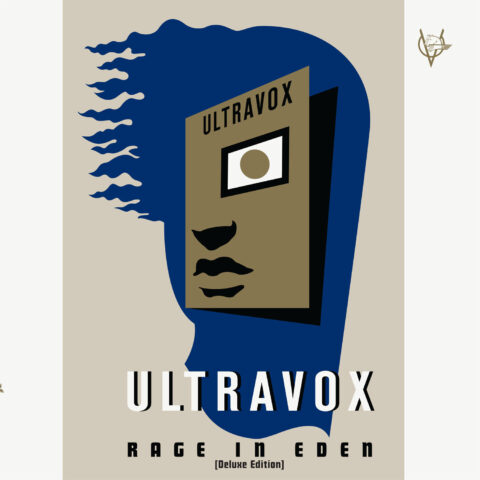

Midge Ure on Ultravox’s Rage in Eden

“I’d forgotten how good Ultravox were”

Midge Ure discusses the Ultravox Rage In Eden reissue, his initially conflicted thoughts on Steven Wilson’s new mix, the joys of hearing long-forgotten demos, his two new solo albums and the possibility of another Ultravox reunion. John Earls asks the questions for SDE…

Hi, Midge. How does it feel to have Rage In Eden coming back out into the world?

Midge Ure: It’s great. It was a brave record to do and, along with Brilliant, it’s probably my favourite Ultravox album. With Vienna, we’d toured most of its songs before going into the studio, so it was incredibly quick to record. That was only three weeks. Rage In Eden was three months.

Of course, for most of the band, Rage In Eden was their fifth album, but it was only my second in Ultravox, so it could have easily been my difficult second album. Most people expected Vienna part two, but we didn’t want that.

We went off to Conny Plank’s studio in the middle of nowhere outside Cologne with no ideas. We might have had a riff or a chord change, but we had zero songs and we created the entire album in the studio. Conny’s studio and his creativity became an instrument. We were either incredibly brave or incredibly naïve and stupid, but it turned out very well. We made an album we couldn’t have made under any other circumstances, I think.

Did all four of you think it was a good idea to have nothing prepared?

We were all up for the experience and the experiment. Once you get commercial success, you get an invisible power. We had a cockiness and bravado, plus Vienna wasn’t an obvious hit record. It had bounced around the world, which gives you a spark and arrogance you hadn’t had before.

Making it that way was youth too: we were all quite young, as well as having self-belief. You don’t doubt you’ll come up with something interesting in the studio. Whether that would mean hit records, who knows? Nobody knows what will be a hit song. All you can judge is whether it’s an interesting piece of music or not. It’s someone else’s job to then get it played on the radio.

It was a combination of naivety and cockiness to think it was perfectly acceptable to go into the studio with nothing

Midge Ure

So, it was a combination of naivety and cockiness to think it was perfectly acceptable to go into the studio with nothing. We knew we had three months to make it, though if we’d known what that would cost we might have tried to do it in one month. But it was a great way to do it. I’ve never spent that amount of time on one project before or since, and it was great to do.

Did the fact Vienna was such an unusual album to be a success feed into that confidence?

Oh, absolutely. It gave us an extra spark, because something that wasn’t obvious had become so hugely commercially successful.

Also, we were incredibly lucky that we were with a label who left us to our own devices. Chrysalis never interfered. They never suggested: “Where’s the single?” or “Here’s your artwork, and here’s your latest video that we just need to stick you in somewhere.” All of that was left to us, so we worked with Peter Saville on the artwork and we delivered the videos. That was a very unusual scenario.

We were in a very lucky and privileged position, being allowed to dabble away and not show Chrysalis anything before the final album. Their input was us saying: “Choose what you think the single might be.”

After making Vienna with him, was Conny Plank always going to produce Rage In Eden?

He was always the only one on the horizon, certainly for me. If you wanted to experiment with recording techniques, Conny was your man. He was very much an engineer, but he also wanted to experiment as much as anyone else.

