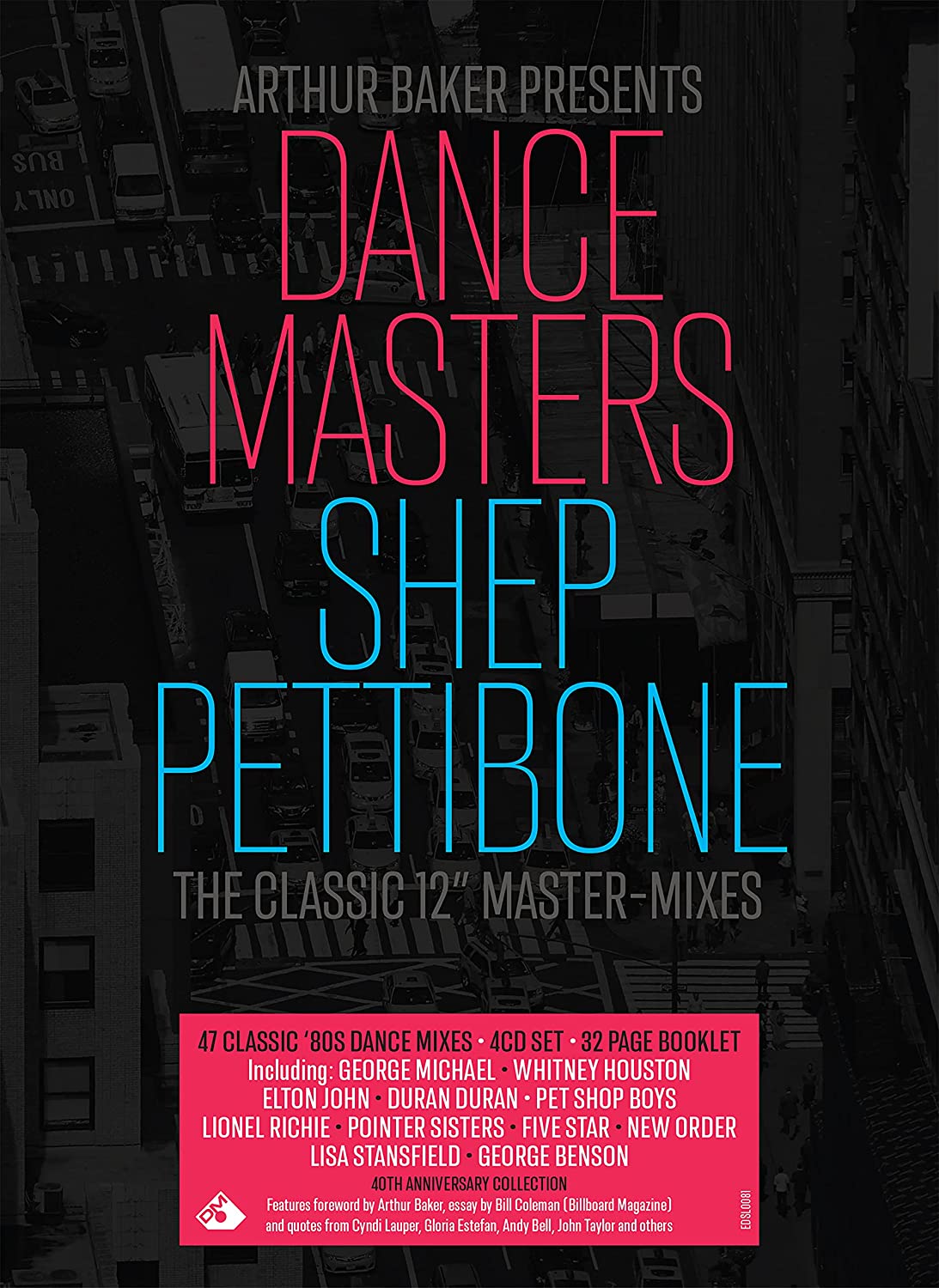

Arthur Baker presents Dance Masters: Shep Pettibone is released on Friday, 1 October 2021. It’s available as a four-CD set or on two 2LP vinyl sets.

