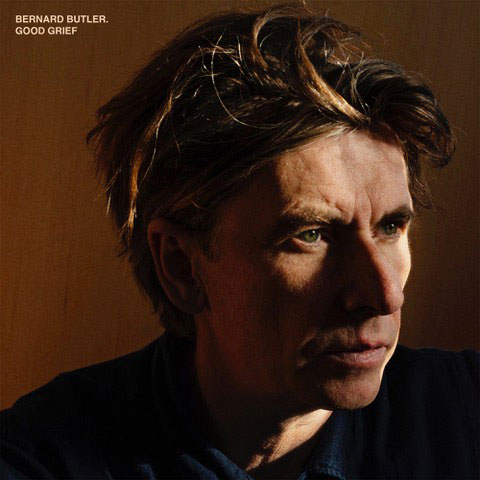

“A moving song cycle and an intimate glimpse into an interior world we’ve never gotten to see so clearly before”

Like one of his heroes, Johnny Marr, Bernard Butler has spent most of his career in almost ceaseless collaboration, lending his ideas and virtuosity to other people’s voices and other people’s songs and polishing them until they shone. With Suede that lit fireworks the afterglow of which still haven’t quite faded from the sky; then there was the gorgeous tumble of epic soul-rock he created with David McAlmont and the retro hit-making he did with Duffy. There was producing The Libertines’ two best singles. There was the barnstorming glam pop record he made with Catherine Anne Davies a few years back, and of course, there was his beautiful, Mercury-nominated collaboration with Jessie Buckley.

Unlike Marr, though, Butler has never felt comfortable settling into a solo career. Whereas the former has found a voice that suits him and made a run of decent rock records in the process, Butler has only occasionally let his name be the main draw. On 1998’s People Move On, he glued introspection and uncertainty to the type of cinematic epics he’d been making with McAlmont, then followed it up with Friends and Lovers just a year later, stripping back some of his musical excesses and finding a Stonesy-groove. And then… back to the collaborations. The solo expedition ended. Nothing. For 25 years. It always felt like a shame — both records were good. In places, People Move On is very, very good, especially on the almost preposterously, desperately stirring, ‘Stay’. And yet, there was also a feeling that Butler wasn’t comfortable. That this wasn’t really “him”. And if you can’t feel like yourself on your solo albums, when can you?

Now, after a quarter-century away from solo recording, Butler is finally back with his third album, Good Grief, a quiet, nine-song rumination on love and, especially, loss. On first listen it’s the transformation of those weary years that hits you — If you didn’t know this was the same artist, you wouldn’t have guessed it. His singing voice, previously pleasant but nondescript, has changed almost beyond recognition. In his place is a rueful veteran, his voice aged into a rich, sometimes gruff and soulful instrument, surveying decades of that aforementioned love and loss. He sounds… wise. It’s a lived-in voice. There’s a bit of Paul Weller there (Weller’s later solo career comes to mind a lot on Good Grief). A bit of, no, really, Rod Stewart and Chris Rea. Occasionally, it can sound a little mannered, but for the most part it feels like an authentic expression, weathered and warmed by time and, of course, that titular grief.

‘Camber Sands’ sets the tone, its worn, retro-rock groove spiced with bursts of bright, 70s-Elvis horns. The sonics conjure images of 70s childhood seaside holidays, all “bare shoulders” and “carefree”. But nostalgia is a double-edged sword. “I’ll bore you to tears about the good old days,” Butler sighs, balancing precariously between fond reminiscence and weary self-awareness. That’s the album’s central tension, right there. Good Grief (the jury is out on the punning title, by the way) is a reckoning with the past, both personal and musical. Here his nostalgia is nicotine-yellow and cracked where it could, in lesser hands, be a sepia photoshop filter.

The songs, Butler says, poured out of him, almost unfiltered, with decades of bottled-up feeling. You can hear that catharsis happening in real-time. That lack of filter sometimes pays off with narratives and words that are direct, yearning and plaintive — “And the silver that glistened every holiday”, he sings. “The sand mirrored the water and the water the sand/ The sea walls in the distance and Camber Sands.” It’s probably the most beautifully anyone has ever sung about a fairly bleak seaside commuter town. Sometimes, though, there’s a sense that maybe a filter of some sort might have done some good, that sometimes the first thought isn’t the best thought. “My dearest friend/I hold so tight”, he sings on ‘London Snow’, before reaching for a rhyme and coming up with “I feel for you baby/I feel your plight”. Another draft wouldn’t have hurt.

There’s a clear sonic lineage here with Butler’s past. The laid-back, loose ‘Pretty D’ could easily be mid-90s McAlmont & Butler, while ‘Clean’ could have sat as one of People Move On’s less densely layered moments. However, there’s also a sense of deliberately holding back. Butler has always understood production dynamics, when to rise and when to fall (and often, he’s preferred to rise and rise until the swell of the strings knocks the roof off), and there’s plenty of texture and shifting moods here. It never takes off in the way Butler’s stuff often does, however. You can almost hear a version of ‘Pretty D’ or ‘The Forty Foot’ that explodes into huge, soaring choruses, but here they’re held tight, wings clipped. It’s a decision only the older Bernard Butler could have made and it largely works, even if it means he won’t be syncing with the goal highlights on Match of the Day any time soon. ‘The Forty Foot’ might even be the highlight, full of shivering strings playing off guitar feedback to create the tension and release Butler used to do with explosive choruses and orchestras. It’s really something.

The 70s seem to haunt the music here much as they also haunt the lyrics, whether in the scuzzy noir of ‘The Forty Foot’ or the smoky, hungover ‘London Snow’ with its great, bluesy guitar solo. There are flashes of Americana twang on ‘Living The Dream’, blue-eyed soul on ‘Deep Emotions’, even a weary, Faces-style barroom ballad in closer, ‘The Wind’. Butler’s always had a knack for synthesising his influences into something fresh, and that skill remains undimmed.

That said, the tempos can feel a little overly uniform — the surfaces are still and glassy, even when there’s a pulling current swirling beneath. Butler’s finally allowing himself to feel these uncomfortable emotions after decades of denial and letting himself reflect, and that’s all very admirable, but a primal howl of one sort or another wouldn’t go amiss.

Even so, this is a moving song cycle and an intimate glimpse into an interior world we’ve never gotten to see so clearly before. Butler proves himself to be an exceptionally sharp-eyed observer of his own psyche, turning over memories like faded photographs, his ruminations on love, grief, aging and identity as poetic as they are plain-spoken. He’s embraced his autumnal phase, and the results are bittersweet and always worth the journey.

Butler’s return to his own voice manifests best as a celebration of the grace and grit of endurance, the hard-fought dignity of survival. “All we have is a window of time before the match burns out,” he sings on the closing ‘The Wing’. He’s made the most of his moment. The flame still flickers. The songs still speak.

Good Grief was reviewed by Marc Burrows for SDE. It’s out now.

Compare prices and pre-order

BERNARD BUTLER

Good Grief - black vinyl LP

Compare prices and pre-order

BERNARD BUTLER

Good Grief - CD edition

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tracklisting

Good Grief Bernard Butler /

-

-

- Camber Sands

- Deep Emotions

- Living The Dream

- Preaching To The Choir

- Pretty D

- The Forty Foot

- London Snow

- Clean

- The Wind

-