Conny was a huge fan of Lee “Scratch” Perry, of throwing the faders up and having fun, which wasn’t what you’d expect from a German producer. It was imperative we had someone like that, rather than someone going: “Oh no, that dial has gone into the red. We’re going to have to do that again.” Conny’s attitude was much more: “Let’s take the orchestra and put it in a distortion box.” He was very much a fifth member of the band, as George Martin had been for The Beatles.

Just how remote was Conny’s studio in the village of Wolperath?

It was in a barn that was very Germanic, bordering on hippy-ish. Conny had developed that studio, and he was the only one who could work it, especially once he’d changed the mixing desk. He’d built a new mixing desk to a spec that only he could understand. It was his baby.

The studio was so remote that there were no distractions. There were no video games, no satellite TV. It was a big day if we received a parcel from the UK containing Fawlty Towers cassettes. It meant there was nothing whatsoever to do except work on the record, and that was no bad thing. You’d see Warren writing lyrics on a typewriter, Chris playing bass in the sunshine; there was always something going on.

It was a bit like that on Brilliant too, when everyone came to my house in Canada. We all lived there making that album, where there was a mini studio for everyone to work together or individually. It’s a modern way to do it, but we were doing it in a farmyard in 1981.

How soon was it before the album took shape?

It’s difficult to say. The other guys might have better recollections, but I remember the whole record being a malleable, ever-growing thing. We didn’t make it one song at a time and onto the next one. We’d have songs in various degrees of development, going back in to say: “Let’s do this lyrical angle” or “Why not try recording that backwards?”

It wasn’t writing a bunch of songs around the piano and recording them in a linear fashion, it was jigsaw pieces, done piecemeal. We pulled and pushed the ideas, knowing instinctively when to stop.

Is that experimentation why the last three songs merge together – that it felt natural, rather than the band making a big statement with a song trilogy?

Yeah, it just all flowed. We wanted everything to connect together, which meant sonic skills only Conny could achieve. We’d spend hours mixing a track, putting them through weird and wonderful concoctions. Conny was great at it, as he had been on Vienna too.

Conny would describe songs so vividly. On Vienna, he’d said: “I see an old man playing piano in an empty ballroom. He’s playing the same tune he’s played for 40 years and he’s very tired.” And that’s the piano sound on that song. On this album, it was: “Wouldn’t it be great if the song is disappearing through space, with radio waves crumbling and breaking up, before at the very last second you hear someone turning it off?” He did just that. We’d listen to the results, going: “Wow, that’s great!” That side of the sound was more of a language than speaking English to Conny.

Speaking of language, on Rage In Eden your vocals and lyrics seem more of an instrument rather than telling a straight narrative story in the songs.

We always said my voice was another instrument in the band. We used to get lambasted for my voice being too quiet, but I didn’t want the vocals to crowd the rest of what was going on, because it’s part of the music. Yes, that is especially the case on Rage In Eden.

There was a lot of cut-and-paste Bowie-esque lyrics, so that each line was like soundbite from a movie or a book

Midge Ure

There was a lot of cut-and-paste Bowie-esque lyrics, so that each line was like a soundbite from a movie or a book. The songs didn’t necessarily have to tell a story, it was about a song giving you an overall image, a picture of what it was about. Its story was created from those images.

This was at a time when music was allowed to be experimental, where you could play around and still have a chance of getting on the radio. Very soon after, it had to be three-minute pop songs but, at that moment, there was space to experiment. If it was a good enough tune with a catchy hookline, you could be in.

Did three months feel like the natural cut-off point for finishing the album?

It was all our sanity would allow. Warren crashed the studio car and broke his arm, which was an indicator of boredom kicking in, of a desire to get back out and about. Luckily, he’d managed to have all his drums done by that point.

We didn’t do anything else while making the record, and the only people we saw were musicians visiting Conny’s studio. Holgar Czukay would come to edit his mad albums when we were done for the day, and Hans Lampe from La Dusseldorf would hang out. But they were the only other people, and three months of that is pretty intense. It started to feel like a penance. The second half of a double album for another three months? No, thank you.

Did Rage In Eden feel like it was a special album while you were making it?

I didn’t know if it was special, or if it’s special now. It’s special to me, but I don’t know if it is to anyone else.