Compare prices and pre-order

Various Artists

Dance Masters Shep Pettibone - 4CD set

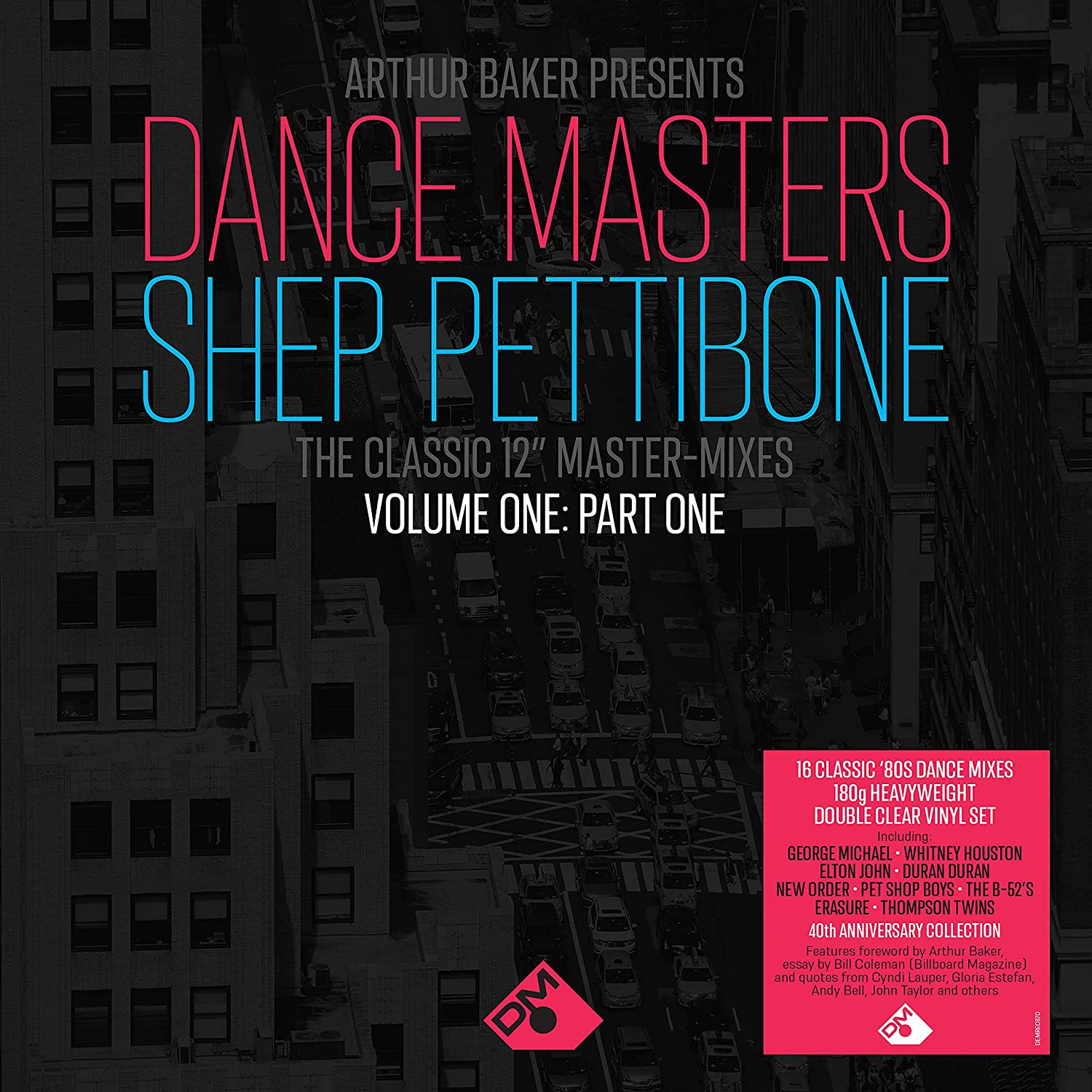

Compare prices and pre-order

Various Artists

Dance Masters Shep Pettibone Vol one part 1 - 2LP clear vinyl

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Compare prices and pre-order

Various Artists

Dance Masters Shep Pettibone Vol one part 2 - 2LP clear vinyl

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Interview

Interview

By Paul Sinclair

37