It’s got a reputation as a real fans’ favourite.

Does it? That’s interesting, and I’d like to think that’s the case. Very soon after Rage In Eden, although we didn’t intend it, we started slipping down a slightly poppier slide. Working with George Martin on Quartet, things got a bit more polished. The rough edges were no longer there, whereas Rage In Eden is full of rough edges.

That album has an edge, an ambience, a darkness that you can’t contrive. It was a reflection of where we were and who we were at that moment. If you spend three months in the German countryside, you’ll have your highs and lows. That’s reflected in the music on that album. But you can’t see that while you’re actually doing it. It’s only later when you play it as an album and when you see people’s reactions that you think: “Hold on, that’s quite dark and intense.”

There were certain songs we couldn’t have written if we hadn’t made them in that way. You couldn’t sit at the piano and write Your Name (Has Slipped My Mind Again). We couldn’t see the final picture while we were making it, but we could see that an interesting picture was coming together. When it was finished, we were all happy with it. It’s a great example of a band working well together.

How did Chrysalis react when you presented the album to them?

I can’t remember. They didn’t demand any changes. They realised they’d have a very good chance of commercial success irrespective of whether they were the most commercial songs or not, because it was coming off the back of Vienna. I don’t recall any major upheaval, it was just us going “There you go” and, once the artwork was done, going straight into tour rehearsals. By the time we gave Chrysalis the album, we were already thinking about the tour.

How did Peter Saville come to design the artwork?

Chris Allen (Christopher Cross’ real name) had seen some of Peter’s artwork for Factory. Vienna had similar artwork to Joy Division’s Closer: both black-and-white, both landscape photographs. That was interesting, so we approached Peter and it was a marriage made in heaven. We were slow making the record, and Peter was even slower making the artwork.

Peter got the feel of it all and I couldn’t imagine anyone else doing it. With this reissue, we want to hold Peter’s artwork up to the light, to say that he created it all. We’ve a huge love and respect for Peter.

Did Peter’s artwork look perfect straight away?

He had to explain the logic to us a couple of times. His artwork was always strong and entertaining, but it didn’t always connect with what we thought the album was saying. We had to tweak it to get it back on track, but the end result is fantastic.

Peter borrowed the idea from a film poster. We got slapped on the wrist for copying that, so Peter came up with an alternative that was great, with the same Dali-esque feel. There’s a lot of imagery in that sleeve, which Peter was great at.

Rage In Eden’s second single, The Voice, had the first of several Ultravox videos co-directed by you and Christopher Cross. How did that come about?

We’d instigated the style of Ultravox’s videos since Passing Strangers: the parameters of shooting in 16mm film, cropping the screen to give it a film noir, grainy high-contrast look. By the time of The Voice, we thought we knew enough to jump in and do our thing.

When I look back now, our videos are a bit literal. We were too contrived, and we could have made those videos more haunting. But it was a bit of fun and, at the time, they were fine. They’re not the greatest videos, but we had our moments. We were interested and we had a bash. Love’s Great Adventure is a fun video, much better than the previous ones.

What was the Rage In Eden tour like?

We felt a bit under-rehearsed, but that was always the way. Commercial success is weird, because a song that’s had an average reaction six months earlier will get a ludicrous roar from 4,000 people if it’s since been a hit. It doesn’t change what you’ve done, but people’s perceptions of what you are become completely different.

Touring a hot follow-up album is easy. Once you’ve got the nuts and bolts in place – the design, the setlist, rehearsals – and you step on stage, it’s easy. Rehearsal was the hardest part, as we never used tapes or pre-programmed anything. That was a good tour, an easy time.

What do you remember of the Hammersmith Odeon show that’s been newly added to the reissue?

We did four or five nights at Hammersmith, and you can hear from the audience’s reaction that we were shit hot. That’s funny, because for years I looked back at that time and thought it wasn’t very good. Then you hear those live recordings and think: “My God, this is powerful stuff.” How we managed to sound that good with the equipment we had, I’ll never know.

We flew by the seat of our pants and creating that atmosphere was fantastic. I can’t remember that actual Odeon concert itself, because I was on stage, in the zone and doing my thing. I was in the vortex, trying to keep the cyclone going. It’s only now that I’m outside of it that I can see what it was. The band were always good, but I’d forgotten just how good they were. Hearing those recordings reminds me of just how powerful we were.

How closely do you get involved with the reissues?

We’re all involved, and Chrysalis are fantastic in how they do our reissues. They have the rights to put it out in any old way they want, but they’re as enthused as we are in doing a quality job. They embrace the fact that we’d spend huge amounts of time and money – almost as much as making the records – in getting the artwork right.

Getting the artwork and stage sets good was so important to us. We wanted people to come away excited, to be left with indelible images of us, in the same way I had images of Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust concerts in my head without needing to see them again.

People are spending big money on something they probably already own, so it has to be an object of desire

Midge Ure on box sets

We’ve tried to get these box sets right, to make them something people respect. We take a lot of time on the packaging, so that the artwork shows a huge amount of respect to what Peter Saville created back in the day.

A boxset has to be a quality item. People are spending big money on something they probably already own, so it has to be an object of desire. It’s the equivalent of a coffee table book, something that people see and go: “Wow, look at that! That’s just perfect!” We want to look after these things, and Dermot James at Chrysalis spends a lot of time digging out our old tracks, rummaging in vaults for cassettes of rehearsals and demos. I couldn’t do that, but Dermot does it brilliantly and diligently.

What do you think of Steven Wilson’s new mix of Rage In Eden?

He’s clarified things, and he’s also found aspects like guitar and keyboard parts that we’d left out of the mix for whatever reason. That can take a couple of listens to get your head around. At first, you think: “Am I comfortable with this? There was a reason we left this out in the first place.” But, all these years later, once you listen a couple of times, you think: “Well, why did I cut it out? It sounds great!”

Steven doesn’t take any direction from us at all, because there’s no point. We love what he does, and you wouldn’t tell a brilliant rally driver how to drive, so we leave him to it. We might then say: “That piano is a bit loud there” and it’ll get tweaked, but that’s it. It’s up to Steven, and he does a brilliant job.

I’ve never actually met Steven, and I can only presume he’s a fan, because I can’t imagine someone who isn’t a fan of another artist’s work to sit there for weeks and remix it. If he’s not a fan, it must be purgatory. I love Steven’s stuff, but I haven’t heard the 5.1 mix of Rage In Eden because I’ve got nothing to play it on. Even in my studio, I don’t have a 5.1 system.

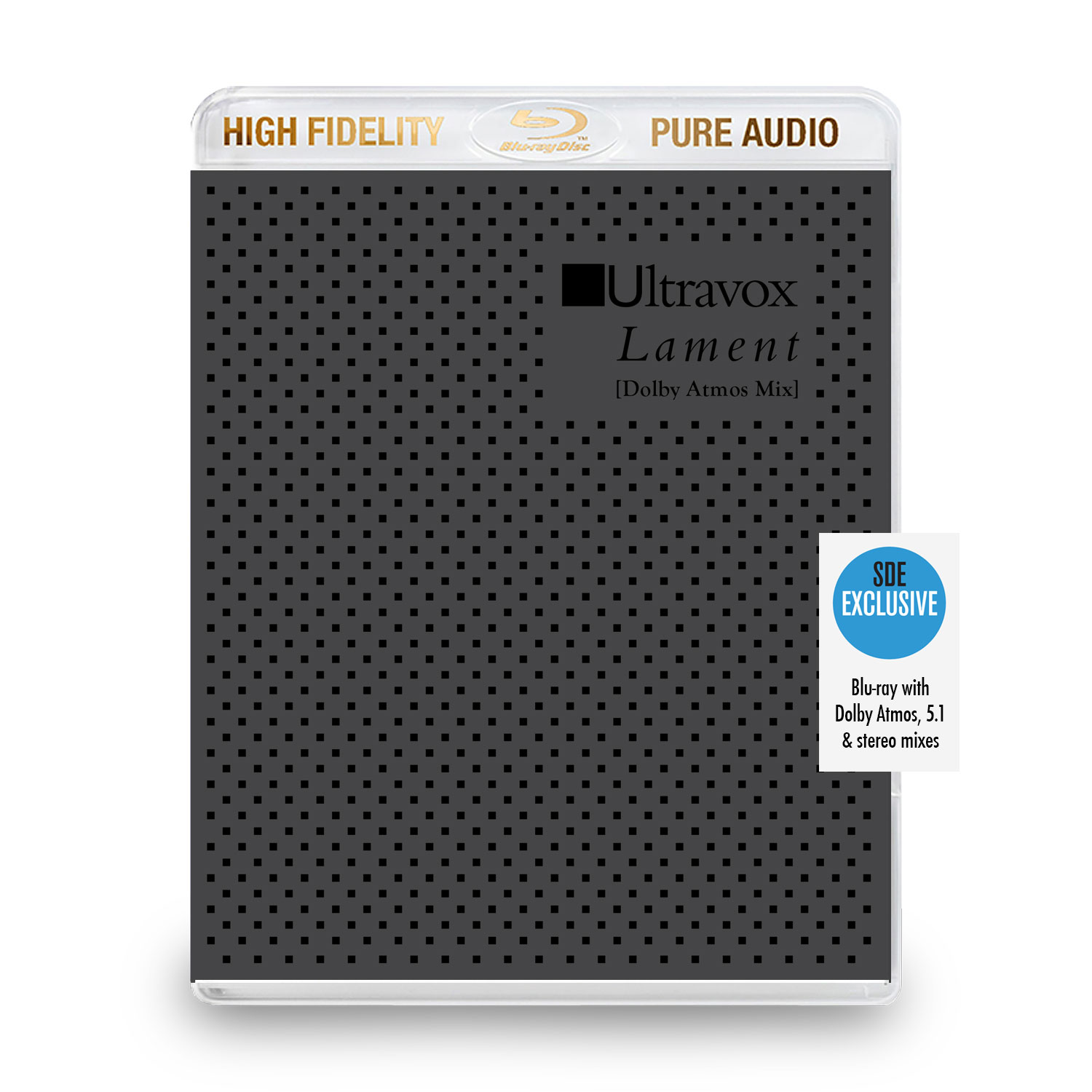

Does it follow that Quartet, Lament and U-Vox will get the same deluxe treatment?

I’d hope so. I’d love to hear a fresh mix of Quartet and I hope U-Vox finally gets a proper sleeve, though we have no-one to blame for that except ourselves.

I’d love to hear what’s in the archives myself. I’m constantly surprised by the live recordings and the half-completed tracks that never made it. We paid no attention to those demos at the time and had forgotten they existed. But when they come to light, it’s fascinating. The moment you hear it, even though you can’t remember doing it, all of a sudden it’s like a door opening in your mind. You think: “I was doing this, and then I played this.” You suddenly know where the song is going next, and the track confirms that for you. It’s strange how those memories are still accessible, given the right key.

Do any of those three albums have more potential bonus material than the others?

I think they were about the same but, again, it’s difficult to remember. Once you’ve thrown something by the wayside, you don’t go back to look at it, so I can’t exactly say what’s out there. I think what’s in the archives is a surprise to Chrysalis too. It’s great when boxsets dig up things that we and the audience didn’t know existed.

I can say that we videoed a lot of things at the time, and there’s tons of stuff that I sent to Chrysalis last year. We carried Super-8 and Super-16 cameras, and the footage needs cleaning and digitising, but hopefully something can come out of it. It’s probably a great project for an up-and-coming film editor, to go through those hundreds of tapes and make something from it: a quasi-documentary, or footage for a regular documentary that could go on top.

As you’re all involved in the reissues, how much do you talk to each other about them? You can guess what I’m going to ask: is there a chance Ultravox could do something together again?

For years, we thought we were done. Then we got back together again for two tours and an album. We’d have been stupid if we hadn’t got back together, because Brilliant wouldn’t exist, which left the band on a more satisfying note than U-Vox. All of those elements were positive.

I’ll get a business email from Billy every now and again, and there’s a friendliness there, but I haven’t spoken to him since our last show in 2013. Warren has retired and lives in Northern California. We email now and again, and have a good chat when we do. Chris lives in Bath, not too far from me, but again, we’ve all got separate lives. We’ve been individuals much, much longer than we were together in Ultravox.

Also, it’s such a male thing. I don’t know any man who’ll just pick up the phone for a chat. That’s not what guys do. Instead, we go along thinking everything is fine then, when you do finally speak, all those years just disappear.

Whether we’re fit enough to do a reunion, or whether the desire is there to do it, I don’t know. Billy has stated in the past that Ultravox is finished and he’s not doing it anymore. Whether that’s definitely the case, I don’t know. So the answer to your question is: Who knows?

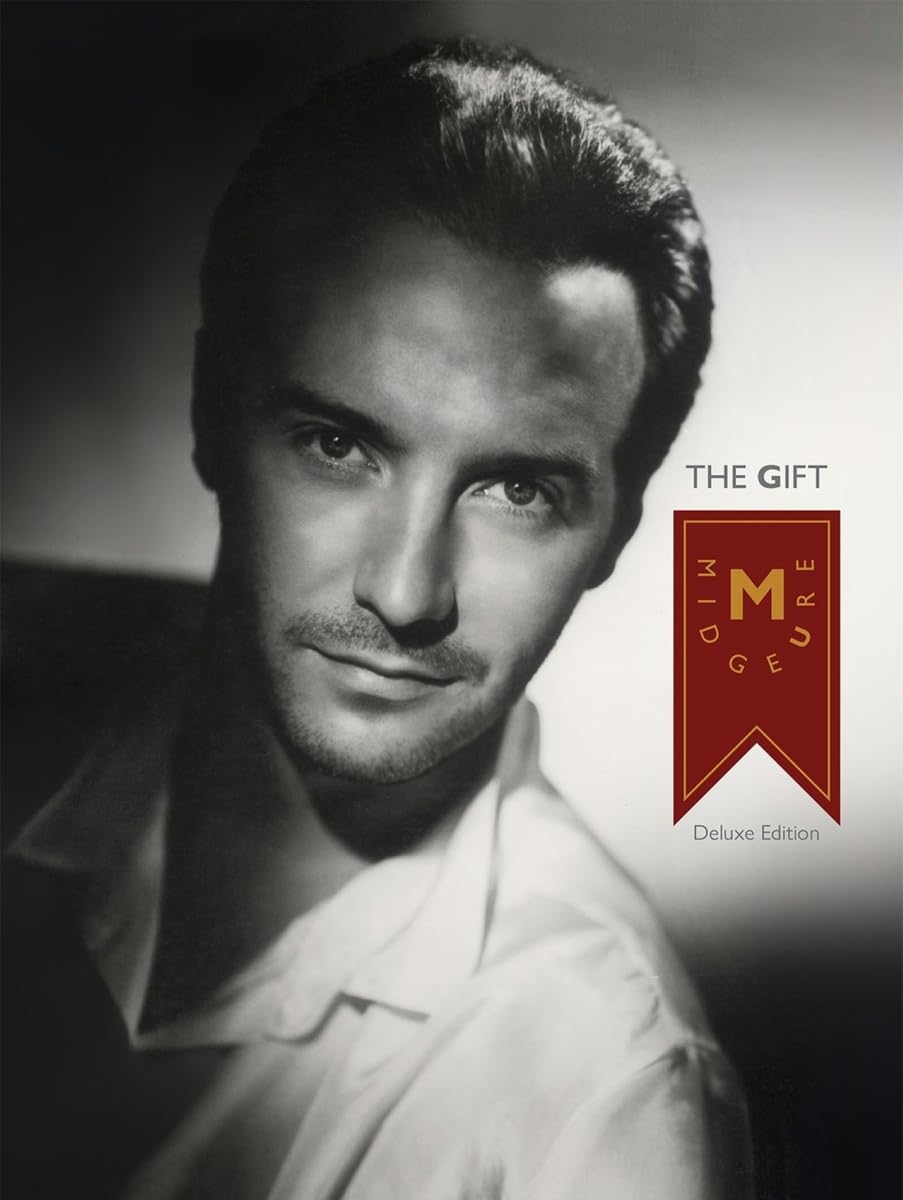

Fair enough! What about a new solo album? It’s been five years since Orchestrated.

I’ve just finished making an instrumental album, which I’ve always wanted to do. Lockdown was the perfect opportunity to do that. It’s not easier than making a vocal album, it’s just putting on a different hat. A regular album is song driven, but with instrumentals you get to concentrate more on textures. It’s textures that tell a story when there aren’t any lyrics to enhance it, so you have to get those textures right. Nearly every album I’ve made has an instrumental on, but this is the first complete collection of that sort of track and it’s been a lovely process.

Is there an overall story to the album?

Not really. One track is a melody I’d sing to my kids when they were born. I’ve finally thought: “Let’s put something down based on this little lullaby.” The album goes from that to fairly dark, ambient atmospherics. It’s a collection of thoughts and ideas I’ve had while I was static and unable to tour, sat looking across the rolling hills of Somerset and watching its different landscapes.

Will a more regular vocal album follow?

I’ve been working on one for four or five years. I’ve got so much music for it, that I’ve worked on with Ty Unwin, who produced and arranged Orchestrated. We got on really well then, and I thought it’d be nice to have a sidekick to bounce ideas off. We’ve worked remotely on it for the past couple of years, chucking songs back and forth like musical ping-pong.

I heard that Bryan Ferry takes so long that he ended up ditching everything and starting again

Midge Ure

I haven’t got into the zone of turning those ideas into completed songs. It’s easy to fall into a dangerous trap of never having a cut-off point and it goes on for so long that you go off the songs because they’ve been around for such a long time. I heard that Bryan Ferry takes so long that he ended up ditching everything and starting again, and it was maybe the same for Scott Walker. I have to be careful I don’t scrap it all and start again.

Everyone has a recording facility now, on our phones or laptops. That means you’re not thinking: “We’re in the studio and have to leave by this date.” That can be a luxury, and it can be a hindrance. If you don’t have that cut-off date, everything takes as long it takes.

There’s no longterm plan for my music now. No-one is banging at my door saying: “We need the album done by next week!” Management aren’t screaming in my ear: “The bank account has gone all funny!” You take your own time, because realistically you’re the only one who has to live with it for the rest of your life. I don’t want my kids to think in 50 years’ time: “God, he really rushed that one.”

You’re about to go on tour, for a run of dates that got cancelled twice during lockdown. How do you feel about finally getting to play these gigs?

It’s hard to express what it’s like. I had something that I’d taken for granted my whole life taken away from me, and that was really weird. Such a major part of my life was just gone. Seeing nothing in my diary for a year, that was hard.

The rehearsals with Band Electronica sound stonkingly good, and I’m really looking forward to going back out there. But it’ll be a weird tour because, after the cancellations, we’re finally playing again, but at the worst possible fiscal time. I’m going to end up paying for this tour, because production prices have gone up since 2019 and nobody is buying tickets. I totally understand why: if you’ve the choice between heating and eating or tickets for a show, that’s not a difficult decision.

It’s going to be odd, but that doesn’t detract from the joy of being back out playing again. I did seven weeks in America opening for Howard Jones, as a taste of getting back in the swing of it. After three shows on the trot, I was petrified I’d lose my voice. I hadn’t sung on stage in two-and-a-half years, and on stage there’s a lot of shouting and hitting high notes. My voice felt like it had gone and it might not come back. So that was difficult but, after those seven weeks, it gave me the belief that, yes, I can still do this. I’m determined to finally play these shows and give people a good time.

Thanks to Midge Ure, who was talking to John Earls for SDE. Ultravox’s Rage In Eden is reissued today on Chrysalis, as a 5CD+1DVD boxset, or 4LP and 2LP vinyl editions. Midge’s solo tour runs in the UK from today until September 27 and then April 24-May 31, with European shows in between.\

Compare prices and pre-order

Ultravox

Rage in Eden 5CD+DVD super deluxe

Compare prices and pre-order

Ultravox

Rage in Eden 4LP vinyl box set

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Interview

Interview

By John Earls

58